UPDATED: Dec. 18, 2012, at 8:08 p.m.

When Apple co-founder Steve Jobs died last year, Cantabrigians gathered on Main Street in Kendall Square to mourn the passing of a tech industry god.

They stood near Jobs’ plaque on the Entrepreneurial Walk of Fame, where they laid flowers on the star bearing his name. The Entrepreneurial Walk of Fame had opened that year to honor and celebrate big names in business, and Kendall now seemed a place to go to honor an innovator.

“We want to be the head of innovation and entrepreneurship—what Wall Street has for finance and what Hollywood has for celebrities,” said Travis McCready, executive director of the Kendall Square Association, a board of community stakeholders.

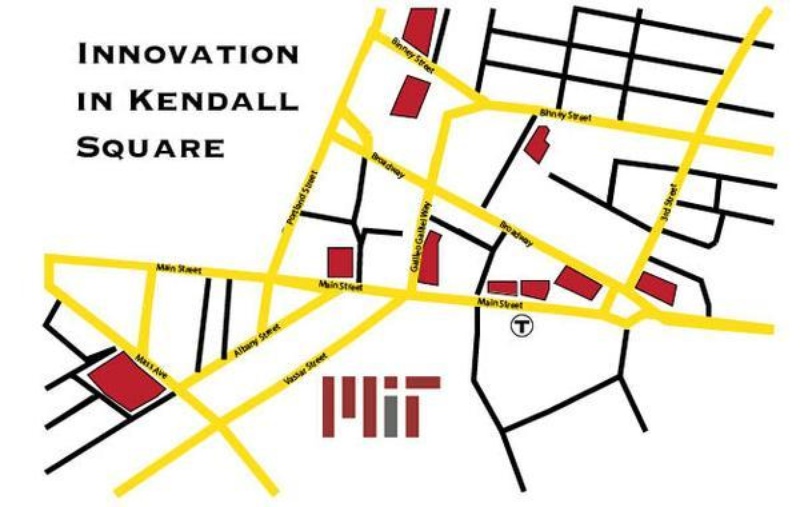

Since its bygone days as a home to manufacturing factories, Kendall Square has become a magnet for the global information technology, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical industries, drawing companies like Google, Microsoft, and Pfizer. Also home to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, it has been called the most innovative square mile on Earth by the Boston Consulting Group.

Once a post-industrial wasteland, the now-vibrant Kendall area could provide a model for Harvard as it reboots plans to transform the underdeveloped Allston neighborhood just across the Charles River into the University’s research hub.

WASTELAND TO WONDERLAND

Fifty years ago, Kendall Square—today a key driver of Cambridge’s economy—was empty.

Manufacturing companies had moved out to make room for NASA’s new Electronic Research Center, which was expected to reinvigorate Kendall Square, according to Charles M. Sullivan of the Cambridge Historical Commission.

But President Lyndon B. Johnson thwarted this dream of revival, deciding instead to locate NASA’s new facilities in his home state of Texas.

The ensuing decades were sleepy ones for Kendall. But the construction of several office buildings in the 1990s at last triggered an explosion of development that has continued to this day.

Jeff Lockwood, the global head of communications at Novartis, explained the pharmaceutical company’s decision to open a new global headquarters for research operations there: “We wanted to come and grow in Cambridge. This is where science is today and where science is going to be tomorrow.”

Google followed in Novartis’s footsteps, arriving in Kendall Square in 2006.

These large companies attracted new start-ups, like GnuBIO, a DNA sequencing company co-founded by Harvard physics professor David A. Weitz in 2009.

“It’s the DNA of the Square, the aura. There’s so much going on,” Weitz said, explaining Kendall’s thriving innovation community.

As big-name companies and fledgling start-ups have made their homes in Kendall Square, the district has adapted to meet the needs of the new arrivals. In just the past three years, 20 restaurants have opened in Kendall Square.

“Before there was one decent restaurant, Legal Sea Foods. We all ate there way too many times,” said Tim Rowe, co-founder of the Cambridge Innovation Center, an office space that caters to start-ups.

