April 9, 1969: Michael Kazin ’70, co-chair of the Harvard chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, stood in University Hall with his hand raised after students took over the building.

Thirty-five years and a week after Timothy G. Carlson ’71 brought his camera into an occupied University Hall, the snapshots he took there can be found in magazine archives or a skip-filled CD-ROM. Still, no number of scratches or fading decades can obscure the behind-the-scenes images of the moment the ivory tower became a battleground.

In one mid-range photo, light streams through the elegant windows of the chamber in which the Faculty of Arts and Sciences meets periodically, though this is no normal Faculty gathering. We cannot see who presides over the forty or so radical students packing a corner of the room they have taken by force, but it is certainly not a dean. They wait eagerly and a little uneasily as several raise their hands, one standing tall, in a meeting Carlson now compares to the Paris Commune, “reinventing history from the moment.”

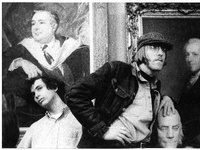

Another of Carlson’s shots has only two living figures, dancing awkwardly with two ghosts of Harvard’s past: one student rests a jaunty hand on the bald pate of the Faculty Room’s bust of Benjamin Franklin, while another’s skull seems in the process of being tickled by the two-dimensional knuckles of the bygone Harvard don whose portrait hangs above him.

Carlson took these pictures of his revolutionary classmates at the height of the College’s April 1969 student takeover, when he and a handful of his photographic subjects were Crimson editors, right in the middle of the chaos they were reporting on. The images are full of the uncertain immediacy of that time, that tentatively-toed border between politics and personality, youthful rebellion and major social change, and they were enough to get the young photographer noticed.

The snapshots Carlson took of not-so-civil disobedience ended up appearing first in the widely-read pages of Life Magazine, he says, and soon he was traveling to observe Palestinians in Lebanon as a freelance writer and photographer. With any luck, it seemed, Carlson stood on the brink of a successful career as an overseas photojournalist covering some of the most harrowing and important stories in the world.

“It seemed like a natural progression,” Carlson says now. “Perhaps I felt untouchable.”

And then his course veered. Prevented by an unexpected illness from covering the 1974 conflict in Cyprus, Carlson found himself freelancing and taking quieter domestic assignments over the decades—at a bureau of TV Guide or at the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, which went out of business while he was writing for it. Through much of the 1990s Carlson covered endurance sports for publications like Triathlete magazine.

A year ago, Carlson dropped his projects at Triathlete to go abroad again—to Baghdad, where the United States was waging its most controversial war since the 1970s. There, in the weeks before a sign reading “Mission Accomplished” was strung up behind President Bush on the USS Lincoln, Carlson conducted a series of meta-interviews on his own, speaking with journalists from a wide range of news organizations about the thrills and trials, dangers and dilemmas of reporting live on the war.

Carlson estimates that the resulting oral history—Embedded: The Media at War in Iraq—has sold more than 10,000 copies since its publication in September, winning reviews in The New York Times, the Washington Post and other high-profile venues. (The Times, generally favorable, said the book’s “accounts crackle with immediacy,” while the Post spent most of its double-bill review riffing on a BBC editor’s recently-published memoir.) Embedded has not been a blockbusting bestseller, but after bringing Carlson and co-author Bill Katovsky a Goldsmith Book Prize from the Kennedy School of Government’s Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy last month, the book is poised to bring the man who once eluded police to get The Crimson and Life magazine photographs of a campus under siege back to the national stage.

Portraits of the Artists in their Youths

It cannot be easy to summon terms to match the places and times where the world’s great ideological clashes have broken out into violent action. Carlson has faced that unenviable task in Cambridge and Baghdad, two instances that are only barely comparable, but which have led him to the same descriptive strategy of metaphor.

In conversation, Carlson is very fond of employing slightly incongruous analogies to revive these vivid memories. The words of New York Times Baghdad Bureau Chief John F. Burns, whose meditation on the ethics of reporting from a totalitarian regime forms a centerpiece for Embedded, are compared to the works of Shakespeare and the Old Testament in the book. In person, Carlson reflects that Burns sounded a lot like Winston Churchill—or was that Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg? Newsweek reporter Scott Johnson’s recollection of being shot at makes him, in Carlson’s words, something like a latter-day Stephen Crane. An Al Jazeera correspondent with a fastidious dedication to fairness is, somewhat jarringly, just like Felix Unger of “The Odd Couple.”

There was a time when Carlson saw himself and his classmates in such outsized, metaphorical terms. Concentrating in Visual and Environmental Sciences—“I finally ended up there because I could get academic credit for the pictures and movies,” he recalls—Carlson studied the great 20th-century photography of Robert Capa, Larry Burroughs and Henri Cartier-Bresson, hoping some day to follow them in documenting breaking tragedies for the rest of the globe.

Carlson attended Harvard at a time when it seems to have had a particular knack for turning out journalistic stars. He was an assistant photography editor for The Crimson at the time of the takeover, and at various points during his time there, noted critic and New York Times Associate Editor Frank H. Rich ’71 was The Crimson’s editorial chair and Atlantic Monthly National Correspondent James M. Fallows ’70 was its president. Slate.com founder and former New Republic editor Michael E. Kinsley ’72 was The Crimson’s vice president, and technology maven Esther Dyson ’72 an active Crimson editor and a friend of Carlson’s.

Today, these one-time colleagues have become their own elevated points of reference for a new generation of ambitious Harvard students—it is their names on the lips of undergraduates with their eyes on newsprint history.

Read more in Arts

Why Do I Keep Super Sizing Me?