UPDATED: March 30, 2015, at 1:12 a.m.

William F. Morris IV ’17 describes his hometown of Maysville, Ga., as having “more cows than people and more pickup trucks than college degrees.” The first from his high school to enroll at Harvard since 1973, Morris was excited to experience an environment completely different from his home in Georgia. Much of Morris’s life in Cambridge, however, has been characterized by Southern stereotyping on the part of his peers.

During the first week of school, Morris says, he was asked which side he would take “if the Civil War happened today.” A classmate of Morris’s, referring to his distinctive accent, once asked Morris’s friend how somebody who sounded “retarded” could have been accepted to Harvard. After he was asked how many slaves he owned at a final club punch event sophomore year, Morris left out of frustration.

“I’m vegetarian, I’m not religious, [I’m] liberal,” Morris says. “But people hear my accent and automatically think, ‘Oh, Southern Will, he’s Southern.’”

{shortcode-5372540d3c3bb25222db376d287e3a5d550ce779}

Morris credits his thick, Southern accent—which he claims has faded somewhat since freshman year—with eliciting some of the stereotyping to which he has regularly been subject to at Harvard. His Georgia flag hangs proudly from the wall of his Pforzheimer House bedroom, and Morris says Cambridge often still does not feel like home.

With an undergraduate population nearly four times the size of his hometown, Morris’s tenure at Harvard has tested him in multiple ways. Students from underrepresented areas often say the transition to Harvard comes as a culture shock both socially and academically. They report that they know very few Harvard students upon entering freshman year compared to peers from areas like Boston and New York.

While enhanced recruiting efforts and financial aid initiatives in recent years have created the most diverse student body in the school’s history, Harvard’s geographic numbers are still unrepresentative of the United States as a whole. In the Crimson’s freshman survey of the Class of 2017, fewer than 12 percent of respondents identified as coming from Georgia and the rest of the Southeast region, while 41.1 percent of students called the Northeast home. The College’s Admissions Office does not have plans to create proportioned quotas for states or geographic regions, and representatives say they engage in regular recruiting efforts to form a regionally diverse student body as part of its ongoing goal to enhance students’ experience at Harvard.

But despite those efforts, undergraduates from parts of the country that do not often send students to Harvard say that they face challenges when they arrive in Cambridge, from culture shock to trouble adjusting academically and navigating an unfamiliar social network.

Diversity—racial, ethnic, or geographic—was not often a word used to describe Harvard College during its first few centuries. In 1922, former Harvard President

Abbott Lawrence Lowell ’77 proposed a quota capping Jewish students’ enrollment at 15 percent of the class. The incoming freshman class in 1950 had just four black students, and it wasn’t until 1970 that administrators undertook “the great experiment” to eventually make the Harvard housing system co-ed.

While Harvard today is far ahead of the Harvard of years past in terms of diversity, imbalances persist in the undergraduate population with regard to students’ geographic origins. According to enrollment data from the Office of Admissions provided by Faculty of Arts and Sciences spokesperson Anna Cowenhoven, 51.5 percent of the non-international students who enrolled in Harvard’s Class of 2018 hail from just four states: New York, New Jersey, California, and Massachusetts. In contrast, those states make up only 23.2 percent of the U.S. population, according to 2014 projections—the latest available—based on the 2010 U.S. Census.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the greatest example of Harvard’s regional imbalance. Massachusetts’s 6.7 million residents constitute about 2 percent of the nation’s population, according to 2014 projections based on the 2010 Census. In contrast, 15 percent of current Harvard freshmen hail from the Bay State.

While 231 current freshmen hail from Massachusetts, Louisiana sent just two students to Harvard this past year, a small number considering its population of 4.6 million, according to 2014 Census projections. Of those two, Christopher C. Higginson ’18 attended the Groton School, an elite private boarding school in Massachusetts, while Luke Z. Tang ’18 is a graduate of Benjamin Franklin High School, one of New Orleans’s premier magnet schools.

