Jody Cukier Siegler ’79 is the type of person who, when asked if she minds being recorded during an interview, says, “Just as long as you don’t give it to, you know, the House Un-American Activities people.” She is the type of person who says things like, “Are you sure you want to know about this?” Or, “So that’s kind of what I thought when I got there, in 3,000 words or less.” Why she’s still in California, even though she grew up in New York: “I’m being held hostage here by my husband who adores the climate.”

Or: “I was never culturally prepared from my time at Harvard how extraordinary and mind-bogglingly fabulous being a mother and running a family would be.”

Thirty years ago, before family, jobs, and graduation, Jody and her roommates got a letter, early one morning, saying that they’d be living in Mather House together for the next three years. It was the worst thing that could have happened to them, some of them thought: Mather with its new architecture and ugly towers. You had to walk so far to class. Their seventh choice out of twelve. But it all turned out fine, they said—they loved it. Things worked out.

Today is Housing Day at Harvard, which is about where you will live for the next three years. It is also about you waking up, tired and still half-drunk, realizing that the people opening the letter in those chairs across the room are going to be “your college roommates,” the ones that you’ll tell stories about when you’re older, the godparents to your kids, your aging links to youth and beauty. You’re stuck with them, for life, whether they’re a part of your life or not.

Jody is speaking on the phone a continent away, somewhere near Los Angeles. She might be sitting in a chair in her dining room. A land phone rings every once in a while and she pauses to see the caller. A dog barks in the background. In the middle of speaking about a roommate in New York she ushers her husband pleasantly out the door: “He’s looking longingly at the kitchen counter like, ‘Can I get lunch today or is that a lost cause?’” She settles in and keeps talking.

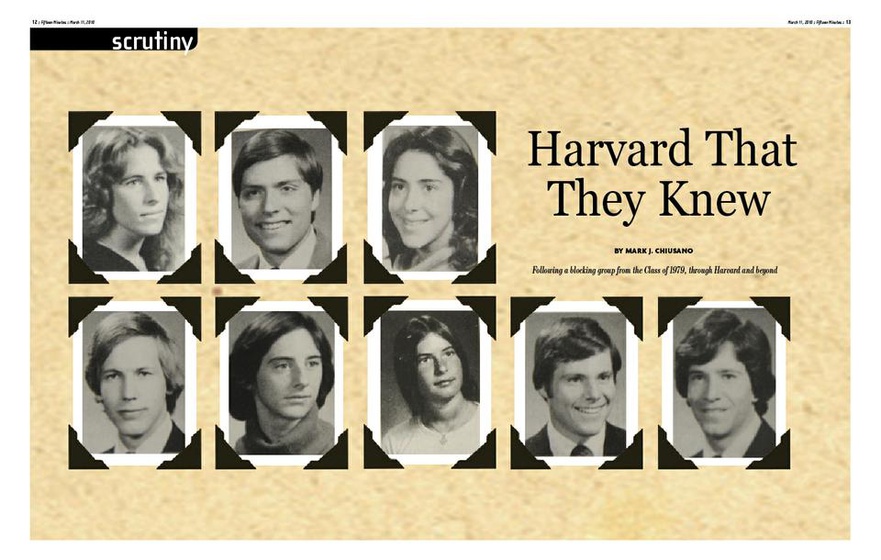

She had a big rooming group—their era’s equivalent of a blocking group—and she’s going through them all: Claire, Carole, Susie, Leslie, and the men—Mike, Tim, Ed and Jim. Thirty years ago they were in Mather, sharing a bathroom door—it had a lock. Thirty years ago Jody was a coast away, time stretching like land in front of her: this is what she talks about, curled up with phone neck-and-shouldered, legs crossed, making sure her interviewer is still interested every once in a while—“Am I rambling? No? Oh okay good!”—sounding genuinely surprised every time I’m still there.

AS IT WAS

In the 1970s, when Jody and her rooming group were at Harvard, their school, like the rest of the country, was tired. The Sixties had been exhausting. They began conservatively enough, with 2,000 students gathered in front of Widener on a spring day in 1961 to register their displeasure at the abandonment of the handwritten Latin diploma. In April of 1969, protestors took over University Hall. Faculty members prowled the outside of Widener Library, protecting against fire-bombers. Someone wrote on a physics blackboard: “no class today, no ruling class tomorrow.”

