Dizzying, humorous, and sincere, “Song of A Convalescent Ayn Rand Giving Thanks to the Godhead (In the Lydian Mode)” deftly combines Ayn Rand, Beethoven, migraines, and a multitude of other elements, including a night at a strip club and a lecture at the Cato Institute. The play, which runs Oct. 15-Oct. 23 on the American Repertory Theater’s OBERON stage, presents two major questions: What does the novelist Ayn Rand say about pain, and what is the point of suffering?

The play’s title is adapted from Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132 “Heiliger Dankgesang,” or “A Convalescent’s Holy Song of Thanksgiving to the Divinity, in the Lydian Mode.” Written by Beethoven during an intense bout of illness, the composition, according to the play’s author and primary actor Michael Yates Crowley, symbolizes how pain inspires art. Crowley takes this belief and adds the Objectivist philosophies of Rand to form the foundation of “Song of a Convalescent,” a combination which lends the play a source of compelling tension and conflict.

Set up as 24 variations (or scenes), the play moves successfully between many different characters and settings. Some, such as a scene featuring Cindy McCain, are immediately comprehensible in their thematic purposes, while others are considerably more vague. It is through Crowley that the audience explores the show’s multiple worlds. In a near one-man production, Crowley plays, in total: himself; a young, angsty teenager named Garner Miller; a Professor Michael Sanders; a Doctor Schuss; the dignified drag queen Tinky Holloway; Beethoven; and, finally, a pale (and very dead) Ayn Rand. Aided by director and fellow cast member Michael Rau during transitions, Crowley moves quickly and effectively among these roles.

The play opens in present day with an introduction to the central motif, migraines, which serves as a jumping-off point for Crowley to ruminate on pain’s meaning. Throughout the production, Crowley and Rau both read from the former’s “migraine diaries,” a series of melancholic journal entries that outline the physical and psychological complications of chronic migraines. Each excerpt details a particular day’s events and the levels of of pain experienced, as well as the toll Crowley’s suffering exacted on him. These highly emotional readings powerfully manifest and reinforce the consideration of pain that lies at the play’s center.

Following scenes—Professor Sanders’ lecture on Ayn Rand at the Cato Institute and Holloway’s musical performance and musings at a strip club in Peoria, Illinois—propel the play’s narrative forward. Both characters’ unironic reverence for Rand informs much of the production’s oddball humor. During these scenes, Crowley still finds a way to maintain the migraine motif; Holloway, for instance, performs songs from her album “Migraineuse.” What Crowley lacks in musical talent—his performances are entertaining but not tuneful—he makes up for in dynamic facial expressions and effective staging. Holloway’s utter devotion to Rand and her own intellectual and musical talents make for a few memorable moments, particularly in the play’s final scene.

Experimental in nature, the play’s set design is minimal: A faded Persian rug, piano, and table where Rau controls sound and video form the basis for about 10 different settings. Creative use of video projection and audio effects establish different backgrounds, signal transitions, provide humor, and allow members of the audience to stay engaged despite the sparse set design. The level of audience participation incorporated in the play before and during the performance makes the experience dynamic. Audience members are asked to write on note cards something that causes pain; these note cards are eventually read out loud by Rau as “Things Ayn Rand Does Not Care About,” creating an enjoyable, improvisational moment.

Crowley does an admirable job at juggling so many roles, yet unfortunately not all of them are entirely distinct or particularly remarkable. His rendition of Beethoven, full of interjecting “ja’s” in an overperformed German accent, treads into caricature and feels forced. Additionally (and strangely), Rand’s cultured demeanor comes across as too similar in personality to the intellectual Holloway. Crowley does a much better job with other characters; the nutty migraine specialist Doctor Schuss, for example, is thoroughly entertaining, providing memorable lines such as “Castration is beautiful, really, like a great game of tennis,” which Crowley delivers in a cheerily nonchalant manner. Rau, the only other actor in the show, who takes over the stage during Crowley’s switches between characters, has a laidback style that meshes well with Crowley’s dramatic monologues. He executes vocal and physical humor quite well throughout the performance, earning many laughs.

A couple of weaknesses—fumbles in dialogue, one scene with strobing lights and random flashing images that feels gratuitous—detract only slightly from the play’s overall success. “Song of a Convalescent” works best when it strikes a balance between humor and sincerity, moments exemplified by Holloway’s enthusiastic musical performances. Although it seems haphazard at its surface, the play maintains a sense of narrative control through the repetition of Crowley’s migraine diaries.

The play’s closing scenes provide satisfying emotional and intellectual resolutions. A line from the penultimate variation, a monologue from Crowley, gives a heartfelt and moving answer to the question of suffering’s purpose: “Pain is the most objective experience we have.” “Song of a Convalescent,” while never afraid to make light of difficult situations, nevertheless insists on an unflinching empathy with suffering and in doing so raises tough questions about courage, perseverance, and meaning.

Read more in Arts

'The Importance of Being Earnest' Brings Wilde to BrooklynRecommended Articles

-

Other Schools Face Same ProblemsFor some Harvard users, it is hard to imagine how the new financial information system could possibly be worse. But

-

CRITICS IN THE BACKCOURTTo the Editors of The Crimson: Hating myself for doing this, as losers gain no honor in verbal warfare post

-

JUNIORS WON CLASS GAMESThe Juniors won the interclass track games held in the Stadium yesterday afternoon with a total of 50 2-3 points.

-

Candy Crowley Receives Journalism Career AwardNews anchor Candy A. Crowley was awarded the Goldsmith Career Award for Excellence in Journalism during a ceremony at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum on Thursday evening.

-

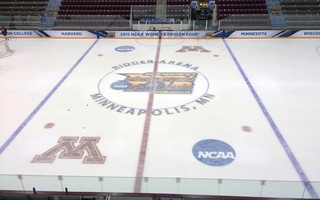

Overheard in Minneapolis: Women's Ice Hockey's Frozen Four Press Conference

Overheard in Minneapolis: Women's Ice Hockey's Frozen Four Press Conference