After diagnosing Nowinski with post-concussion syndrome, Cantu explained that concussions were a serious biological problem and helped Nowinski realize that he needed to reframe the discussion in order for the sports world to better understand the repercussions of head injuries.

“When I started intensively researching the issue, I realized that the research that told us that we should change sports was out there, but wasn’t in an easily digestible structure,” Nowinski says. “I figured that putting it together into a persuasive argument was step one ... I didn’t know what steps would follow but I knew the research needed to be compiled in a way that people could sit down with it for a couple hours and walk away understanding it.”

Nowinski decided to put his ideas in writing. By the summer of 2005, his 200-page manuscript, “Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis from the NFL to Youth Leagues,” was finished.

With the help of Alan Schwarz, at the time a freelance sportswriter writer for the New York Times, he got in touch with publishers.

“I thought his manuscript was great,” says Schwarz, who had written one book on baseball statistics and was working on another.

Nowinski’s book—in which he called out the NFL for its “tobacco-industry-like refusal to acknowledge the depths of the problem”—was published to positive reviews in October 2006. A month later, its research was tragically validated, when former Philadelphia Eagles defensive back Andre Waters committed suicide in his Tampa Bay home.

Nowinski read about the death, and realized that something was strange—Waters was known to be one of the hardest-hitting players in the league during his playing days, but was also widely considered to be a gregarious, happy individual. His decision to kill himself was a mystery Nowinski wanted to solve, and a brief Internet search led Nowinski to discover that Waters had once told a reporter that he had suffered at least 15 concussions during his playing days. Nowinski decided to initiate an inquiry into Waters’ suicide.

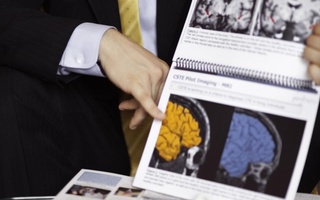

He received permission from the player’s family to have Waters’ brain tissue examined, and sent samples of the tissue to neuropathologist Dr. Bennet Omalu at the University of Pittsburgh. Nowinski wanted them checked for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the tangled threads of irregular proteins that cause degenerative disease and have been linked to cognitive and intellectual dysfunction, including depression.

Omalu’s findings confirmed Nowinski’s predictions. Waters had suffered from depression caused by sustained brain damage that he had accumulated while playing football. Omalu found that Waters’ brain was comparable to that of an 85-year-old man suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

Shortly after, Schwarz heard from Nowinski, who was then still working in Boston as a pharmaceutical consultant.

“He called me and said ‘Alan, I think I have something pretty big here, and you’re the only one who ever took me seriously,’” Schwarz says. “And so he told me about the Andre Waters story.”

Schwarz jumped at the lead, and an article that linked Waters’ depression to head injury—still a novel idea at the time—was published in The Times in January 2007. A month later, HBO Real Sports reached out to Nowinski, asking him to participate in three separate features that told the story of the concussion crisis.

“It was amazing how many leaders in the sports world watched that show,” Nowinski says.

Knowledge was beginning to spread about the detrimental impact that brain injury could have. In the spring of that year, Nowinski received a call from Julian Bailes, the chairman of the department of neurosurgery at West Virginia University and a former Pittsburgh Steelers neurosurgeon, who explained that there were similarities between the Waters case and the death of former Steelers offensive lineman Justin Strzelczyk, who had killed himself by driving 90 miles per hour against the flow of traffic to evade police.

An autopsy revealed that Strzelczyk had not been intoxicated—as was initially believed—but was rather suffering from brain damage that had led him to act in a manner many assumed was bipolar. Nowinski contacted Omalu about conducting a post-mortem examination of Strzelcyk’s brain, in which Omalu again found signs of CTE.

Read more in Sports

TEAM OF THE YEAR RUNNER-UP: Crimson Dominates Nation’s BestRecommended Articles

-

Ivy League Leads Trend in Concussion PreventionThe winds of change howling through the world of sports safety have become impossible to ignore. Traditional football has nearly been toppled by the gusts, and the winds’ next victim, hockey, lies just around the corner. Adding to the drafts is none other than our little Ivy League. The breezes began back in 2009, when the NFL was called out by Congress for not adequately protecting its players from the dangers of concussions and other head injuries.

-

Who You Should Root for in the NFL PlayoffsHome team knocked out of the playoffs? Still reeling from Fitzpatrick’s fourth place AFC East finish? The Back Page has ...

-

Concussed: Down and Out

Concussed: Down and Out -

Panelists Discuss Head Trauma ResearchThree panelists described current medical research and long-term goals to reform care and policy on athletic head trauma and concussions during a biannual symposium of the Harvard Society for Mind, Brain, and Behavior in Science Center C on Friday afternoon.

-

Murphy Era of Harvard Football Turns 20Twenty years into his Harvard tenure, football coach Tim Murphy reflects on the most memorable games, seasons, and players of his career with the Crimson.

-

Professional Athletes Discuss Intersection of Sports, Tech at I-Lab

Professional Athletes Discuss Intersection of Sports, Tech at I-Lab