Long before making his way to Baghdad, Carlson was familiar with the ethical questions faced by journalists struggling to remain balanced as they report on the chaos around them. In 1969, he stood with Harvard’s radicals as they barricaded the doors to University Hall, snapping pictures as the students ransacked Faculty files. When then-University President Nathan M. Pusey ’28 called in the police—whom Carlson describes as “looking like gladiators” as they came in at dawn carrying sledgehammers—Carlson witnessed classmates being beaten and went along with the conquered occupiers to jail.

He says that he was allowed to leave his cell when Harvard was notified that he was covering the takeover for The Crimson, but on the condition that his film be confiscated. Carlson gave authorities an empty roll and proceeded to sell his shots to Life magazine and the Associated Press.

Several of his Crimson colleagues were in the University Hall crowds that spring—some of them as reporters, some protesting themselves. James K. Glassman ’69, who was The Crimson’s managing editor the year before the takeover and away doing thesis research during it, wrote in Harvard Magazine a few years ago of his decision to abandon the shield of journalism and declare himself an “obstructive demonstrator” at an earlier sit-in. For punishment, Glassman explains in that article, he was put on probation and prevented from printing his own name on The Crimson’s masthead during the first semester of his tenure as managing editor, though a charitable dean allowed him to remain enrolled at the College and hold that office.

But asked on which side his allegiances fell during those turbulent years, Carlson pauses for a while. At last, he mentions the profound effect that the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy ’48 and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had on him in 1968, then goes on to talk about his father and uncle, both veterans. He came to oppose the war in Vietnam vehemently, but says he still retained a great respect for the military.

Ultimately, Carlson says his journalistic aspirations guided him to the middle of the road in a polarized time.

“I wasn’t as absolutely sure as a lot of other people,” he says. “But I was absolutely sure that I wanted to be there to record the best and worst passions of my generation trying to do something.”

Split-Second Exposures

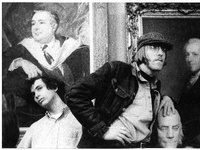

Three and a half decades later, Carlson still remembers the composition of those University Hall photographs, one of which he says was “like a Renaissance painting” that he happened upon as it formed for a moment in the Faculty Room.

Another of his best images—the two students and Benjamin Franklin’s statue—he says was captured after belatedly realizing that he had wasted three hours shooting without any film in his camera.

“I saw this thing aligning,” he says. “I held my breath and shot an eighth or a fifteenth of a second…It just was electric.”

Carlson describes a much more painstaking process as he and Katovsky assembled Embedded last spring: the interviews in Iraq plus several more done by phone from the United States, a painstaking editing process, writing an introduction to each chapter, arranging the interviews into a coherent whole.

“We actually thought of it like music,” he says. “We would reorder [the text] so it had the form of an arc of conversation, an arc of emotional moment.”

But Carlson says their attachment to neutrality did not keep him and Katovsky from putting their own imprint on the text.

“There is an authorship there,” he says. “People who are compilers are people who take already-written pieces and put them in order…We were out there in the field, doing the midwifery.”

—Staff writer Simon W. Vozick-Levinson can be reached at vozick@fas.harvard.edu.