A Belmont Starbucks at 8 a.m. on a Wednesday morning is not a soulful place, but still it has its rhythm. Mothers on autopilot pick up their coffee, baristas correct orders of medium with murmurs of “Grande,” and high school girls anticipate the rest of their day and caffeinate. Michael Reavey has his rhythm, too. The trumpet player of local soul band The Chicken Slacks arrives a full 15 minutes earlier to our interview than musicians are supposed to (15 minutes late) and leaves on the hour to prepare for the work of the day; Reavey also teaches music lessons. For The Chicken Slacks, Wednesdays have meant the same thing for the past seven years: the day before the Thursday night gig at the Cantab Lounge.

At first glance, The Chicken Slacks may seem like any other wedding band—an assumption only encouraged by their appearance as a generic wedding band in the film “Bride Wars.” Yet this is not a group that only plays affirming, anesthetized soul music at the bar mitzahs and weddings of the nostalgic. Though playing at the same bar every week for seven years is not glamorous, that gig is what separates The Chicken Slacks from the average cover band. While their primary goal is to entertain, they are committed to the preservation of soul and its authentic presentation, and it is this mission that they carry out for three sweaty, alcoholic hours every Thursday into the wee small hours of the morning.

IT’S YOUR THING

In 2001, Justin Berthiaume, founder and former drummer of The Chicken Slacks, was a full-time musician in Boston. Contrary to popular belief, full time musicians are not either starving or Taylor Swift. More often, those doing music professionally make a living by giving music lessons or playing one-off gigs as a sub for local bands. Michael Duke, the guitarist in the Slacks, occasionally teaches at Berklee College of Music. Jeremy Valadez, the band’s saxophonist and musical director, is an expressive arts therapist in training. Back in 2001, Berthiaume was well-established in the blues rock scene, but even with a solid living he found something lacking.

“I was a drummer around town and I wanted to take it to the next level and be one of the best musicians in town if I could,” explains Berthiaume via Skype from San Francisco, where he now teaches environmental science at a public charter high school. “I started getting into the blues scene, and so we would play a lot of blues numbers at clubs…. But whenever we’d play a soul tune like ‘Mustang Sally’ or ‘Soul Man,’ everybody would get up and dance—it was mayhem. And when we’d go back to playing blues everybody would sit down. And I thought if I played soul music all night, people would dance all night…. If I could play this music with a big band, I’d have kind of a niche here. And it turned out to be right.” Berthiaume began looking for musicians as committed to soul as he was.

His friend, the lead singer of a funk disco band called Booty Vortex who goes by the stage name Kit Holliday, remembers it differently. She met me at a Starbucks a few blocks from the company where she is a network infrastructure engineer. Despite her impressive resume, her greatest talent is her ability to say “Booty Vortex” with a straight face. “Justin was working with a power trio that was sort of blues that went to blues-rock/experimental, and I think that he was maybe looking for something to balance that out. And maybe make some money,” Holliday says. “Because if you’re doing original experimental stuff, you know, you’re getting 30 bucks a night at Toad for each guy in the band.”

The Chicken Slacks started out small. Originally, it was just Berthiaume, his friend Mighty Slim, and a bassist named Jehu. They would hole up in the Music Complex, an old rehearsal space that’s now been divided into condos. “Us three just worked out James Brown grooves for hours,” Berthiaume says. When their first lead singer, Big Daddy Dave, joined the group, they rehearsed and bonded for a year before they had their first gig.

Though one year may seem an excessive amount of rehearsal, the group has always been built on dedication to the original material and workmanlike consistency. “When you’re a musician in Boston, there is a lot of switching around, and I always wanted a band that would get together every week,” Berthiaume says. “Any kind of negativity we wouldn’t really stand for. I think setting a work ethic like that and an expectation of devotion, we were able to keep a consistent quality to the show.”

In 2005, the band played their first show at the Cantab. Stephen Ramsey of the Cantab Lounge gave a suitably gruff explanation of his decision to hire the group: “You want to know about the band? Ask the customers. I know why I hired them—they’re a great band.” And if the audience’s lack of inhibition is any indication, it seems that the Cantab sells a lot of alcohol, too.

Rick Rosco, the current bassist, joined the group a year and a half after their founding and played at the first Cantab gig. Currently, he’s the most senior member of the group and one of the only members who grew up as soul was first entering the mainstream. A technical writer by day and soul bassist by night (the designation “international man of mystery” was also thrown around), Rosco embodies the group’s commitment to having both young and old musicians play together. The mix allows for the dynamic between enthusiastic discovery and fond memory, which drives the band. With a few exceptions, Rosco has played for the full length of the Cantab residency—a seven-year stretch broken only for Thanksgivings. “It’s a good feeling,” he reflects. “It just feels like coming home.”

