Simply put, according to Stout, “The park really wasn’t ready.”

***

On the mound for the Crimson was junior Sam Felton, class of 1913. The stocky son of a railroad magnate shed the heavy, full-length fur coat he was known to wear and toed the rubber. Better known as Harvard’s star kicker on the gridiron, Felton would be facing a Red Sox lineup that included most of its regulars, including the famed “Golden Outfield” of Duffy Lewis and future Hall of Famers Harry Hooper and Tris Speaker.

Though Felton would later be offered—and decline—a $15,000 contract by the Philadelphia Athletics, the hurler did not have his best stuff amidst the snow and struggled to find the plate.

“They were playing on a field that really, with the exception of the infield grass, was probably mostly mud, and was very slick,” Stout says. “It was a game that was pretty rough around the edges.”

Multimedia

Felton hung in against the major leaguers, getting Hooper to fly out to deep left to begin the home first. After Steve Yerkes singled to right for Fenway’s first hit, Felton got out of a bases-loaded jam to keep the game scoreless after one.

But after the Crimson again went down in order in the top of the second, the Red Sox broke through as Felton struggled with his control. Following walks to Marty Krug and Pinch Thomas—who advanced to second and third on an errant pickoff attempt in which, according to The Crimson, “No member of the University team [was] on hand to take the throw”—Hageman helped himself with a single to right, knocking in Krug for the park’s first run.

Felton got out of the inning with no further damage after Hooper flew out, Yerkes struck out, and Speaker was forced out at second following a walk.

***

With the poor ticket sales and even worse weather, the few seats in the stadium were sufficient for the 3000-person crowd, which consisted of many folks dressed in wool coats fit for the mid-30s temperatures.

“They had hoped to make a killing that day, and I think they probably hoped they’d get 10 or 12 thousand people,” Stout says. “But the weather was really poor, and that just didn’t happen.”

Indeed, there was not much about the afternoon that made it fit for baseball, and that limited the Red Sox’s interest in playing at all. The team had arrived in Back Bay Station the previous day after spending all night traveling by train from Cincinnati. Upon returning, many had stayed at Put’s on Huntington Avenue, despite the fact that the hotel was much closer to their old stadium—the Huntington Avenue Grounds—than their new one. Others had secured accommodations at the Copley Square Hotel, about twenty minutes by foot from Fenway.

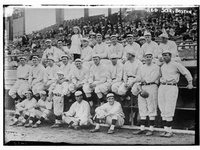

The following afternoon, the squad headed to Park Riding School on Ipswich Street to pick up their uniforms, as the Fenway clubhouses were still unfinished. The players were dressed in their home whites, with the words “Red Sox” emblazoned across their chests in red, and they wore white woolen caps and white socks with a wide red stripe that surrounded their calves and gave them their nickname. From the school, they walked to the park in uniform, though they were in no rush to get to the stadium and so remained in their makeshift clubhouse playing cards and stuffing tobacco until the last possible moment.

The Crimson players, likewise, were in no hurry to head over from campus, where they had dressed. Though Harvard was excited to play on a big league field, the occasion marked the first time all year that the team would even have the chance to play on a real field at all. Most of the Crimson’s practices to that point had taken place indoors, and the team had yet to play a game outside.

“Previous to this,” The Crimson reported on April 6, “the battery men had been working in the cage since the mid-year period; fielding candidates except ‘H’ men since the first of March, and the ‘H’ men since March 18.”

Read more in Sports

Pair of Victories Highlight Weekend for Track and Field