Political identification is a tricky game, especially out on the left. Uniquely positioned in American political and intellectual life, Harvard has its own long and complex history with communism—and its own formative experiences of anxiety and exclusion.

In February 1950, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy launched the Communist witch hunt that defined an era and established his name. “Today,” he said, “we are engaged in a final, all-out battle between communistic atheism and Christianity. The modern champions of communism have selected this as the time. And, ladies and gentlemen, the chips are down, they are truly down.”

Harvard found itself at the center in this national scare. It was a clear target, in fact, with a reputation for turning out liberal graduates and an apparently strong Communist presence between the wars—all of which had earned it the moniker “Kremlin on the Charles.” Yet throughout the many turns of the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, Harvard fought to balance its commitment to intellectual freedom with its desire to avoid being marginalized or pressured from above.

The discussion of communism on campus, initially private to Harvard’s students and faculty, became a deeply public matter, and the tensions of the ’50s left a legacy of partisanship and pariahdom that was influential through the Vietnam era and beyond.

“REDS OF ALL SHADES”

The Communist fever that made Harvard the “Kremlin on the Charles” during the 1930s was slow to take shape. In the early days of American communism, its supporters faced little criticism at Harvard.

Leftist political thought first took official form on campus in 1908 with the formation of Harvard’s chapter of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society (ISS), a national organization of student and faculty working to spread socialist thought throughout the country.

Until at least 1920, Harvard delegates went to the annual ISS Convention, where they met with students from ISS chapters at other universities to discuss contemporary political affairs. In 1914, the Harvard ISS boasted 60 members: a small fraction of the College’s enrollment, but a recognized and tolerated group.

While the 1930s are generally considered the high point of Communist activity on college campuses, the start of that decade was quiet in terms of Harvard’s campus sentiment. But if Marx was not on everyone’s mind just yet, then politics certainly were.

An op-ed in The Crimson from April 1930 affirmed a strong belief in the freedom of speech and thought on campus. The article expressed “shock” in response to the University of Washington’s suppression of on-campus Communist groups.

The author went on to give a casual overview of left-wing politics at Harvard: “Harvard has her share of reds of all shades from a pinkish tint to a dark blood-red and Harvard is rather fond of them in a very mild sort of way. They add to the variety of the college scene.”

While these tinges of red were present—and non-threatening, according to the writer—it was not until two years later that they were officially recognized. In April 1932, Harvard students participated in the creation of the New England branch of the National Student League (NSL), which became known for its strong communist ideology. Gathered in a corner of Eliot House, students from Harvard, Radcliffe, Tufts, Boston University, and other local universities established the organization.

The NSL made its political goals apparent from the start and outlined them in its official agenda, “The Student Review.” It took a clear anti-capitalist stance, seeking to “expose the sham of ‘democracy’” and fight the “consistent denial of the elementary rights of free speech, press and peaceful assembly” it perceived as prevalent in America.

Philip G. Altbach writes in his book “Student Politics in America” that the NSL provided “a key means of recruiting students to the Communist party in the early thirties.” The 1935 founding of the American Student Union dissolved the individuality of the NSL, but Altbach insists that its basic political approach remained influential in the student movement throughout the 30s and, in various forms, until the present.

Marxist thought quickly spread across college campuses around this time, according to Harvey E. Klehr, a professor of history and politics at Emory University and an authority on the American communist movement. “The ’30s was the period in which the Communist Party made its most significant intrusion into college life and attracted the most support it ever would have among college students,” Klehr said.

A SPECTACLE

In the slump of the Great Depression, a group of students met in Leverett House D-41 and formed an association dedicated to the study of “scientific Marxism.” The John Reed Club, as it was named, was strictly intellectual.

