Indeed, the emotion most encompassing the sophomore from Winchester, Mass. was likely that of intimidation. Four years earlier, Hageman, the 25-year-old right-hander he was now facing, had thrown a pitch that had drilled Charlie “Cupid” Pinkey of the Dayton Veterans behind the left ear and subsequently killed him.

The hurler had been so mortified that he had taken the following season off, and after two years in the minor leagues in Denver, he was fighting to make the Red Sox squad.

“The papers said he was the $5,000 prospect,” says Red Sox Vice President Emeritus and Team Historian Dick Bresciani, referring to the seemingly extravagant price Boston had paid to purchase Hageman from the minors.

The Harvard roster was still wide-open as well; as The Crimson reported that day, “The make-up of the team is still unsettled, and in all probability nearly everyone will be given a try-out this afternoon.”

Though Wingate was a good bet to make the team, the third baseman was nonetheless overmatched by Hageman, who threw a first pitch ball before striking Wingate out on a series of fastballs.

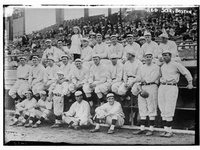

Multimedia

Hageman then retired Crimson shortstop Dowd Desha and left fielder Richard Babson with ease to finish off a 1-2-3 opening inning.

***

Even though it was the park’s first game and the Red Sox had touted the appearance of “Old Timers”—a collection of Boston ballplayers from the 1860s onward—the public had shown very little interest in the contest.

“It’s important for anyone looking at [the opening of] Fenway 100 years ago to realize it was nowhere near as big a deal as it would be today,” Stout says. “Any anticipation was probably tempered somewhat by the fact that everybody was just trying to stay warm.”

Yet had anything close to a capacity crowd turned out, thousands of fans would have had nowhere to sit.

Indeed, the park was still very much a work in progress, with the construction shacks having only been removed a few weeks before. Much of the outfield was covered in footprints from the men who had worked tirelessly over the previous week to finish the bleachers and erect a fence to enclose the park.

As the game began, crews of workers continued bolting seats into the grandstand, working from the lowest rows up. Only a few thousand seats were then in place, while thousands of others were stacked beneath the stands, protected from the weather. They would not be installed for another few days.

In the concrete boxes down below, separated from each other by pipe railings, workers carried stacks of folding chairs up the ramps from below the stands and arranged them in neat rows. Fixed seats were never intended for the boxes.

Grass was sparse thanks to the weather, and outside the infield, bare ground dominated. In front of the fielders was an immense grandstand, 510 feet long from end to end. A mesh net that stretched from its roof was intended to protect fans from foul balls, but it did not yet cover the box seats.

On each side of the infield was a 40-foot-long concrete dugout, with the visiting Crimson along the third-base side. The dugouts contained a bench for the players to sit on, a set of concrete stairs leading to the field, and a pipe rail fence to prevent fielders from falling in while pursuing pop-ups. There was barely enough room for everyone to fit.

Read more in Sports

Pair of Victories Highlight Weekend for Track and Field