“ANOTHER DAMN THURSDAY"

The Cantab is often called a “dive bar,” and depending on which of the three Thursday Chicken Slacks sets you hear, the term is either a romantic wish or a dramatic understatement. At 8 p.m. on Thursday, an hour before the show starts, the bar is nearly empty save for a few customers and the two bartenders, Amanda and Chris. It smells of alcohol, wood, and something disconcertingly unidentifiable. The band members trickle in over the course of the hour and greet each other familiarly. Tracy “Sweet Tea” Fontes, the lead singer, arrives with his brother. Valadez, the saxophone player and emcee, stands with his back to the nearly non-existent crowd and riffs over Sam Cooke’s “Cupid” on the jukebox. The crowd is mostly regulars, most of them old enough to know the music from their youth. As the small crowd picks up drinks and settles in at the tables, the band slowly assembles on stage. At 9:30, Jeremy leans into the mic, and with a “Hi y’all!” the group kicks into two casual instrumental grooves. Fontes lingers towards the back as the older crowd nods along. At the end of the second number, Fontes strides from the back across an empty floor as if it were the house at the Apollo and begins to belt Eddie Floyd’s “634-5789.” His voice is excellent—reminiscent of Stevie Wonder and Cee Lo Green in its odd combination of clarion high tones and pinching husk—and as he sings, the crowd grows and a few younger patrons begin to dance. The band’s music tightens around his performance. By the end of the first set, the bar is packed.

Each show is a strange combination of new and old. The Cantab has a cheesy clock on the wall, which looks as if all its numbers have fallen off the face and collected at the bottom of the frame. “Who Cares?” is written across the middle. The bar on Thursdays seems outside of time—the music is from decades ago, the band spans generations, and the young and old dance together.

Reavey reflects at the end of the night that the three sets were practically different shows. The first was a pleasant experience shared with an older audience: the group breezed through laidback numbers like “Groove Me,” “It’s Your Thing,” and “You Send Me.” But by the time they began the second set, a college Halloween party recently exiled from a nearby bar had arrived, and the Cantab was so packed with superheroes, half-naked police officers, princesses, and aliens that grinding rather than twisting became the norm. Slowly, the older patrons were pushed to the fringes as the college students initiated an almost orgiastic tone. The group played without flagging as they fed off the energy of the crowd, but you could hear the frustration in their pleas that the crowd try to dance without breaking any of their equipment. At one point, Fontes punctuated the saccharin lines of “My Girl” by begging the front-row crowd to make space while a young man in garish suspenders thrust his hips suggestively at an older woman. The third set became even rowdier, but about halfway through, most of the audience dispersed and only around 20 dancers remained. There was a sudden calm during the last numbers—“How Sweet It Is To Be Loved By You” ended with Fontes addressing the last stragglers: “Congratulations, you’re the group that didn’t get thrown out.” After an encore of “Shout” for a crowd of 15, the bar cleared out.

The band tolerates even the rowdiest crowd, and it seems to be an integral part of their larger mission of preserving soul music and a successful fulfillment of their more practical goal of making sure everyone enjoys themselves. “We provide entertainment so people can have a good time and dance and enjoy this music that stood the test of time,” Rosco says. “That’s what we really do.”

This combination of soulful ambition and day-job commitment keeps each show at the Cantab fresh and meaningful for both the band and the audience of regulars. There’s an embracing tolerance in Valadez’s gleeful, rapid-tongued emcee monologue: “This is another damn Thursday.” Somehow, he uses the same voice even when he asks the crowd to be careful not to break Fontes’s foot.

THE SOUL SURVIVORS

“Maybe the drunk college kid crowd tweaks the show a little bit, but even that’s genuine,” Berthiaume says. “That timelessness that’s in the music is in that scene.”

Though the music may be timeless, many acts devoted to the same genres resort to gimmicks to make it feel authentic, a paradoxical strategy. The Chicken Slacks have some of the typical aspects of a traditional cover band—the nicknames, the hype man—but their sheer skill and overwhelming commitment to the Cantab make genuine the crowd’s experience of their act. Their shows are fueled by tenacious showmanship verging on willful ignorance of their ever-varied surroundings, and a throbbing energy that feeds on the rowdiness of the crowd the band tries both to tame and entertain. All of the members treat their work in The Chicken Slacks like a job but maintain a belief in the music that transcends their routine.