In his book, “The Harvard Century,” Richard Norton Smith ’75 writes, “Battered by Vietnam and Watergate, drained by inflation, adrift under commonplace leadership, Americans turned inward in the Seventies. So did Harvard.” The sheets of protective plastic hastily thrown up over the windows of the president’s office in ’69 were still there, but they never needed to serve their purpose. Government professor Stanley H. Hoffman said about the student body, “They have the bizarre notion that a university is for studying.” David C. McClelland, a Harvard psychologist, made a name for himself selling theories about human behavior to government agencies and corporations. “In the Sixties, if you said ‘business,’ people spat on you,” he said. “Now I’m a hero.”

In a final gasp of giving in to liberal Sixties sentiments, the Seventies were also ultimately home to the final joining of Harvard and Radcliffe—in the spring of 1975 students were admitted to both colleges by the same committee. In the fall of 1975, Jody and her roommates came to Cambridge.

This was the era of disco, of Earth, Wind and Fire and the Commodores. Jody and the others had record players in their rooms. They threw parties and jazz concerts in Mather courtyard. When the weather was nice they would run power-cord extensions out the windows and type their papers outside, on their Smith Corona electric typewriters. They screened movies in the Science Center: once, during the newest 007 film, someone spliced in a hardcore pornographic scene right after the movie alluded to a Bond tryst.

This was a time when Winthrop House had an endowed fund for ice cream sundaes every weekend. It was also a time when the administration put women well inside the Yard for safety: Stoughton and Thayer rather than Wigglesworth. When one of Jody’s suitemates, Susie Case Peterson ’79, graduated, she lived in an apartment in Boston where her landlord was a heroin addict. One night he used his spare key to break into her room while she was sleeping, but she didn’t know if he meant to harm her or just rip her off. He passed out cold in the kitchen, sprawled on the floor.

On weekends, the rooming group might wander around the back of MIT and walk along the railroad tracks, throw rocks through the windows. Back then it was a wasteland of abandoned warehouses and graffiti. This was when Reverend Gomes came to Harvard (“He couldn’t have been that much older than us!”). Yo-Yo Ma ’76 was an undergraduate, and in the introductory music classes he would play examples of the pieces being taught. Vietnam was over, but lighter protests died hard: hot breakfast was gone due to budget cuts, but the so-called Egg Shell Alliance marched in the Yard and won it back.

THE GANG

Jody came from Long Island, N.Y. She would return home during the summer to get a taste of the real world, once working on the boardwalk in Wildwood, N.J., living in a two-bedroom apartment with four girls she’d never met (after being told that it sounded like “Jersey Shore,” she says, “That’s exactly what it was. Well, no, except for the guido part. It was actually a bunch of French Canadians, who I don’t want to offend.”)

But at Harvard, Jody at first fought to adapt. Her father was an immigrant Auschwitz survivor, and her mother was born and raised in Brooklyn. Neither of them went to college. “I remember her mother always used to want to come up and sleep in our college dorm,” says Claire Goodman Cloud ’79, who became Jody’s roommate. “She had never been to college, so she wanted to feel what it was like.”

Claire helped with the transition—“Claire, about as quintessential Manhattan as you can get, but not ‘that’ person,” says Jody. Claire’s father is Roy M. Goodman ’51, a state senator from Manhattan who held office from 1969 to 2002: the Statesman of the State Senate, they called him.

At Harvard, Claire was the captain of the swimming team. “I was decidedly not the best swimmer,” she says. “I was the best cheerleader but not the best swimmer.” She brought Jody along with her to be the manager.

It was Claire who brought the other girls together, gathering Carole B. Markin ’80, Leslie J. Berg ’80 and Susie Peterson Case ’79 from Stoughton. “She’s the glue,” Susie says.

The four girls lived together their sophomore year. They shared a bathroom with five other sophomores who had known each other at Exeter. The next year the group went in three separate directions: Jody and Claire stayed together, as did Leslie and Carole, with Suzie attaching herself to another group. Leslie and Carole both ended up taking a year off before graduating, and upon returning they lived off-campus.

