In the seventeenth century, Harvard students were required to take three years each of Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, and Syriac as well as demonstrate fluency in Latin as part of their graduation requirements, according to The Crimson.

In 1968, the Harvard faculty voted to introduce the one-year language requirement that College students know today. Students can demonstrate their competency at a foreign language through SAT or Advanced Placement scores, or by achieving an adequate result on Harvard’s language placement exams.

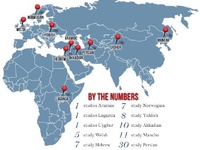

But for those who still need to fulfill their language requirement, or wish to expand their language capabilities, Harvard consistently offers more than 80 languages each semester. While widely-spoken tongues like Spanish and French attract the most people, students enrolled in obscure language classes say that although those programs may have a smaller presence on campus, Harvard is willing to accommodate their language needs.

A NATIONAL LANGUAGE RESOURCE CENTER

As of press time, seventy-seven College students are enrolled in the beginning level French Ab course this semester. One-hundred-and-fifty-three take Spanish Ab. Intermediate Welsh has one student.

Catherine McKenna, chair of the Celtic languages and literatures department and a professor of Welsh, says she thinks students may not immediately be attracted to her class because unlike the highly-enrolled romance languages, it is not “in an English speaker’s comfort zone.”

Daniel R. Rafinejad, a language preceptor who teaches beginning Persian, says students may not want to study the language because they have limited access to countries like Afghanistan, Iran, and Tajikistan, where the language is spoken. The elementary Persian class taught by Rafinejad enrolls seven undergraduates.

Welsh and Persian are not the only languages to which Harvard devotes resources despite small enrollment numbers. This semester there is one undergraduate each studying Luganda, Uyghur, and Akkadian.

While interest may be small, Harvard does what it can to accommodate those who wish to take uncommon languages.

According to professors and students, Harvard will occasionally offer additional language courses if a student demonstrates a curricular or academic need for taking the class.

Michael T. Feehly ’14, a history concentrator with an interest in Scandinavian studies, found himself unable to study the Norwegian language because Harvard did not offer classes past the introductory level. Feehly petitioned the Administrative Board to increase Norwegian language offerings, arguing that he needed them to continue his thesis work. Last semester he was the only student enrolled in Norwegian Ba.

“It’s literally me and the [teaching fellow] in a room for an hour,” Feehly said in December. “It’s kind of stressful because basically all of the attention is on me.”

Harvard’s dedication to supporting obscure language courses has garnered recognition from the federal government. The University has been designated a National Resource Center for Foreign Language, Area, and International Studies under the US Department of Education Title VI, and as a result received $1,184,483 in 2012 to fund languages labeled as “African,” “East Asian,” “Eurasian,” and Middle Eastern.” It will receive the same amount of money for those languages in 2013.

“If you can’t study it at a place like Harvard—if you can’t pursue ancient languages, obscure languages like Akkadian..., languages that don’t exist anymore—if Harvard doesn’t teach them, where will they be taught?” says professor Mark C. Elliott, who teaches Manchu.

A WORTHWHILE PURSUIT

Obscure languages offered at Harvard face challenges when trying to attract students. Those languages like Spanish and Chinese that garner the largest enrollments are spoken around the world and can add critical skills to a resume.

Even so, those involved in Harvard’s uncommon language programs maintain that the courses are worth preserving.

“The number of speakers of a language does not determine how important a language is,” says Feehly.

Students and professors say they often face questions about why they devote time to learning something many may consider impractical.

Elliott says the language he teaches derives its academic value from its historical applications.

One out of every five documents from the Qing Dynasty, of which Manchu is an endangered primary language, is written in the language, according to Elliott. Because of his knowledge of Manchu, a language known by very few people, Elliott was able to investigate documents that had never been read before.

Students choose to take uncommon languages for a variety of reasons. Elena F. Hoffenberg ’16 says she was drawn to the study of Yiddish for personal reasons. “On a very personal level it’s a way for me to connect with my predecessors,” she says. The five students enrolled in McKenna’s Welsh class chose the language in order to pursue everything from thesis work to “ something interesting and off-beat,” says McKenna.

For Elliott, the University is a prime location for exploring obscure languages.

“Harvard is the kind of place where people need to be able to pursue esoteric subjects,” he says. “The world looks to Harvard to provide instruction in exactly those kinds of areas—that is one of the beautiful things about Harvard.”

—Staff writer Neha Dalal can be reached at nehadalal@college.harvard.edu, Follow her on Twitter at @theneha.

—Staff writer Indrani G. Das can be reached at idas@college.harvard.edu, Follow her on Twitter at @IndraniGDas.

Read more in College News

OCS Discusses Workplace Discrimination and DiversityRecommended Articles

-

Racquetwomen Lose Twice; Men Squeak By YaleThe men's squash team narrowly squeezed by Yale, 5-4, and finished off its 1978 regular season with a contest that

-

Desaulniers Roars But Racquetmen Eaten Alive, 8-1Describing the men's squash match with Princeton on Saturday afternoon as anything but anticlimactic would be like saying Mike Desaulniers

-

Cambridge City Council Candidate: Larry WardLarry Ward would like to involve the Harvard community in many of the ideas he hopes implement should he return to the Cambridge City Council after the November election.

-

Harvard Introduces First Gen Ed Curriculum, Travels to Nixon's Kitchen Debate, and Hosts Olympic Soccer

Harvard Introduces First Gen Ed Curriculum, Travels to Nixon's Kitchen Debate, and Hosts Olympic Soccer -

Harvard Law Grad Suspected of $100 Million SchemeJohn D. Cody, a Harvard Law School graduate, was arrested last Monday on charges of fraud up to $100 million over an eight-year period. He used a fake charity to collect donations from 41 states, under the pretense of helping Navy veterans, according to the Huffington Post.

-

For the Record: "XO"Arts writer Se-Ho B. Kim revisits Elliot Smith's emotionally resonant album, "XO." "Although “XO” is an album that taught me the art of breaking up, it ultimately helped me put myself back together. At the very least, it helped me come to terms with the part of me that wanted things to fall apart and for me to forget."