Amongst the seven high schools that were most represented in Harvard’s Class of 2017—Boston Latin School, Phillips Academy in Andover, Stuyvesant High School, Noble and Greenough School, Phillips Exeter Academy, Trinity School in New York City, and Lexington High School—five fall in the New England region and two in New York City, according to data from the Freshman Register.

In total, 310 students in the Class of 2018 are New England natives. Though the six New England states represent 4.6 percent of the U.S. population, they represent 21.3 percent of the non-international members of the current freshman class. The Mid Atlantic region, covering the six states and Washington, D.C., that stretch from New York to Maryland, represent 15.9 percent of the U.S. population and 27.2 percent of non-international students in the Class of 2018.

According to the Admissions Office’s data, students who attended boarding school in Massachusetts are counted as coming from their home states, rather than their boarding schools’. Therefore, regional imbalances are likely even steeper than the data suggests.

As co-master of Cabot House, Dean of the College Rakesh Khurana embraces the important role that geographic diversity plays in House life and the individual student experience. “As a House master, I think that geographical diversity, like many other diversities of our experiences and lived experiences, enriches the Harvard College experience,” Khurana says.

In an attempt to create a geographically diverse incoming class, the Admissions Office has employed a myriad of programs, including direct email, letters, a new digital initiative called the Harvard College Connection, and exhaustive joint travel trips with colleges like Princeton, the University of Virginia, and Yale. In 2012, representatives from the Admissions

Office made visits to all 50 states, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Mexico. By their estimates, they saw almost 50,000 students and 3,000 high school guidance counselors.

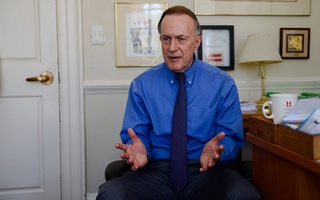

“Wherever you are, whatever kind of background [you come from]...we’re going to be at you with a variety of outreach efforts,” says William R. Fitzsimmons ’67, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid, with a distinct Boston accent, reflective of his childhood in Weymouth, Mass.

Despite an abundance of outreach efforts, Harvard saw only modest gains this year in the number of applicants from underrepresented areas.

“In every one of these geographic areas, they’re almost identical to last year,” Fitzsimmons, referencing the Class of 2019 applicant pool, said in an interview in February. “I could try to puff it up and say there’s a 16.1 percent [increase this year] versus an 8.1 percent change in Mountain states [last year], but that’s from 1,277 to 1,483 applicants. It’s not a big jump.”

Fitzsimmons and the Admissions Office are upfront and realistic about the challenges they face in terms of evening out these disparities in regional representation. According to Fitzsimmons, “80 percent of students will go to college within 200 miles of their homes, and 90 percent will go to college within 500 miles of their homes.” Fitzsimmons says this has been the case for decades and is a problem of which he and his office are aware during their outreach efforts.

Currently, the cornerstone of the College’s outreach stems from PSAT scores and contact information provided to Harvard by the College Board. From PSAT scores and other self-reported information, the Admissions Office sends mailings, both physical and digital, to students encouraging them to consider Harvard. According to Fitzsimmons, 63 percent of students in the freshman class, and 81 percent of minority students, were originally on the search list. “It’s a pretty good list, actually,” he says.

Despite their utility, Lucerito L. Ortiz ’10, an admissions officer who recruits and reads applications for Los Angeles, Southern Texas, and Latin America, says PSAT scores are an imperfect way to recruit students.

“The information that we have on students is very limited, because all we can go on really are PSAT scores,” Ortiz says. “It’s hard to find additional data on students.”

One aspect of Harvard’s outreach efforts that, according to students and admissions officers alike, draws a high number of applicants from underrepresented regions is its generous—and effectively marketed—financial aid program. Minnesota native Luke R. Heine ’17 credits the Harvard Financial Aid Initiative with prompting him to consider applying. Students from Heine’s hometown of Duluth do not regularly apply to Ivy League schools, as a perception of these colleges as preppy “Abercrombie Fitches,” as Heine puts it, is deeply entrenched.

