They say you always remember your first time.

For me, it was a clown handing out balloon animals at the public library. I was four years old. I was drawn toward the colorful creatures shaped out of a little bit of squeaky rubber—and it was love at first sight.

I took my balloon home, sat down on the kitchen floor, and painstakingly figured out how to take it apart. When I had finished, I pinched and squeezed, trying to put it together again.What else could I make out of it? How many times could I twist it before it—oh.

I’ve felt that sharp sting of latex snapping in my palms hundreds of times since then. And every single time, all I’ve wanted was the chance to get my hands on one more balloon.

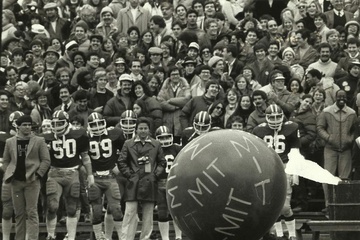

In the 17 years since that day at the library, I’ve sold balloons in three countries, turned in a 60-balloon dragon instead of a response paper on Beowulf, and been hired to clown at carnivals, birthdays, a bat mitzvah, and the Harvard-Yale tailgate.

I spent two summers working as a balloon artist at Friendly’s, an East Coast restaurant chain known for its ice cream and service so slow you need balloons to forget how long you’ve been waiting in your red vinyl booth. Those summers, I went through more than 3,000 balloons each year. I learned new animals—a chicken, a turtle—based on my customers’ requests. I became acquainted with the people of Friendly’s, too.

One man had come there for the $9.99 dinner-drink-and-sundae meal every single night since his wife died in a car accident; he was usually alone or occasionally with his utterly silent son. One waitress frequently cornered me near the kitchen to ask me for sexual balloons. A diner tried to convert me to Christianity, using the red cellophane decoder toy that came along with the children’s menus to represent the blood of Jesus.

One woman took in my situation—standing in a gaudy chain restaurant just off the expressway in an insignificant town in Pennsylvania, making balloon animals in a rainbow-striped shirt and a name tag that said “Zippy”—and asked me witheringly, “Can you do anything else?” Hyperactive Little League baseball teams asked for 19 balloon animals, and their coaches didn’t even tip me for all those snails. Children handed their erstwhile balloon dogs back to me to be twisted up again, shapes unrecognizable and surfaces sticky with ice cream and worse.

But at another table, a group of little girls made up a “Zippy the Clown” song. I held up a balloon bicycle above the tasteful glass barriers criss-crossing the restaurant one night and the entire clientele responded with applause.

And even when I had twisted a horse or a flower a thousand times, for some reason I never tired of my desire to play with malleable latex. When it’s your job to smile, at some point it stops being an act.

In high school, when anyone asked me where I was going to college, I told them I would be attending the Ohio College of Clowning Arts. After three months, I would run away and join the circus.

I guess my plans changed after that. A year later, after a freshman year that was magical in its own right but included no rabbits in hats on syllabi, the waitresses at Friendly’s were telling their customers, “You know the clown, Zippy? She goes to Harvard.”

A hilariously high number of people responded, “Harvard? Do they have a clown major there?”

Back then, I would always laugh it off. “No,” I said shamelessly. “I’m doing this to help make money for college, so I can do something else with my life!” That usually got a dollar or two out of them.

Yet despite what I told my Friendly’s customers, I’m not so sure I don’t want ballooning to be a major part of what I do with my life. I’ve looked into it. To be a Certified Balloon Artist, one must complete several written exams covering balloon décor, bouquets, and delivery, as well as a four-hour-long hands-on test. There are more than 2,500 CBAs working today. They meet biannually at the World Balloon Convention, where artists from around the world compete for prizes in balloon table arrangements, sculptures, hats, and fashion.

I’m not certified yet, but I’ve been making bigger and bigger balloon sculptures. I made a four-foot-tall Big Ben to celebrate the London Olympics over the summer, then spent hours designing and sculpting my huge red dragon in the fall. Come Halloween, I made an all-balloon witch costume—fully wearable dress, pointed hat, broom, poison apple.

But in between running Harvard’s charitable clown club and dropping balloons in front of the doors of students in my House on their birthdays, I’ve mostly spent my time at Harvard trying to become a journalist. Lately, I applied for a post-graduation internship at a newspaper I would truly love to work for. The application asked, “What careers besides newspaper journalism are you considering?” I debated putting down some field like publishing or social work or law.

But at this moment, all of those are pale second choices to journalism. The only occupation that would genuinely make me as happy as reporting, I know, is balloon twisting. Though I feared that the editors evaluating my internship application might think I was being flippant, I answered “balloon artist,” and I meant it.

At Friendly’s and anywhere else I clown, I’ve become accustomed to the people, usually men in their teens and twenties, who seem to find it amusing to try to stump the clown. “I want a T-rex,” they say. “I want a guitar.” Thanks to the movie “Wedding Crashers,” they demand, “Make me a bicycle, clown.”

“Sure. What color?” I ask evenly.

I revel in the chance to impress those guys who thought they were too old, to watch the carefully constructed bravado on their faces fade to childlike joy as I twist a whimsical creature—or a realistic bicycle from five balloons—out of the air in front of them.

That pursuit, the quest to see yet another person’s eyes light up when he first recognizes the shape his balloon is going to take—whether he’s three years old or he’s 103—is not all that different from my love of writing. When I write fiction, or when I report a news story, just like when I make a balloon, I am striving to craft a little something that seems original, that rings true to life, that is beautiful.

Like an excellent news article, an excellent balloon makes life look a little bit different. You didn’t know when you heard you were getting a penguin or a monkey in a tree what that might look like in balloons. All of a sudden, you can see it. And you didn’t know that a children’s toy could make you so happy, but as it materializes, without fail you’re grinning no matter how old you are.

By making a balloon or creating a story, an artist uses her hands and her spirit to surprise her audience, to shatter some of the cynicism and narrow-mindedness that cake our boring grown-up hearts.

Sometimes to burst illusions, you need something poppable.

—Julie M. Zauzmer ‘13, the Managing Editor of The Harvard Crimson, is an English concentrator in Pforzheimer House. You may know her as that girl in the pink wig and big shoes in your dining hall.