The Young Communist League (YCL), also born in the 1930s, was far more active in the promotion of communism. The YCL was steadfast in the promotion of its ideas and stubborn in the protection of its members’ identities. As recorded in The Crimson, the YCL instigated a series of anti-war demonstrations and yearly riots at the University: “They held mass meetings, parades, soap-box harangues, and released doves of peace from the steps of Widener.” The YCL preached peace above all else, but it nonetheless found itself targeted by many anti-Communists.

The organization also produced a monthly publication, “The Harvard Communist.” By this time, the Red Scare had arrived at Harvard, and students took precautions accordingly. All articles that appeared in the issues were signed by generic figures named “Max” or “John,” and all letters to the editor were addressed “Dear Comrade.” The YCL even took care to send the publication from an anonymous post office box in Boston.

Sentiment among its writers was strong. An anonymous writer in the Dec. 1936 issue wrote, “The Harvard tradition, I believe, resides not in The Crimson and not in the select clubs and not in the Board of Overseers and not in its imposing plant and not in its dear ivy-clad walls but in its radical student movement, the radical student movement and its allies among the faculty.” The magazine’s motto was “Truth is Revolutionary.”

Perhaps one of the biggest clashes between the right and the left on campus was the peace strike on April 13, 1934. YCL students cut their 11 a.m. classes in order to congregate on the steps of Widener to promote peace. In retaliation, on the same day, at the same time, and at the same place, the conservative editors of The Crimson called a meeting of the Michael Mullins Chowder and Marching Society of Upper Plympton Street—a pro-war student group.

A stand-off ensued, and the peace strike was anything but peaceful. The YCL established its place on the steps, beating a peace drum. Armed with pro-war banners, 300 Society members approached the YCL strikers (their three leaders came dressed as Hitler, Karl Marx, and a boy scout). The chaos began, and the crowd threw eggs, onions, and pennies at the YCL, who continued to beat their drum.

The YCL did not survive this farce, but other activist groups stepped in to take their place. Although still controversial, communism held a steady position on campus throughout the 1930s. The war would change all that. Many Americans had believed that the USSR would stand against Nazi Germany; this perception, however, was shattered in Aug. 1939 when news broke of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact. Suddenly, Communist allegiance was associated with Nazism and America’s wartime enemies.

By the end of the ’40s, only a small contingent of self-identified Communists remained on campus. The John Reed Club functioned as the main Marxist organization at the College, though it never boasted more than 50 members. Despite its small size, the organization still drew attention, provoking the intellectual curiosity of the College at large. On several occasions, the society invited German politician and suspected communist Gerhard Eisler to speak. Nearly 500 students attended his 1949 lecture, “The Marxist Theory of Social Change,” and many more were turned away due to capacity restrictions.

In an interview with The Crimson in 1949, then-President of the John Reed Club Robert N. Bellah ’48 noted that the club faced opposition from the University, although there was no direct threat to the organization by the administration. “There was quite a bit of pressure on us not to invite speakers who would embarrass the University,” Bellah said.

Aggression towards self-identified Communists did occasionally manifest itself. Another president of the John Reed Club, George W. Stocking ’49, was attacked by three unidentified men while promoting a Communist event in November 1948.

Despite its prior prominence, the group eventually succumbed to the negativity directed at the Communist Party. By the early 1950s, with the clouds of McCarthyism looming, the John Reed Club became drastically less visible. Indeed, in 1950, the society gave up its charter, ceasing to be officially recognized as a University student group.

There were few pro-Soviet campaigners who were active at the University after the war, and few public displays like those of the YCL. In 1948, the American Youth for Democracy, an organization with strong Communist influences, circulated its charter; some of its members were assaulted by students when distributing literature in the Yard. Under the constant threat of heckling or attack, the AYD folded and the University was left without an openly Communist student organization.

“HOTBED OF COMMUNISM”

According to Crimson archives, in Jan. 1948 The Chicago Tribune named Harvard a “hotbed of communism,” an attack leveled against the University since the 1930s. In truth, the student body was, at that point, far more moderate than it had previously been. Yet this was the time that external accusations began and the University administrators became involved.