“For me, the only reason I applied to Harvard and these Ivy League schools was that, being a pragmatic Midwesterner, I saw that the financial aid was very good,” Heine says. “I think that’s the best way to get people to even consider applying to these schools.”

{shortcode-d5b206082310a60b30df2ee51fcd2edadd39656f}

Dean of Freshmen Thomas A. Dingman ’67, who worked as an admissions officer from 1969 to 1973 before eventually transferring to the Freshman Dean’s Office, says he remembers covering parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Connecticut, and New York. In some of these states, recruiting applicants proved challenging.

“You’re out in the Black Hills in South Dakota, and so you work really hard to draw interest, and you find that someone who you think is a good applicant, and then that person doesn’t make it in the competitive process. And [when] you’re out in the Black Hills the next year there isn’t a friendly reception at the high school,” Dingman recalls.

Despite the Admissions Office’s attempts to level out the regional imbalances present in the current undergraduate population, administrators are quick to state that there is no quota of any sort for any particular background.

“This kind of outreach is really about finding people of excellence wherever they might be. There’s no quota for states; there’s no quota for countries, for that matter,” Fitzsimmons says. “A person from Kazakhstan will be competing against the person from Fargo when it goes to full committee. When the committee is actually making its decision, it’s really all about the excellence and the diversity that the student can bring, broadly considered.”

Perceptions abound, however, that an applicant from an underrepresented region will have an advantage in the admissions process.

“People used to laugh that the way to get into Harvard was to move from Boston to Wyoming,” Dingman says.

For his part, Jordan T. Colman ’15-16 has little doubt that being one of the few applicants from Wyoming was helpful.

“There’s this rhetoric that everybody has something that puts them over the top, right? And so, in some sense, I do feel like being from Wyoming is one of the things,” Colman says.

Eva A. Guidarini ’15, the former student president of the Institute of Politics, agrees. Despite moving cities frequently as a child, Guidarini attended George Washington High School in Charleston, W. Va., a place that she now calls home, both in her mind and on paper.

“It’s easier to stand out as an academic student in West Virginia than it is in Michigan, or in California, or any of the other places that I had lived [before moving to West Virginia],” says Guidarini. “I definitely am here because of West Virginia.”

Still, despite perceptions that coming from an underrepresented area can present an edge in the admissions process, there are other obstacles that these students face before they even fill out the Common Application.

Colman, a graduate of Natrona County High School in Casper, Wyo., was one of these coveted applicants from an underrepresented region. Colman estimates that only roughly 330 of the students in his class of 450 graduated. His road to Harvard reflects the challenges that Harvard currently faces when trying to recruit students from underrepresented regions.

“There was hardly an Ivy League culture at all,” Colman remembers.

Colman says Natrona County’s academic counselors heavily encouraged him to apply for the Hathaway Scholarship, which provides funding for students to pursue post-secondary education within Wyoming.

“It was preached and put on a pedestal, like the ultimate opportunity in higher education, and when I first talked to my counselor about wanting to apply to Harvard in particular, he wasn’t super into the idea,” Colman says.

The contrast between college counseling at a traditional New England feeder school like Groton, for instance, and Natrona County High School is quite stark. According to Colman, only one member of the team of counselors at his high school focused on college admissions and split his time between two schools. While Colman’s lone college counselor had over 3,000 students to advise, Groton has a team of three devoted to fewer than 400 students spanning grades 8 through 12. Of these three counselors, one serves on the board of the ACT, and another spent five years as an admissions officer at Georgetown.

According to Megan K. Harlan, Groton’s head of college counseling, every year four or five Harvard alumni make the trek out to Groton to interview applicants from Groton and surrounding schools. While Natrona County High School and Groton represent two ends of the spectrum, students like Colman say schools from underrepresented regions are less equipped to prepare students to apply to Harvard through its early action program. Last year, 992 of the 2,023 eventual admissions offers were extended to those students who had applied early.