Their class in Mather was larger than both the junior and senior classes. The class of ’79 in total was the largest Harvard had seen in recent memory. A caveat to this was the male-female ratio.

“The grad schools were nine to one, undergrad was three to one,” says Susie. “There were just a lot of men everywhere.”

“All the guys knew who you were,” says Carole. Then she thought about it for a moment. “If you were vaguely decent-looking then they knew who you were.” She remembers eating dinner and walking out and all the guys watching, heads turning.

Jim D. Auran ’79, part of the male half of the room group, was on the other side of that divide. “There just weren’t enough girls, you know? All the girls were taken after Freshman Week.”

Jim and Ed W. Harris ’79 were roommates freshman year, along with Tim E. McGee ’79. “I remember that when I first met Jim,” Ed says, “he had just moved in and I was moving in behind him and I was blown away by his amazing stereo system.” Now a lawyer in Wyoming, he is reserved but friendly: after being thanked for agreeing to an interview, he says, “Oh, you bet. Hold on just a minute while I shut my door.” Ed played alto sax in the Harvard Band, becoming drill master senior year.

As sophomores, the three men picked up Mike Ericksen ’79 and lived together in Mather for the next three years. It was as seniors that the group lived next-door to Claire and Jody, in adjoining rooms with a bathroom in between. “The suites in Mather were huge with these joining bathrooms,” explains Jim, “so you get lots of people—your rooming group became quite extended.”

Slightly embarrassed to admit that what kept him busy at Harvard was his work, Jim says, “I was trying to be an overachiever. I was doing a lot of research.” The research, into an obscure eye pigment that no one else was studying, turned into his thesis and eventually his career as an ophthalmologist.

Writing was not his forte, according to Jim. He says this in various ways: concerning the paper that he co-wrote with a colleague, who ended up writing most of it, and retelling the story of his ill-fated Crimson comp: “I’m a crappy writer.”

But 30 years since his college days, Jim seems to have become more comfortable with his words. Every five years, for each reunion, the Class Report Office at the Harvard Alumni Association compiles anniversary reports made up of biographical entries written by class members. In Jim’s 25th reunion report, he’s forced pleasantly into the medium: “[My] daughters—who each weave their magic as artists, athletes, poets, entertainers, and sprites that dance in the summer night—have enriched my life beyond my wildest expectations.” He writes with precision and poignancy of finding peace on Long Island beaches, gardening with his daughters and biking alone.

Fatherhood is far removed from a twin bed in Mather, but the two mix when the Class of ’79 returns to Cambridge for their reunions.

Reunions are things that Jim feels very strongly about, especially the 25th, the crowning anniversary of them all. “For 25 years I’ve had people tell me that the best week of their lives was their 25th reunion. I thought, well, you know, I guess I’m going to be let down.” Jim is exuberant and he starts talking quickly. “It was like going to Disney World!”

The reunions force roommates to get together. Everyone looks better, he says, more professional: the girls more mature, guys not bald yet and without paunches. You drop your car off and the football team comes and carries your bag. There is a gazebo in the Yard. The weather, of course, is always nice.

Even Leslie made it back. She hadn’t planned to go, didn’t think she fit the bill: a mother of young children, and how could she up and leave them for four days? But she did go, at least for an event or two, and she concedes that it was nice. She’s quiet for a minute and then she says, “It’s kind of fun in the moment, but afterwards, life goes right back to normal.”

Ed came back too. One of the things that he says surprised him about the reunion was how little everybody had changed, how they had the same basic personalities.

But when asked if he’s kept in touch with his roommates he answers, “No.” He pauses. “We really haven’t kept in touch very well.” It was different in those days, he says, without e-mail or cell phones, and people spread out across the continent. “I’m very sorry we didn’t because, like I said, we were very good friends. Except for my wife, they were the best friends I’ve ever had.”

Two weeks ago, Jody Cukier Siegler’s daughter died in an accident. She was 13 years old. It happened in California.

