Michel Faber’s novels take place in vastly different settings, all of them peopled by a unique cast of characters. Yet his stories share a common interest in unraveling the mysteries of human nature, and “The Book of Strange New Things” is no exception. The novel broaches the topic of religious faith in a way unusual in fiction: with an appreciation for its inextricable link to the other myriad complexities of humanity. But this endeavor to examine the nature of faith falls a little flat when outside circumstances, rather than a character’s volition, begin to resolve some of the book’s toughest decisions. “The Book of Strange New Things” raises fascinating and worthwhile questions, though its answers remain inconclusive or noncommittal.

Like Faber’s other books (“The Fire Gospel,” “The Crimson Petal and the White,” “Under the Skin”), “The Book of Strange New Things” has a compelling premise. It imagines a near future in which intergalactic travel is possible and the made-up corporation USIC has set up a colony on a planet called Oasis. The narration follows a pastor named Peter to this new world where he has been hired to minister to the mysterious natives, putting many lonely light years between him and his beloved wife, Beatrice, back on Earth. Faber depicts this possible near future with confidence: he doesn’t shy away from scientific questions and allows Peter to ponder some of the problems that may occur to the reader (outer-space travel and the evolution of alien species, for instance). He renders the environment of this far-away planet and its inhabitants so realistically that one can hardly believe they don’t in fact exist somewhere. Spiraling rain currents and faces resembling walnut kernels clearly don’t follow the laws of this world, yet they are described consistently enough and with just the right amount of natural variation to convince readers that these phenomena must follow some set of rules.

Faber excels at creating meticulous, believable environments. However, the science fiction premise of “The Book of Strange New Things” is perhaps first and foremost the setup for an exploration into the psyches of its characters. Central to this exploration is the riddle of religious faith. Faith is hardly an untouched issue, but it’s sometimes avoided in fiction that doesn’t have a specifically religious message. A fictional character labeled as religious may threaten to alienate nonreligious readers. However, Faber provokes his readers to reconsider religion and religious faith, which he very quickly establishes as fundamentally linked to universally relatable fears, desires, and emotions. Then he probes the nature of faith, along with its intersections with love and friendship, under strange and varied conditions.

Unfortunately, given that the novel makes human nature its focus, some of the insights it provides are disappointingly rudimentary. This is in part due to the narrative’s hypothetical scenarios that are at times so extreme that it seems Faber’s characters are simply riding the roller coaster of the plot. Characters remain enmeshed in the same angst until external factors drive their hands and force them to make one decision or another, so that the reader never sees them go organically from a simmer to a boil. And it’s hard to imagine that, allowed to simmer, Peter wouldn’t come to a natural boil; his personality is impressively well developed. In fact, Faber gives practically every minor and major character a past that motivates them and a balance of positive and negative traits. Nonetheless, the book can feel claustrophobic. The men, women, and natives of Oasis, despite being three-dimensional, are often more like saplings in winter than full-foliaged trees and are blatantly pigeonholed by their races. One could argue this is a point in the book’s favor, as it forces the reader to experience more thoroughly the isolation of a faraway planet. But even Peter, the book’s protagonist, is rather tiresome to spend so much time with.

“The Book of Strange New Things” has many successes. It excitingly opens up the topic of religion, so often glossed over, and unites faith with the rest of the human psyche. The reader is privy to the interactions of faith with love, faith with anger, faith with loneliness. Even the discomfort some people have with religion is tackled straightforwardly, enacted through Peter’s nonreligious coworkers. Still, with all these achievements, some readers may find themselves a little disappointed at the end of Faber’s newest work. The plot appears elegantly set up to examine human nature, but when this examination seems to be going in circles, the book begins to lean too heavily on the events of its narrative, which aren’t quite strong enough to support the weight on their own.

Read more in Arts

What's the StoryRecommended Articles

-

In Search of Lost Time

In Search of Lost Time -

New Concentration Was Years in the Making

New Concentration Was Years in the Making -

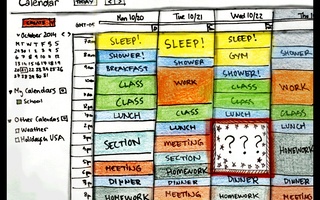

Harvard Today: October 23, 2014

Harvard Today: October 23, 2014 -

What Title IX DoesWe write as alumnae who have witnessed the law school’s failure to serve survivors, and who believe that our professors’ willingness to outrightly reject an improved-but-imperfect policy perpetuates that unacceptable legacy.

-

'Some Luck' Gets Something RightReading Jane Smiley’s new novel, “Some Luck,” one becomes increasingly aware of a simple truth about time: all of history was once the present, and the present will one day be history. Of course, this is a fact one knows in theory, but to make someone truly grasp the concept and its implications is not a trivial undertaking.

-

Women's Volleyball Downs Dartmouth in Straight Sets

Women's Volleyball Downs Dartmouth in Straight Sets