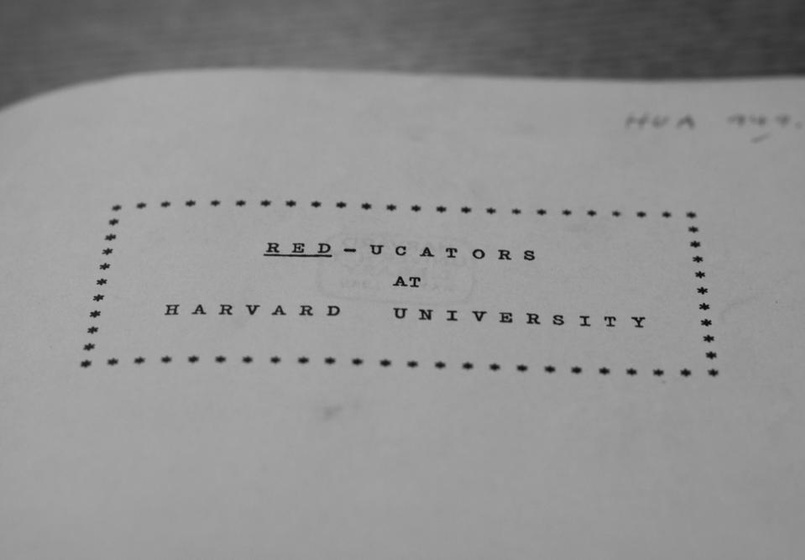

A booklet titled “Red-ucators at Harvard University,” published in 1949, accused 68 faculty members of being Communists or Communist sympathizers, once again raising questions of Harvard’s commitment to anti-communism.

Whether they were true or not, accusations that Harvard students and faculty were sympathetic to communism were not without consequence. Harvard found itself squarely in the line of fire of Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and his followers, in the uncomfortable position of trying to prove itself adequately anti-Communist without compromising academic freedom.

In 1949, the Harvard faculty voted in favor of the proposition that “‘Communists should not be employed as teachers because membership in the [Communist Party] meant that they had surrendered their intellectual integrity.”

The vote exacerbated fears that Harvard would sacrifice academic and intellectual freedom at the University in order to save face. Bolstering this rejection of communism was a statement released by Harvard President James B. Conant ’14 in June 1949 asserting that Communists were not fit to teach at the University, assuring their freedom of thought was clearly compromised.

Despite the faculty and administration’s disavowal of Communist professors, Harvard remained a target. A special congressional committee was set up in Boston to begin questioning various Harvard professors about their involvement with the Communist Party. McCarthy himself said the following of Harvard: “I cannot conceive of anyone sending their children anywhere where they might be open to indoctrination by Communist professors.”

Harvard continued to be labeled as “pink,” or sympathetic to communism. Indeed, despite direct statements by Presidents Conant and Nathan M. Pusey ’28 that Communists were not fit to be on Harvard’s faculty, the University notably refused to fire professors who McCarthy accused of Communist allegiance.

Documents in the Harvard Archives show that then-President Pusey and Senator McCarthy communicated on several occasions in 1953 regarding Harvard’s alleged sympathies to the Communist Party. In tense exchanges between President Pusey and McCarthy, Pusey drew a line in the sand.

“Harvard is unalterably opposed to communism. It is dedicated to free inquiry by free men,” Pusey wrote in a telegram to McCarthy. “I am in full agreement with the opinion publicly stated by my predecessor and the Harvard Corporation that a member of the Communist Party is not fit to be on the Faculty because he has not the necessary independence of thought and judgment.”

Some students showed their disdain for the McCarthy investigation by organizing petitions and writing letters to The Crimson. One 1953 editorial read: “In all humility, we believe the President, the Corporation, and the students of Harvard are better able to judge whether there is a Communist on the Faculty, or whether there are other evidences of a ‘smelly mess’ than is McCarthy.”