Claire and Carole were at the funeral. Claire called me some days later saying that Jody wanted to know if she could have, somehow, a copy of the recording of when we talked. If nothing else, the transcript. Jody wanted to hear what she’d said about her own daughter.

“My daughter is in eighth grade, 13 going on 14. Her primary social interactions are through texting,” Jody had said.

Also: “I feel by the hair of my chinny chin chin that family came my way, and I am so grateful and so glad that I have our daughter and our stepson: two kids, one set of stretch marks.”

Last: “For me it’s a great blended existence, if I can at all control my schedule and be a mom and be home for my daughter—it is a luxury. I feel bad for people who don’t have choices.”

Carole sat shiva with the family. She also e-mailed Leslie, who lives far away on the other side of the country, in Massachusetts. No one had seen Leslie in a long time, and she had only been at the 25th reunion for a day. The way Carole explains it, Leslie was the sanest of them all in adulthood: one career, a straight line. She’d been a professor for years.

Leslie answered the e-mail that night, immediately. Terrible, it was terrible.

THE RED BOOKS

The Harvard Alumni Association keeps copies of the Class Reports—the books with the pictures and stories of Jody, Jim and the rest—at its office on Mt. Auburn Street. There’s a doorman who nods when you walk by. Inside, the ceiling is high, an indoor arboretum, a huge open space with sleek windows letting you see into rooms on upper floors.

Inside the elevators the walls are wood-paneled, edged with brass molding. The control panel glistens, and when you touch the button—six—that’s the first fingerprint on the whole thing.

Exiting the elevator, inside the office proper on the far wall, there’s the Harvard Alumni Association sigil. It’s a huge shield with the letters “HAA” on top and, below, a depiction of a road that narrows to a point, as if far in the distance. The wall decorations are sleek.

There’s a table with four chairs arranged symmetrically around it where they’ve laid out magazines and the recent class reports, heavily stacked.

“Careful; those books can suck you in,” the secretary says. She has a British accent and a phone balanced between her cheek and shoulder.

The regular class reports for the regular reunions—fifth, 10th, 15th, 30th—are Cornell red, paperback, with cardboard covers porous to the touch. But the 25th Anniversary Report is colored crimson, its titular letters in gold trim, the twin shields of Harvard and Radcliffe embossed on the front, raised a little so you can feel them if you run your hands over their rims.

The 25th Anniversary Report is the pride and joy of its makers. It is hardcover. Its pages are glossy. It has pictures—sometimes before-and-afters—next to names, sometimes with large bifocals, crazy haircuts, moustaches.

There is a lot of “life has been good to me.” Someone says, “I enjoy the fribble.” And “I feel extraordinarily grateful for the past 25 years.” There is Kimberly C. who goes on for pages and pages: “On some levels, I am exactly where I thought I would be at this point in my life.” There is David C., whose entire entry reads, “LAST KNOWN ADDRESS: XXXX Fox St., Riverside, CA.” It has a picture from when he was younger, hair wavy and unruly and parted where his nose meets his forehead.

The book is reunion on paper. Everyone is here. Everyone is smiling. It is easier to see old friends like this than in person, by a sickbed, at a funeral. Their pictures are paper playing cards, gathered as if nothing has changed.

Jim had said about “The Red Books,” as the Class Reports are called, “If you ever look through them, it’s like they’re the Book of Life. They tell all these anecdotes. I’m always exhausted staying up all night reading them.” It’s true: the books hold everything in them about the alumni experience. What it means to find the world. What it feels like to be mediocre, or not. Above all, the process of growing distant.

“That’s kind of what you get when you read them,” Jim says. “Just like talking to old farts like me.”

Ed’s entry is simple—just the biographical details. He lives now on a place called The Alleged Ranch. He was born in Loveland, Colo. He does have before and after pictures, and they are set up in the same way, head inclined in the same direction.

Jody’s page starts characteristically: “When I got pregnant and I was told that my blood type was A-, I asked the doctor what held him back from giving me an A+.” Later: “I graduated from Harvard in 1979 B.C. (Before Computers).”

Then she talks about her daughter, how she became a born-again mom. She says the young girl is a brightly shining beacon of love.

She ends with these words: “I could go on, but who would want me to?”