Right in the heart of East Los Angeles, at the corner of Cesar Chavez Boulevard, lies a sand-colored two-story building faced with turquoise tiling and bathed in a rainbow mosaic. In the 1980s, the building — then home to Self Help Graphics & Art — existed as a creative and mutual aid space for East L.A.’s Chicanx community and a monument to the Chicanx Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s and ’70s. There, aspiring and practicing Chicanx artists alike were encouraged to break with colonial ideologies and learn to celebrate and value their roots. Spearheaded by Franciscan nun and artist Sister Karen Boccalero, Self Help Graphics served as a home base for East L.A.’s activists, artists, poets, and punks — all of which could be seen flitting in and out of the community art studio’s cerulean doors.

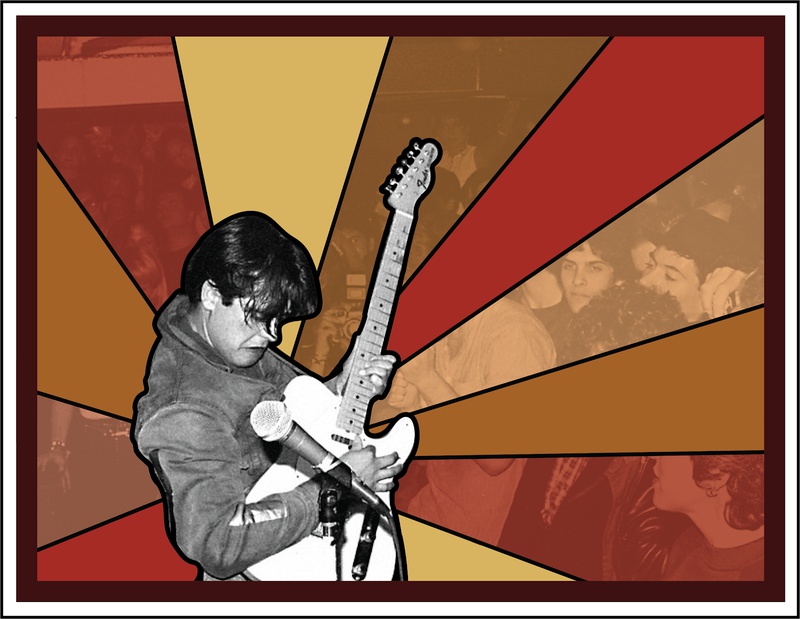

By the mid 1970s, Willie Herrón, an artist and founding member of Chicanx punk band Los Illegals, and Joe Suquett (better known as Joe Vex), joined forces with Sister Karen to found Club Vex on the top floor of the Self Help Graphics building. This all-ages punk club, set up twice a month, was created to provide East L.A.’s burgeoning Chicanx punk scene with a community performance venue and meeting hub. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, The Vex was deeply ingrained in punk legend as the place where Chicanxs and other Angelenos could go to see the musical revolutionaries at the forefront of the Chicanx punk movement — punk bands like Los Illegals — unfettered in all their rage and glory.

The East L.A. punk scene, while less popularized than its Hollywood counterpart, was significant in its representation and advancement of Chicanx identities and causes. Taking up the mantle of Los Saicos from Peru, these L.A. punk bands desired to both embrace and project their shared experience of Latinidad through music.

Los Illegals, for example, first broke into the East L.A. punk scene with their politically-charged 1981 release, “El Lay.” In the song, Herrón sings against the deportation of his stepfather, an undocumented Mexican immigrant, as civil rights activist Jesus "Xiuy" Velo’s bass drives the song into a violent frenzy of smashing cymbals and cutting lyrics. “Being illegals / we can’t all be wrong,” he shouts, his message echoing that of the Chicanx Movement. “Is this the price / You have to pay / When you come / To the U.S.A.?”

In another song, “We Don’t Need a Tan,” Herrón sings a curt warning about dangers of the American government and its treatment of fellow Chicanxs. “The federal tax man says / ‘Don’t leave us alone’ / And all those politicians wanna / They wanna swallow your home,” he sings, as drummer Bill Reyes fires away into an intense, violent rhythm.

Other bands like The Zeros, a Chicanx punk band who many dubbed the “Mexican Ramones,” explicitly used Mexican musical influences in their otherwise purely-punk songs. In “Rico Amour,” for example, the band makes use of more folkloric percussion under the heavy, sludgy riffs of guitarist Robert Lopez, later known as El Vez.

With the prominence afforded by venues like The Vex — where everyone from the Red Hot Chilli Peppers to the Chicanx band The Brat played and where Hollywood punk and East L.A. punk were able to melt into a greater punk scene — these Chicanx bands were also able to expand their influence into both existing and just emerging genres.

East L.A. punk band, The Bags, for example, are widely considered to have significantly inspired the hardcore punk movement of the 1980s. The Chicanx frontwoman, Alice Bag, would rage heavily on stage as she all-but-shrieked the lyrics to powerhouse songs like “Gluttony” and “We Don’t Need the English.” So powerful were her performances that she was nicknamed “Violence Girl” by the band’s fans and contemporaries. The band’s signature aggression lent itself directly to the punk movements to follow, establishing The Bags as luminaries in the greater punk scene, not just that of The Vex.

Chicanx punk band The Plugz, known for their innovative blend of punk mainstays and a Mexican folk sound, were also able to gain exposure far beyond the scope of Cesar Chavez Boulevard. By 1984, they had played with Bob Dylan on his inaugural The Late Show with David Letterman performance and attracted a sizable new audience that had been previously inaccessible to the Mexican American punk rockers.

The Chicanx punk movement, one rooted deeply in Latinidad, did not exist merely in the periphery of the increasingly mainstream, predominantly-white institution of punk. Instead, it both influenced and was influenced by the scene, all the while forwarding a unique legacy and providing lasting inspiration to the bands who would follow.

This past month marked my first ever time visiting L.A., which meant the historic Self Help Graphics building was a must-see. While Self Help was forced to move locations in 2007 out of economic necessity, the mosaic-sheathed building still promised to stand sparkling under the scorching L.A. sun.

Upon arriving, the venue I had only known as the vibrant centerpoint for an insurgent music scene seemed dead and desolate in comparison — a mere relic of punk mythology. (It was only later that I learned that a couple miles away, the newest iteration of Self Help Graphics was up and running in a new central-L.A. location, where it operates under the same commitment to mutual aid and community building as it did back on the corner of Cesar Chavez Boulevard.) Though buried in the past, the raw energy from the early years of The Vex still seemed to hang thick in the air like static, a reminder of what once was and what became of it.

“The most important thing that people need to know is that punk was not invented by White males, nor was it exclusively their domain,” Alice Bag said in an interview with AJ+. “Punk was created by women, people of color, and queers. And without all of us, it would be nothing.”

Indeed, without the groundbreaking musical style by iconoclastic Chicanx or Chicanx-fronted bands like The Bags, Los Illegals, and The Plugz pushing the fore of what could be accepted and listened to, the punk scene as we know it today could have been wildly different. Even beyond the United State’s borders, politically-charged punk movements like that of East L.A. — movements that were rooted in the expression and representation of Latinidad — were also inspiring punk artists in Latin America, who were starting to take up their instruments as a form of political resistance in a wave of punk that would spread throughout the ’80s and into the ’90s.

—Staff writer Sofia Andrade’s column, “Demolición: Punk and Latinidad” explores the often overlooked Latinx roots of the punk scene. You can reach her at sofia.andrade@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter at @SofiaAndrade__.