People call Michael Cuesta’s film “Kill the Messenger” a political thriller, with some justification. It has its fair share of brassy thriller-type scenes: arrests, intrigue, threats, chases, and untimely revelations. In its truer moments, though, it’s a work about slowing down. The movie tells the true story of how American journalist Gary Webb (Jeremy Renner) wrote an article in the 1990s exposing corruption in the US government, tasted fame, then paid for it. In ancient times, messengers bearing bad news could be slain on the spot, but Cuesta’s film reminds us that we are in the modern age. Webb slowly died a living death. It appears that the movie’s real ambition is to show the pain of this human erosion—and it might have succeeded in this goal had the focus remained on this one worthy approach. But the film, like its protagonist, ventures too far out.

{shortcode-d9c906e12f68c0d6685831f4986d87c42442be68}

There is no doubt that this work tries to say a lot. The beginning shots rapidly alternate between news headlines, documentary footage from speeches by ’80s presidents on the drug wars, and footage of the Nicaragua Contra fighters on the ground; meanwhile, suspenseful music pounds, and headings are, fittingly, “typed” out on the screen. Look at me, these boisterous images seem to holler: I am going to tell you all these very important and scary things! About American history! About journalism! About the CIA! Part of the movie is an exposé of the US government and its collusion, via the CIA in the Reagan years, with drug dealers and the human-rights-violating Contra fighters. These details were adapted from the book] “Dark Alliance,” which Webb eventually wrote to defend his article after it came under attack.

These supposedly more thrilling aspects of the story in fact do not command one’s attention very well. The film certainly isn’t great as a thriller, and that’s partly because the structure sprawls. Its documentary-history-type threads are more disorienting than helpful. Their new developments flash into the movie so fast that it is hard to keep up, and they make it more difficult to take in the other, very differently toned biopic side of the movie.

At the intersection of those tangled strings lies more interesting matter: Webb’s declining life, brilliantly acted out by Renner. The film shows how Webb roasted as a lamb on the altar of the media and CIA, the victim of smear campaigns to discredit his work and his person; he lost his family, job, and mental health. To that end, Renner’s Webb sports a pair of aviator sunglasses at the start of the film but wears them less and less as time passes. At some point he cannot protect himself from scrutiny anymore. His exposed eyes, like himself no longer hiding behind the screen of small newspaper journalism, grow haggard as he takes his invisible beating. But they seem to gather strength too. It becomes less easy to avoid their stare and its quiet accusation.

Renner, whose eyes are passionate but almost boyish, is visibly not the person of the real Gary Webb—as an actor he is more likeable, more the energetic modern type. His version of Webb’s against-the-establishment affect therefore feels a touch exaggerated. On the other hand, it works well with the idea of the movie, which is, basically, to convey a sense of Webb’s increasing agitation and desire to thrash around even while he is increasingly paralyzed. Notes after the movie’s end state that Gary Webb died in 2004, apparently from suicide.

The film’s central image anticipates its tragedy: at a holiday dinner in Webb’s home, the camera pans up the long meal table towards its head. Its speed is ominously slow. Webb’s family looks arranged like that happy domestic tableau in Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom from Want,” but in dark lighting. Precisely the lagging quality of this moment is what makes the viewer shudder, bracing for the inevitable bursting open of this heavy cloud.

The movie feels incomplete at the end. Renner’s figure of Webb walks away from his family up a slowly ascending escalator, a vision in a hazy cloud of romance and tragedy, suggesting Christian imagery of the resurrection. Alongside its namesake book by Nick Schou, this film is in a way Webb’s resurrection. The doomed messenger of ages past, a generic figure caught in the political machine, becomes Cuesta and Renner’s glorious Gary Webb: individual, great man, a sort of American Prometheus posthumously unbound. The question is whether to approve of Cuesta’s hagiographic treatment. Probably not in this secular age.

Still, the film’s brave passion is admirable, as is its intent—if it isn’t formally as unassailable as it could have been. It does seem to stare its own viewers in the eye, though, and boldly dare us to not dismiss it so easily. Like the real Webb himself, who shows up in a haunting image playing with his three kids at the end and whose presence seems unspokenly to inhabit the film everywhere with Renner’s Webb. We must not kill the messenger, after all. Nor the medium.

—Crimson staff writer Victoria Zhuang can be reached at victoria.zhuang@thecrimson.com.

Read more in Arts

'The Best of Me' Lacks SubstanceRecommended Articles

-

Need to Focus? Try These Tools

Need to Focus? Try These Tools -

Faber's Most Recent 'Strange,' 'New,' and Underdeveloped“The Book of Strange New Things” raises fascinating and worthwhile questions, though its answers remain inconclusive or noncommittal.

-

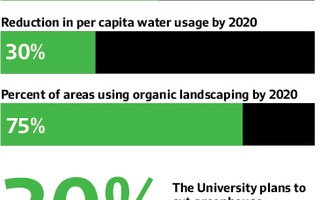

University Sets New Goals for Curbing Consumption, Waste

University Sets New Goals for Curbing Consumption, Waste -

Service Should Not Be RequiredRequiring such activities is not the best way to foster in students a love and appreciation for service to their community.

-

What Title IX DoesWe write as alumnae who have witnessed the law school’s failure to serve survivors, and who believe that our professors’ willingness to outrightly reject an improved-but-imperfect policy perpetuates that unacceptable legacy.

-

A World Exists Beyond Harvard and Here's What's Going on in It

A World Exists Beyond Harvard and Here's What's Going on in It