I’ve picked the wrong time to be walking across the Yard. It’s 1 p.m., and students leaving class are clogging up all the walkways. I rush past one girl who is in the process of disentangling her headphones, and slide around a pair of men who are walking side by side but in silence, as one sends a text message on his phone. I spot someone I recognize and wave, but his headphones are in and his head is down.

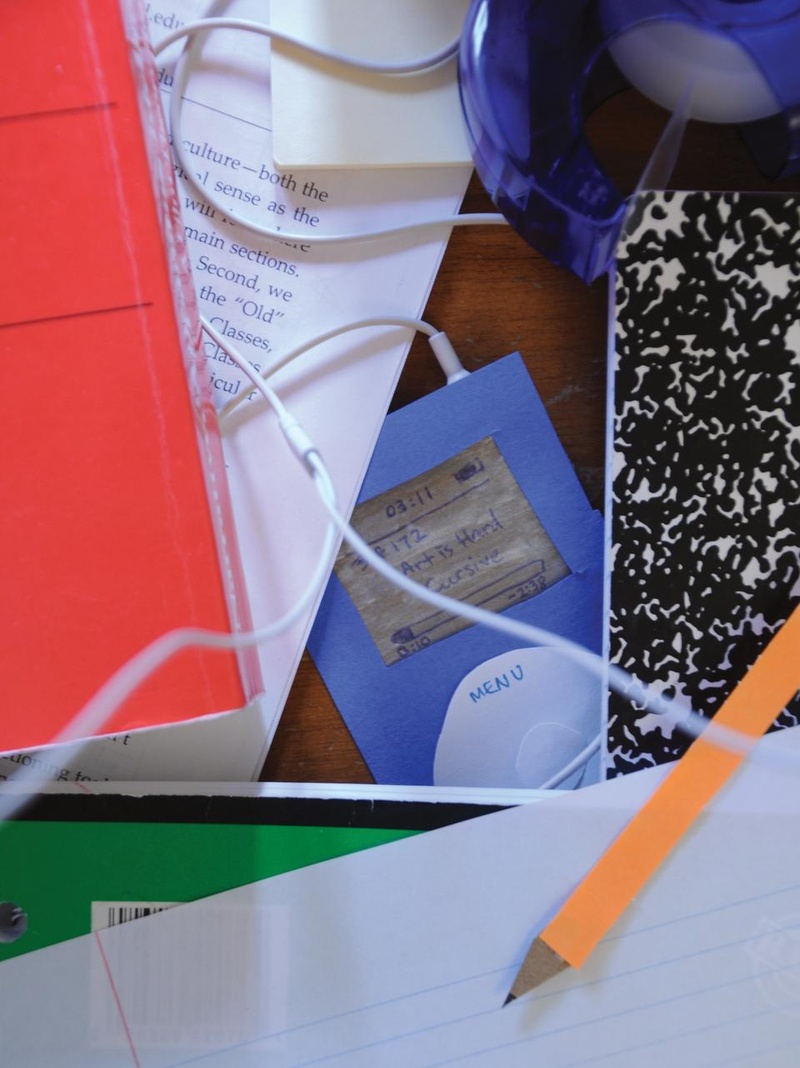

The sight of the detached and plugged-in is all too common on Cambridge streets. First introduced by the Walkman and universalized by the MP3 player, portable music-playing devices have shifted the function of music for a new generation. A corresponding backlash has occurred against digital music, as music aesthetes have sought older listening media for higher sound quality and perceived authenticity. With most music players of the past now easily accessible, well-defined camps of listeners have emerged based on disagreements about the merits of each system and, by extension, about the purpose of music itself.

REVINYLIZATION

After passing many more tuned-in men and women in Harvard Square, I head down JFK St. to meet Planet Records owner John Damroth. Planet Records is packed with CDs, vinyl records, and concert DVDs, and jazz reverberates throughout the store. The Harvard Square Planet Records opened in 1997 as a second branch that would sell only CDs in an attempt to capitalize on the new industry. When the original Kenmore Square store burned down, Damroth was forced to move all of his vinyl to his new location.

Carrying records was a major drawback in the early 2000s. “In 2005, we were lucky to sell a couple of records a week,” Damroth says. “Records took up too much space, and if they weren’t being sold, there was no room to put new ones out.” It seemed like vinyl would stifle itself under its own weight. But much to Damrothe’s delight, record sales recovered about three years ago, to the point where they now make up a third of Planet Record’s total sales.

