“That was one of the first times where I blacked out and forgot where I was and what we were doing,” Nowinski says. “I just went backstage and hid and tried to clear the cobwebs.”

The next day, his headache had almost faded, and Chris Harvard told his doctor that he felt fine. He was back in the ring an hour later.

But he had spoken too soon. Just as Bubba connected with a forearm to the back, Nowinski’s vision began to grow fuzzy again. The blood was pounding so strongly that he became afraid his head would explode. After the match, the headache was much worse, but the pain went away after an hour, and Nowinski figured he’d give it another go the next night.

He performed as such for three more weeks, but soon realized that the concussion had left his brain in terrible shape. He was suffering from severe migraines and even depression.

“I didn’t understand why I had headaches everyday, and why my short term memory had disappeared,” Nowinski says. “My parents were always worried about me. I became very tough to be around, so my friends were supportive at first and then I think I became a drain on them. It wasn’t until I went to my eighth doctor that I started understanding that what was happening could be explained by biologically.”

“For a solid year he was not himself,” Kacyvenski adds. “He’s usually unbelievably charismatic, but he was a different person. He could not function at a high level both emotionally and mentally.”

A NEW BEGINNING

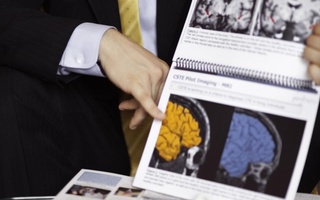

After taking an extended absence from wrestling, Nowinski decided he needed to officially retire from the WWE in 2004. He then started to investigate what was wrong with his brain, and to research the dangers of concussions and the long-term brain trauma they could lead to.

After talking to former teammates and friends, he discovered that information about the hazards of brain injury had never truly reached the sports world, and that people were dying because of it.

Something had to be done.

“Once my eyes were opened to how easy the fix was to save so many lives, I felt obligated to try and change it myself,” Nowinski says.

He began to try to spread the word about the dangers of concussions, but says he faced a world that was often skeptical about the dangers posed by sports-induced head injuries.

“So many people wanted him to stop,” Kacyvenski says. “So many powers that be wanted to push him out and squash him, but he would say ‘no.’”

HEAD GAMES

Shortly thereafter, Nowinski met doctor number eight—Robert Cantu, the Chairman of the Department of Surgery, Chief of Neurosurgery, and Director of Sports Medicine at Emerson Hospital in Boston.

Read more in Sports

TEAM OF THE YEAR RUNNER-UP: Crimson Dominates Nation’s BestRecommended Articles

-

Ivy League Leads Trend in Concussion PreventionThe winds of change howling through the world of sports safety have become impossible to ignore. Traditional football has nearly been toppled by the gusts, and the winds’ next victim, hockey, lies just around the corner. Adding to the drafts is none other than our little Ivy League. The breezes began back in 2009, when the NFL was called out by Congress for not adequately protecting its players from the dangers of concussions and other head injuries.

-

Who You Should Root for in the NFL PlayoffsHome team knocked out of the playoffs? Still reeling from Fitzpatrick’s fourth place AFC East finish? The Back Page has ...

-

Concussed: Down and Out

Concussed: Down and Out -

Panelists Discuss Head Trauma ResearchThree panelists described current medical research and long-term goals to reform care and policy on athletic head trauma and concussions during a biannual symposium of the Harvard Society for Mind, Brain, and Behavior in Science Center C on Friday afternoon.

-

Murphy Era of Harvard Football Turns 20Twenty years into his Harvard tenure, football coach Tim Murphy reflects on the most memorable games, seasons, and players of his career with the Crimson.

-

Professional Athletes Discuss Intersection of Sports, Tech at I-Lab

Professional Athletes Discuss Intersection of Sports, Tech at I-Lab