“Who is the anti-Semite?” asks Jean-Paul Sartre at the beginning of his 1946 book “Anti-Semite and Jew.” Sartre answers: “The anti-Semite is someone who hates himself.” Sartre goes on to argue that there is no such thing as ‘the Jew,’ in essentialist terms. It is not the Jew who engenders anti-Semitism, but rather the anti-Semite who creates the Jew, searching for an object of hatred. Sartre’s thesis is a problematic one, as it suggests that Judaism and Jewish culture are devoid of actual content, and yet it is one that is understandable in the wake of the Holocaust. Since then, however, the way that we think about anti-Semitism has changed.

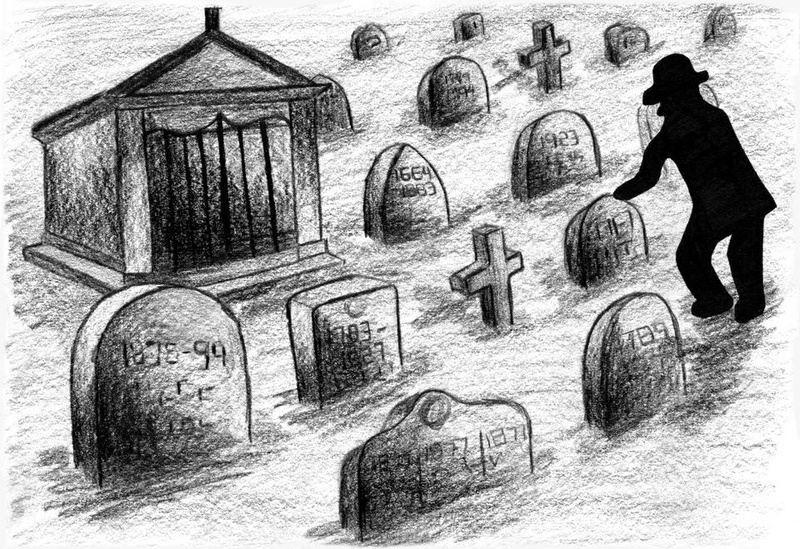

Or has it? Umberto Eco’s latest novel “The Prague Cemetery” tells the story of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a document first published in Russia in 1903 that falsely described a Jewish plot for world domination. The text was used as an excuse by the Nazis for their systematic genocide of Jews, and it continues to be disseminated today by anti-Semites around the world. Eco’s investigates semiotics—the study of signs and their relation to the objects that seek to represent—and is postmodern in nature, often referring to “the Narrator” and “the Reader.” This choice is perhaps unsurprising given that Eco is one of Italy’s most prominent semioticians. Importantly, he emphasizes in his preface that the novel is based entirely on real events. He writes: “The Prague Cemetery is a story in which all of the characters except one—the main characters really existed. Even the hero’s grandfather, the author of a mysterious actual letter that triggered modern anti-Semitism, is historical.” To further underline the historicity of the text, Eco makes use of illustration, which also ties into his interest in exploring different types of signs. Interspersed throughout the text are 19th-century prints coupled with captions drawn from the text of the novel. The final page is a reproduction of the cover of the first Russian edition of “The Protocols.” Although ‘the Reader’ never expects subtlety in this kind of novel, the complete lack thereof in “The Prague Cemetery” renders it neither thought-provoking nor enjoyable.

Eco traces the story of the fictional Italian Simone Simioni, who grows up in Piedmont just before the unification of Italy, and ultimately helps pen “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” His grandfather was a virulent anti-Semite (and, as Eco reminds us several times, a real person). Simioni, inheriting his grandfather’s obsessive hatred of the Jews—“I dreamt about Jews every night for years and years”––experiences some of the most significant events of the 19th century in Italy and France, using them all as opportunities to besmirch and persecute Jews. Simioni lives through the Risorgimento, the Paris Commune, and ultimately the Dreyfus Affair; the novel suggests that it was Simioni himself who framed Dreyfus. The personal drama that fuels the narrative is Simioni’s own confusion about his identity; the novel opens with Simioni unsure of what has happened to him or who exactly he is. The story is partially told through letters between Simioni and the mysterious Abbé Della Piccola, who seems to live in Simioni’s apartment and can recall certain facts that Simioni has forgotten. Each man considers that they might be the same person, but quickly dismisses this possibility. I do not think that it spoils the book to say that they should have trusted their intuitions. In the middle of the novel, ‘the Reader’ learns that Simioni once murdered an Abbé Della Piccola who got in the way of his latest anti-Semitic project. Eco’s use of Piccola as Simioni’s alter ego is a means of exploring ‘the Other’ that exists inside of us all, the very same notion that Sartre addressed in his 1946 work. Toward the end of the novel, ‘the Narrator’ tells us: “It was time to accept that the Other did not exist. The diary, moreover, is a solitary entertainment. He had, however, become accustomed to this monody and decided to continue. Not that he felt any particular love toward himself, but his dislike of others induced him to make the best of his own company.” Indeed, the amnesia that Simioni experiences is precipitated by a sexual encounter with a woman of Jewish origin, when he is dressed up as Della Piccola ostensibly for reasons of subterfuge. After the trauma of recognizing his attraction to a Jewish woman, Simioni is unable to distinguish his true self from his false identity as Della Piccola. He has to split himself from his internal ‘other’ as a means of suppressing it.

However, the split personality’s role is more complex than simply revealing people’s secret and subconscious selves. The trope also allows Eco to explore the role of the signifier itself. Early on, Simioni reveals that he likes to dress up as others: “what I most enjoyed was appearing to be someone else; the thought that people had no idea who I really was gave me a sense of superiority. I had a secret.” Like a costume, a sign is a representation with multiple layers, which can only be read by those who have the tools to understand it. This logic is also crucial to understanding Eco’s interest in the genesis of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” which is, after all, a false secret text, full of signifiers that must be measured for their authenticity. But while the concept has merit, Eco’s reduction of European anti-Semitism in the 19th century to a historical novel about donning another’s robes ultimately fails to do justice to the topic. Despite his deep awareness of semiotics, Eco’s own representation of historical truth is ironically too simplistic to pass muster.

—Staff writer Sofia E. Groopman can be reached at segroopm@fas.harvard.edu.

Read more in Arts

Portrait of an Artist: Matthew M. Lombardo and Charles L. Busch