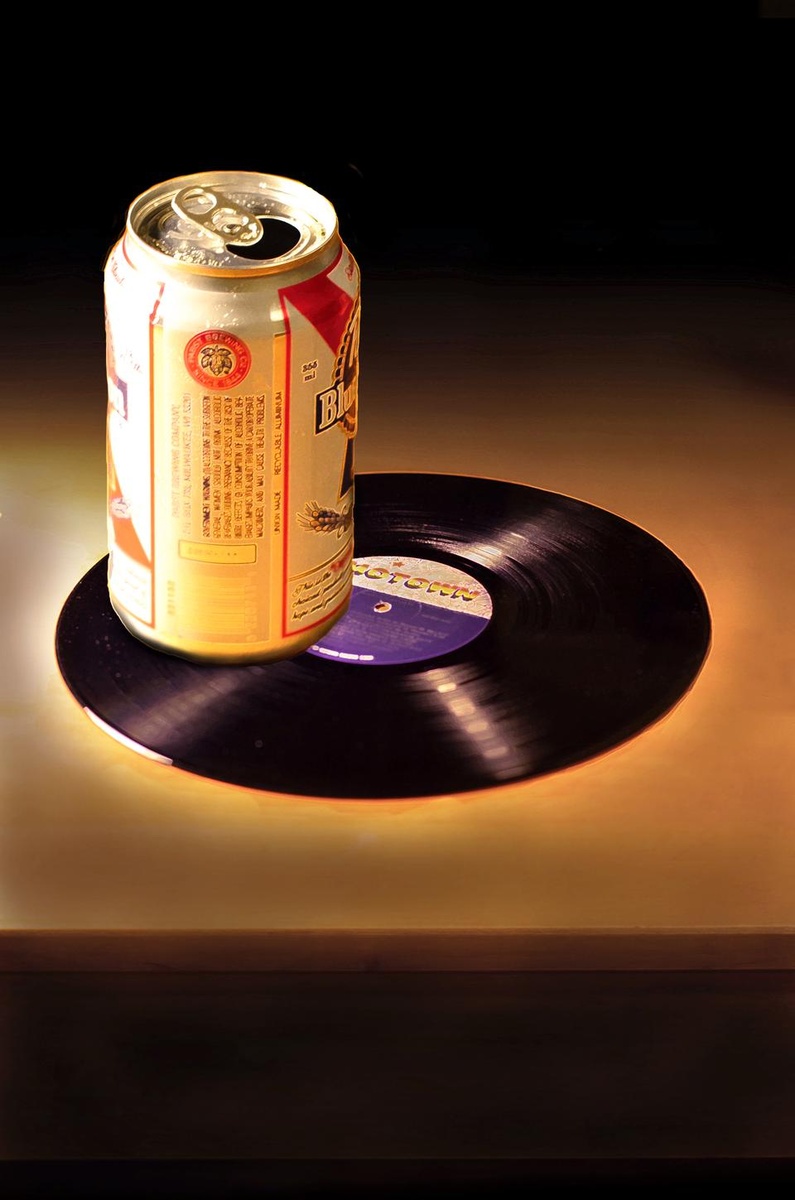

Soul music, even in its original form, has mostly been played by cover bands. Many soul and Motown greats would cover each others’ songs, which in turn were often written by songwriting teams. With the exception of singer-songwriters like Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, soul and Motown music has always been sung by thrown voices; snatches of melody and refrain that come out of the dancehalls, into the mind of a songwriter, and back into the dancehalls and bars through the voice of a singer. So when Valadez talks about “putting a little Chicken Slacks into it,” he and his band are essentially doing the same thing with their arrangements that the ‘original’ artists did. Only they are working decades later and most frequently in a bar where high-definition is something that comes with a channel in the 800s rather than off a vinyl cut from more wax.

Each member of the band thinks of soul music as an ideal genre for different reasons. Berthiaume sees soul as spiritually consistent with its gospel roots: “Originally this music was singing and dancing for God, and then Ray Charles just kind of switched that a little bit and instead of ‘This Little Light of Mine’ it became ‘This Little Girl of Mine,’” Berthiaume says.

For Rosco, The Chicken Slacks are a means of preserving the music of his youth. “It’s music that I grew up with, I listened to it as far back as I can remember,” Rosco says. “More recently with The Chicken Slacks I’ve been able to go back and revisit the material that I grew up playing and I hear new things in it, and I hear more authentic bass lines, so I’m enjoying it a second time around as well.”

Valadez talks about his work with The Chicken Slacks through the lens of his training as an expressive arts therapist. “I knew the power of healing in music. It does have that power to heal the individual or at least set them in the right direction when used properly,” Valadez says. For him, the music loses some of that power on record, and only in a live setting can it really move a person physically and spiritually.

Fontes sees the same value in the music. “I think when you sing soul, you’re talking about things people have in common. I think it can be therapeutic for a lot of people,” Fontes says just before the show. “The songs I like singing the most are the ones that talk to people where they live their feelings.” Even when he has to keep the crowd back, he can remember why he plays the weekly concert: “That anticipation and excitement builds in me every week.”

“That gig can become a slog,” remembers Berthiaume. “You gotta love it to do it…but I love that place—it’s the best place in the world. There’s no bar I would rather be at.”

But eventually, the shows did wear on Berthiaume. “Once it stopped being fun I didn’t want to do it anymore. I wanted to leave before I got sick of it, before I got jaded. At the same time I was sweet on a girl,” he remembers. “I wanted to spend time with her. We wanted to go on an adventure.” Still, he occasionally comes back to see the group he began 11 years ago. “Sometimes I’m excited and feeling good and I’ll play a whole set, and sometimes I won’t even play because I love to sit back and watch the whole scene—I never got to do that for so long.”

I ask Berthiaume about what he thinks of what he sees from the back during the rowdy sets and the quieter nights. “I see joy,” he replies. “It’s joyful.”

—Staff writer Benjamin Naddaff-Hafrey can be reached at bhafrey@college.harvard.edu.

Read more in Arts

Taylor Swift Gets Even More Poppy But Keeps Passionate Narratives