Because Colman, like the majority of his high school classmates, didn’t start considering college applications until the fall of his senior year in high school, he says the early action program’s reinstatement for the Class of 2016 has put students from backgrounds like his at a disadvantage. (Colman entered the College with the Class of 2015.)

“Early action really favors kids who have a college counselor working with them one-on-one...and in my opinion, disadvantages kids like me from a state where you only go to public high school, where your college counselor is serving 3,300 students, where the scholarships in state are really, really good,” Colman says.

In an interview in October 2013, Fitzsimmons acknowledged the disparity in early admissions and said it would likely “continue to be the case for the foreseeable future.”

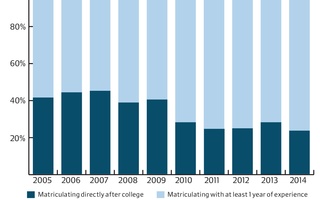

But in an interview for this article, Fitzsimmons strikes a brighter tone regarding the diversity of recent early action applicant pools.

“I think we’re winning the battle because you can see that early [action] now is much more diverse economically and ethnically than it was [in previous years],” Fitzsimmons says. “But it still isn’t reflective of what regular action is like.”

When Morris arrived on campus for his freshman year, he remembers only vaguely knowing two students on the entire campus, who were friends of friends. He says he remembers seeing students who seemed to already be a part of pre-set social groups. His first semester of freshman year was lonely and, at times, he felt overwhelmingly isolated.

“It’s very hard at the beginning [to make a friend group] and sometimes that can really set you out for a bad trajectory,” Morris says.

Today, midway through his sophomore spring, Morris says he has adjusted to social life at Harvard. Still, he remembers the difficulty in forming an entirely new friend group out of nowhere during the opening weeks of freshman year after moving from an area where he attended the same school and knew the same people since kindergarten.

Morris’s early experience on campus stands in contrast to peers from more heavily represented parts of the country like New York or Boston.

Nicholas P. Heath ’18, for example, estimates that he knew between 10 and 20 classmates from New York before coming to Cambridge and recalls spending significant time with these acquaintances during Opening Days.

“That was the easier thing to do,” says Heath, a graduate of the Collegiate School in New York City. “Why not hang out with people you already know?”

{shortcode-acb6239dad87d688bc920c6173def0cb5e5df802}

Mark S. Staples ’17 from Fargo, N.D., remembers viewing students like Heath from the outside. Staples is only aware of one other student from Fargo in his class, and they did not meet until they reached Cambridge. Staples remembers feeling surprised to find that some students already knew each other. “That was...a strange thought to me,” Staples says.

{shortcode-7def931fc37f18cbe8d5503d3428abce833aaf88}

Administrators, for their part, try to mitigate social inequities through rooming assignments. Dingman and his staff at the FDO view the task of finding lodging for students from numerous countries and all 50 states as an opportunity to create diverse rooming assignments. Through a five-week process, Dingman’s office takes geographic origin, amongst other factors, into account while formulating rooms and entryways by hand.

According to Dingman, some students request roommates from similar geographic origins—a Southerner may asked to be paired with another Southerner. While they try to form rooms that are geographically diverse, they sometimes try to fulfill students’ requests through special arrangements, like placing a student from a rural area in an entryway with a proctor or Peer Advising Fellow from the same region.

Despite the FDO’s efforts to create geographic diversity in order to enrich the rooming culture of freshman year, disparities in experiences still play out in student life once a new class has moved into the Yard. For students coming from rural areas, the adjustment to life in Cambridge is often described as a disorienting.

Luke J.M. Murnane ’18 is probably the closest thing Harvard has to a real-life cowboy. Sporting a cowboy hat and a massive belt-buckle, Murnane, who grew up on a ranch in Montana, describes the transition from rural Montana to urban Cambridge succinctly.

{shortcode-7e68cf27909154cae2e315d6413fb4d488beb511}

“It’s terrible,” he says with a chuckle.