“It was certainly not a vibrant area before. You had to have a reason to go there,” said Jeremiah P. Murphy Jr. ’73, the president of the Coop, which has a branch in Kendall Square.

“SYNERGETIC”

Kendall Square’s booming science and tech industry has been a boon for MIT, which has courted several of these companies through various types of partnerships.

“What we’ve found is proximity is one of the key accelerators in science. We’re all right here,” said Sarah E. Gallop, co-director of government and community relations at MIT.

MIT has formed partnerships with companies including Novartis and Pfizer. Currently, MIT is building a facility for Pfizer, which will be located across the street from the school’s brain and cognitive science department.

For the most part, however, MIT has kept its distance from much of Kendall Square’s development.

The school has been a beneficiary rather than a driver of the area’s growth. Gallop said MIT had little responsibility for the growth of Kendall Square. “Our involvement was synergetic,” she said.

Harvard hopes to enter similar relationships with tech companies and businesses in Allston—a strategy known as co-development.

“Allston’s growing academic community will both benefit from and contribute to the neighborhood, promoting activity in the area and attracting new businesses and industries to Allston and greater Boston,” University Provost Alan M. Garber ’76 put it in an interview with The Crimson in May.

Harvard’s expansion strategy diverges from MIT’s, however.

“The classical difference between Harvard and MIT is Harvard acquires land for institutional use,” said McCready, who was formerly Harvard’s director of Cambridge community relations.

THE KENDALL BLUEPRINT

In some ways, the initial phases of Harvard’s Allston development have already begun to mirror Kendall Square’s rise.

Kendall received a boost from the opening of the Cambridge Innovation Center in 1999.

The 160,000-square-foot facility provides resources and inexpensive office space for young entrepreneurs attracted to the area by high-profile tech and biomedical companies.

Steve Vinter, site director of Google’s Cambridge office, which previously rented space in the Cambridge Innovation Center, noted the important role the CIC played in making Kendall a hub for innovation.

“You need an incubator to attract the start-ups there and cornerstone tenants that you can build around,” Vinter said.

Founded in 2011, the Harvard Innovation Lab serves a similar purpose, striving to encourage entrepreneurship among students, faculty, and community members.

At the i-Lab, located across the street from the vacant swath of land that will one day be home to Harvard’s Allston Science Center, local entrepreneurs and University affiliates can receive support for launching their own ventures.

“We think of ourselves as a start-up within Harvard. We’re always open to new ideas,” said Gordon S. Jones, managing director of the i-Lab.

The i-Lab’s mission, however, differs from the CIC’s. Rowe, the co-founder and CEO of the Kendall incubator, said the companies at the CIC tend to be in more advanced stages of development than those at the i-Lab.

Allston has yet to attract big-name companies like those in Kendall. But the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences may relocate there, which could add an incentive for biotech businesses to establish a presence in Allston.

And the working-class Allston neighborhood has received financial backing from one of the industry giants located in Kendall Square. In 2011, Google—which according to Vinter has no plans to move out of Kendall Square—invested almost $30 million in the new Charlesview Apartment Complex, a construction project whose completion is key to the University’s plans for Allston. The new complex will free up the current complex’s land, which abuts the Business School.

The realization of Harvard’s dreams for Allston may be hindered by the fact that the area faces transporation issues Kendall Square did not. While Kendall benefits from its stop on the MBTA Red Line, Allston is only accessible by bus.

Sullivan pointed out some of the difficulties Harvard’s Allston hub will have to overcome: “Housing, transportation, and scientists all being in close proximity to one another—none of those things are present in Allston right now.”

Allston’s future as a center for science and innovation remains distant. After halting construction due to financial constraints in 2009, the University has just restarted planning in the past year. In July, Harvard announced that it will relaunch construction in 2014.

Kendall Square’s evolution is just one model that Allston might mimic.

“[Allston] will have its own character,” McCready said, “but no one knows what that is.”

—Staff writer Kerry M. Flynn can be reached at kflynn@college.harvard.edu.

Read more in News

For Creative Concentrators, A New Happily Ever After