Damroth isn’t surprised by vinyl’s revitalization. “It’s a different listening experience, where you’re much more connected to the artist,” he says. For Damroth, listening to vinyl is a physical project. “You put on side one, and then you have to flip it over for side two. You have to actually touch it. You can look at the artwork, which is no small thing.” Since a record requires much more effort that a CD, the process has a way of making the listener more engaged in the music. He flips on Run-DMC’s eponymous debut, released on LP in 1984, and immediately starts nodding his head and singing along.

Record appreciation has created its own self-contained community at Audio Lab in The Garage. Most customers wander in and out, examining the frontline speaker equipment. A couple of men stay sitting in chairs, neither customers nor employees, but self-professed music lovers and friends of store manager Mike Volpe. Together, they reminisce about the fabled jazz musicians they’ve seen in concert over the years. Charles Ryan, a Medford resident who describes music as his “church,” has spun many memories out of the vibrations of a record. “Two or three people would come over, sit on the floor, and just listen to an album,” he recalls. “Music was the central thing. Now, there are so many gadgets that take over people’s attention.”

The sound quality of vinyl also played a large factor in sparking Volpe’s and Ryan’s enthusiasm. “Analog has more detail and warmth. It’s more musical,” says Volpe. Although he admits that digital music from quality speakers can compete with its analog counterpart, he still feels that something about digital sound is off.

“The fact that young people are going back to turntables is an indication that something is missing from the digital world,” says Ryan. “There has to be something that’s reaching inside on a personal level.” I exit the store, leaving them to continue an extensive conversation about Billie Holliday, Bill Evans, and Paul McCartney’s guitar player.

SOCIAL LISTENING

At the Audio Preservation Studio on Garden St., Dave Ackerman and his fellow sound engineers are in the process of trying to salvage rare and fragile recordings and convert them to digital for Harvard students and faculty. The studio’s equipment collection is nonpartisan in the technology war: turntables sit next to cassettes, CD players, eight-track reels, and computers. Ackerman is well-equipped to explain the sound quality differences between the various music players, and he is quick to repudiate the idea that vinyl has an inherently better sound. “Digital recordings are a very good approximation to the original,” he says. “Most people would be hard pressed to notice a difference.”

Ackerman explains that the bad reputation that digital music gets for its sound quality comes from a rushed shift to CD in the 1990s. Record labels, in an effort to jump ahead of the curve, remastered old recordings as quickly as they could. They often simply transferred the original master tracks to the CDs, not realizing that the resulting sound would be different. “The masters were tweaked to be as good as possible for a record. The CD doesn’t have the same physical characteristics,” says Ackerman. Early digital converters were especially poor, but Ackerman says that digital sound has mostly caught up with analog. While analog tapes wear out over time, the digital copies that the studio makes preserve historical recordings for future music enthusiasts.

But although he finds the sound quality argument less compelling than the denizens of Audio Lab, Ackerman still sees a unique value in vinyl. He, like Ryan and Volpe, would listen to music on vinyl as an activity in itself, which Ackerman believes fosters an enhanced social skill he calls “active listening.” “When you train yourself to pay attention on that level, it’s a different form of consciousness,” he speculates. “When people aren’t trained to do that, their social patterns and behaviors become more self-centered and a lot less engaged in the world around them.”

As I exit the studio, I suddenly feel a deep distaste for the headphones in my pocket. Each sighting of a pair of earbuds makes me more and more uncomfortable. Is appreciation for music diminishing because of how easily it can be procured? Could I possibly be contributing to the decline of social interaction?

DEMOCRATIZING SOUNDS

Read more in Arts

Newcomers Wormald and Hough Look to Break Out in ‘Footloose’ RemakeRecommended Articles

-

ICA's "The Record" is Nostalgic for VinylAs a whole, the ICA’s presentation is limp and witless, too bogged down with shallow nostalgia to present a potent argument for the importance of vinyl.

-

Top Ten: In your Ear RecordsTop ten staff recommendations from "In Your Ear Records" an independent record shop on Mount Auburn Street.

-

Mind the SeamsCareer portals and dating sites flourish precisely because they work—not by replacing human intuition and pattern recognition, but by broadening our horizons and suggesting opportunities that might have been lost in the welter of our modern minds.

-

Institute of Politics Continues to Increase its Social and Digital Media EffortsAfter two years of revamping its virtual presence, the Institute of Politics will launch its latest social media initiative next week to better connect undergraduate members with students beyond the Institute.

-

Ivy League Digital Network Launched Last WeekendThe new online network, which livestreams athletic contests from all eight Ivy League schools, premiered this past weekend with the showing of 23 live events.

-

The Internet is Yours, So Protect ItYou’ve grown up with the internet, developed alongside it, and stored a significant amount of your lives on it. And now you know that they, the NSA, are collecting your stuff, your information—not rightfully theirs, but rightfully yours.