Although Murnane says he is satisfied with the fast friends he made through the First-Year Outdoor Program and his entryway in Apley Court, he continues to criticize city life. In an effort to simultaneously escape the bustle of Cambridge and stay in touch with his equestrian roots, Murnane joined the Harvard Polo Club, which practices an hour away in Hamilton, Mass.

Both Staples and Heath say that as their freshman years progressed, social life became less tied to geographic areas of origin. Although Heath says he has noticed that a lot of blocking groups are “New York heavy,” most of them have at least a few students from other places.

According to Dingman, many blocking groups form from individual entryways, which inherently include much of the geographic diversity originally drawn into the rooming assignments.

But the transition to Harvard from an underrepresented part of the country is challenging during more than just the first few weeks of freshman year. Just as Staples’s transition from rural Fargo to urban Cambridge was difficult, Morris’s adjustment from high school to college academics was similarly challenging. According to Morris, his alma mater was more “focused…on athletics” than academics. His high school and middle school often weren’t able to afford new textbooks, leaving the students to make do with insufficient, outdated resources.

Tessa A.C. Wiegand ’15, a former columnist for The Crimson, hails from Morgantown, W. Va. While Wiegand took the maximum number of Advanced Placement classes her high school offered, she was surprised by the access that her Harvard peers had had to college level classes such as multivariable calculus. Though Wiegand finds that Harvard does a good job of providing a wide range of course levels, administrators are considering adding more programming to support students who had fewer academic opportunities in high school.

Wiegand, who is now an applied mathematics concentrator, overcame her personal academic setbacks, but says that much of her experience as a West Virginia native at Harvard was defined by social stereotyping. Wiegand often finds that negative assumptions about West Virginia affect her introductions to new classmates.

“I mentioned in the article that somebody apologized for me being from West Virginia,” says Wiegand, recalling an experience she discussed in an op-ed she wrote for The Crimson in 2013. “That was in an introductory conversation, like, ‘Hi, I’m Tess, I’m from West Virginia.’ And the response was, ‘Oh, I’m sorry.’”

Guidarini, who also calls West Virginia home, adds that professors have made comments about the state in class that she has found offensive.

“Friends tease everyone about everything, so a close friend teasing me about West Virginia bothers me zero,” she says.“I think it’s the professorial reactions that bother me the most.”

On one instance, Guidarini says, she remembers a professor asking how much money her “poor coal mining friends make.”

Preconceptions cut both ways. Some students from more established feeder communities and high schools say they also face being stereotyped as privileged or elitist because of their high school backgrounds.

“When you tell people you’re from New York, they immediately develop a certain sort of perception of who you are, your background and privilege, that sort of stuff,” Heath says. “There does exist a New York stereotype, and when you tell people you’re from New York, you do run the risk of them instantly assuming that that stereotype applies to you.”

“I’ve worked at Andover, St. Paul’s, and Groton, and so I think that’s something that the school has to combat,” Harlan says. “That’s something that the students that graduate have to combat.”

Even after the initial college transition, there are disparities between the experiences of students who hail from different parts of the country. When students look to join one of the College’s hundreds of student organizations, they make the friends that will come to define their time at the College. Some groups cater disproportionately to groups of students from highly represented regions like the Northeast or New York, though, and some students from other areas are looking to create their own to combat that influence.

The Hasty Pudding Club, a co-ed social club that begins to recruit students their freshman fall, has drawn criticism for a membership that favors students from certain geographic areas.

In the Hasty Pudding Institute of 1770’s 2014 annual report, undergraduate Hasty Pudding Club President Matt G. Wardrop ’15 addressed the organization’s strides in reaching a diverse range of students in their annual fall punch. “Much like Harvard College, we view diversity as being at the very core of the Pudding experience,” Wardrop wrote, citing a membership base ranging from Cambridge to “as far as Australia’s Gold Coast.”