Even while condemning Communists, the University sought to publicly protect its own from persecution. This conflict came to a head in 1953 when assistant professor Wendell H. Furry refused to incriminate himself under oath during a hearing, citing his Fifth Amendment right. In May 1953, the Harvard Corporation, the University’s central governing body, released a statement refusing to fire three faculty members accused without evidence by McCarthyites.

FBI documents uncovered by The Crimson in the early 2000s indicate that some University deans privately attempted to push accused faculty members out of Harvard, but these cases seem to be the exception rather than the rule. Even if Harvard privately put pressure on accused professors to resign, publicly the University defended its right to hire or to fire.

“WHAT ABOUT COMMUNISM?”

In the 1950s, the fear of communism was gaining traction, and the terror of Communist contagion pervaded the public sphere. As well as students, respectable left-leaning academics wanted to separate themselves very clearly from Communists and communism.

In the Harvard Depository there is a 32-page book entitled “What About Communism?”. Written at the dawn of the McCarthy era, the pamphlet attentively describes the “Communist specter.” Its author, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. ’38, is one of the most respected historians of the twentieth century.

As an associate professor in the late 1940s, Schlesinger was known for frequently writing and lecturing about the dangers of communism and the importance of supporting Europe in its postwar relief effort. In his landmark book of 1949, “The Vital Center,” Schlesinger envisaged the United States as a guard post for liberal democracy against the threats of communism and fascism.

The title page of his pamphlet is decorated with a hammer and a sickle, entwined in the style of the communist logo, only the sickle bends around to look like a question mark.

“It was a favorite communist tactic,” Schlesinger wrote, “to plant secret members on the staff, say, of an organization dedicated to some good liberal cause, and then to manipulate the organization in the Communist interest.... In the same way attempts were made to slip secret Party members into the government.”

The pamphlet was published under the banner of the Public Affairs Committee. Schlesinger lamented that all too often Americans responded to the specter of communism with anxiety, running “panic-stricken from a haunted house.” Yet he made sure to include a detailed section titled “How Do You Tell a Communist?”

A person’s attitude toward the USSR, Schlesinger wrote, must be considered in addition to his attitude toward capitalism.

“If you find a man who believed strongly in collective security until Aug. 1939, who then became an isolationist until June 1941, who then demanded a second front, and who now opposes the Marshall Plan and the North Atlantic Pact...then it is fairly safe to assume that you have found at least a reliable fellow traveler.”

Even for moderates like Schlesinger, the threat of communism hung heavy.

Professor Stanley H. Hoffmann, one of the founders of the social studies program who has taught at Harvard since 1950, remembers the lasting effects of communist anxiety on campus. Hoffmann was at Harvard for the 1950-51 school year, but left briefly for France to fulfill his compulsory military service before returning.

“I came back in ’55 and the teachers... there was really a split between left and right, which was new,” Hoffman said. “For instance, social studies had not been very political when it was formed but by the mid-’50s everything was politicized and divided.”

“I think in about ’56 there was Commencement and there was a rumor that the far left and the communists and people sympathetic to communism would try to disrupt Commencement. Nobody, by the way, had decided to do so. It was just one of those rumors,” Hoffmann explained.

“On the steps of the chapel...[liberals] were standing on the left and the conservatives were standing on the right. They didn’t look at each other. It was like two separate universities and the order was perfect. So it was rather picturesque.”

By the 1950s, the ideological threat of communism, often portrayed as a plague, had become an issue that divided the University.

The transformation from tolerance to scorn in campus politics paved the way for the tumult of the ’60s and the energy of radical movements that followed. And, for those on the left, the widespread suspicion of dangerous ideas continues to influence the language and the practice of political expression.

This article has been modified to reflect the following correction:

CORRECTION: Feb. 22

An earlier version of this article misrepresented the political views of William P. Whitham ’14. Whitham does not consider himself “left-wing progressive.”