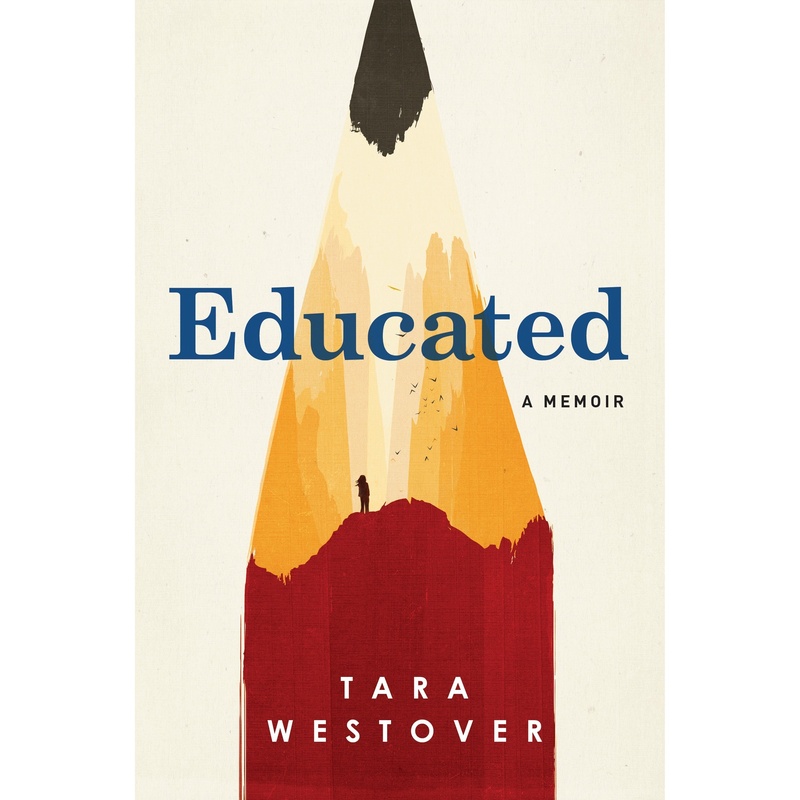

In her incredibly thought-provoking memoir, “Educated,” Tara Westover describes a life that is different from the usual American childhood experience. She “had grown up preparing for the Days of Abomination, watching for the sun to darken, for the moon to drip as if with blood,” her parents spending little time preparing Westover and her six other siblings for the world outside of their hometown in Buck’s Peak, Idaho. After years of working in a scrap yard with her father and older brothers, Westover takes the ACT that will eventually lead her to Brigham Young University, Cambridge College, and Harvard. Westover questions the doctrines her family has instilled in her since birth, the reliability of memory, and the obligations a daughter has to her family. Written with great clarity, “Educated” provides a perspective that forces readers to consider the privileges they enjoy thanks to their education.

Westover’s father is a staunch Mormon that believes the government and the “Medical Establishment”—which includes any hospital or formally trained doctors—will lead to the downfall of civilization. Her mother is an herbalist who makes home remedies, and none of the children are permitted to go to a doctor or hospital. To the average American this might seem radical, but it isn’t until Westover is an adult that she begins to rethink the ideas she was raised to believe. In college, she takes an Advil instead of a tincture for an earache and can’t “comprehend [the pain’s] absence.” But more than anything, her distrust of medical establishments makes it especially difficult for her to seek counselling even in the most stressful of times, a key issue for the second half of the memoir.

“But [her] father had taught [her] that there are not two reasonable opinions to be had on any subject: there is Truth and there are Lies.” A traditional American public education usually facilitates discussion by implementing methods like Socratic Seminars, in which a teacher asks questions that students are encouraged to think through. However, Westover was not granted such liberties in her upbringing. Instead, her mother attempted to homeschool Westover and her siblings—a task that soon fell to the wayside early on, leaving Westover with nothing more than the ability to understand basic math and reading comprehension. It is not until her late teens that she teaches herself algebra, among other skills, in order to pass the ACT. Her unfamiliarity with original thought is an obstacle Westover must overcome when she arrives at college, and the juxtaposition between Westover and her classmates highlights the privilege their education allotted them in terms of having the agency to think for oneself.

Similarly, Westover has had no exposure to basic facts of history before arriving at BYU. For example, she tries to read Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” but she “was unable to distinguish between the fictional story and the factual backdrop. Napoleon felt no more real to [her] than Jean Valjean. [She] had never heard of either.” Westover is forced to self-teach knowledge that most people take for granted and is too embarrassed to admit what she doesn’t know. She is by no means stupid, but growing up not having access to information makes her appear unintelligent to her peers. Rather than belittle Westover, these interactions highlight how people quickly judge the intelligence of others without taking into account an individual’s background and divergent levels of education.

Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects of the memoir is Westover’s admittance to memory’s unreliability. In a form that relies heavily on memories, it is important that their malleability is accounted for. Occasionally, Westover includes a footnote that explains that what she has written is what she remembers, but it differs from what each of her brothers claim happened. In other moments, Westover uses diary entries to compare how she felt directly after an intense moment to how she now views the episode. Her active introspection highlights the ability for people to change, but also forces the reader to think about how Westover’s experiences between then and now have shaped her. She also explains habitual behaviors through specific retellings. For example, instead of stating that her father believes the government has ties to the Illuminati, she recalls “one lunch in particular.” Westover chooses these moments for the strength of the statement they make, and this in turn makes her memoir more potent. Overall, her transparency about the untrustworthy nature of memories solidifies rather than undermines Westover as a storyteller.

The memoir format can easily lend itself to casual, if unintentional bragging on the author’s part: Westover received a PhD despite never stepping foot into a classroom until she attended BYU. However, this book is less a self-congratulation and more a cathartic expression of her struggles. While Westover has clearly worked hard to achieve so much, she is not afraid to tell on herself. She admits that at one point she “was so far behind in [her] work that, pausing one night to begin a new episode of “Breaking Bad,” [she] realized that [she] might fail [her] PhD.” The message is not that hard work pays off but rather that even those who work hard have difficult days. These episodes make Westover no less incredible for her successes but do make her feel more human and less larger-than-life.

Westover humbly describes her struggle with Mormonism, family relationships, abuse, and education in a memoir that questions the readers’ perception of education. It is honest, admitting to the fallibility of memory. In this truth comes strength. “Educated” is so much more than a memoir about a woman who graduated college without a formal education. It is about a woman who must learn how to learn.

—Staff writer Caroline E. Tew can be reached at caroline.tew@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @caroline_tew.

Read more in Arts

What (the Hell) Happened: Post-Trump Political Satire