The numbers tell a different story. Data from the HPC’s fall 2013 punch class, detailed in a critical Crimson op-ed last fall and crossreferenced with data from The Crimson’s Class of 2017 freshman survey, show that 77 percent of HPC punches hail from the Northeast region, compared to 41 percent of students who identified as such in the entire class. Furthermore, 85 percent of HPC punches attended private school, according to the data, compared with 39 percent of the Class of 2017 as a whole.

Wardrop did not respond to requests for comment.

Though the Hasty Pudding Club nears its 250th birthday, its membership does not reflect the same trends in diversity as does the larger student body at Harvard. Outside of the club’s walls, undergraduates have found alternative ways for underrepresented students to socialize.

{shortcode-ebaa06020e228f482acd30ca9a326c196415f652}

Ashford L. King ’15 of Versailles, Ky., is only two months from graduating from Harvard, but his tenure as an undergraduate has been marked by a consistent trend that he plans to address before leaving. King says he has been meeting peers from Appalachia since freshman year, but has had no real way of getting together and forming a community on campus. He’s currently forming a club for students from Appalachia.

King says the formation of the club is the optimal approach to combatting the geographic stereotyping he has encountered throughout college.

“I figured, why not start an organization that on one level serves a social purpose and just provides a forum for us to get together and talk about what it’s like to be Appalachian at Harvard,” King says.

While King waited until his senior year to get the Appalachian Club started, Heine first had the idea of starting a Midwest Club during his freshman year.

By last fall, the club was in full swing, and it’s already popular; more than 200 students have signed up for the email list. “Because so few Midwesterners come to Harvard...there’s a real camaraderie in these communities,” Heine says. Heine acknowledges, however, that despite the Midwest Club’s success, it suffers from a lack of resources. Unlike some other undergraduate clubs at Harvard, the Midwest Club does not own real estate or have consistent access to a meeting space. Large parties have been out of the question so far, and the club’s dinners in the Leverett House’s small dining room must be lotteried due to space constraints.

{shortcode-0ff89cfade459269341f6e11cd46dd87941483df}

“It’s antithetical in some regards to the Midwest Club because the Midwest is an inclusive space, and it really sucks to have to lottery that and make it seem exclusive,” Heine says.

When Guidarini graduates from Harvard in May, she will not be returning to her beloved hometown of Charleston, W.Va. She loved living in West Virginia, she says, but she can’t see herself moving back there for now. “There just aren’t the opportunities that I want there,” she says.

Guidarini is not atypical. While slightly more than 40 percent of members of the classes of 2017 and 2018 who participated in The Crimson’s annual freshman surveys reported that they are native to the Northeast, more than 70 percent said they want to live there after graduation. And while 11 percent of Class of 2018 respondents identified as coming from the Midwest, only 2.3 percent envision themselves living there after

For some undergraduates who hail from outside the highly represented Northeast, returning home is inevitable—“The second I graduate, I’m going back out West,” Murnane says—but others realize after struggling to adjust to life at Harvard that their hometowns may not offer the same opportunities, in the workforce or otherwise, that Harvard graduates come to expect in New York or Boston.

Harvard’s incoming classes represent a skewed map, and that trend does not stop after graduation. Sixty-four percent of graduating seniors who responded to The Crimson’s survey of the Class of 2014 last year reported plans to live in New York, Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., or California after graduation. Just 39 percent of respondents, however, came to Harvard from those places.

Colman describes his desire to return home to Wyoming after Harvard as an obligation to contribute “some social good” to his home state. Still, he recognizes the issues inherent in moving back to an area that may not offer all the professional opportunities a more urban environment affords.

“I don’t know that Wyoming has everything I would want,” Colman says. “I imagine the way that I’ll compromise between my obligations and my hope for more opportunities is that I go back West...but it may be in a city out West—in Denver or Salt Lake.”

—Staff writer C. Ramsey Fahs can be reached at cfahs@college.harvard.edu. Follow him on Twitter @RamseyFahs.

—Staff writer Forrest K. Lewis can be reached at forrest.lewis@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @ForrestKLewis.