UPDATED: October 23, 2014, at 11:31 p.m.

Goddamnit did I want everything: brown leather heels and quotes from “Ulysses,” endless red lipstick, and sex. Sex especially. At eighteen, I thought the feminist revolution had happened. You ever had a morning when you can’t even enter Annenberg without tripping over like three people whose genitals you’ve interacted with? That was my freshman year. But there was always something funny about those breakfast run-ins: Very few of them involved eye contact.

Not everyone has sex, not everyone wants sex, and not everyone is involved in hookup culture—that nebulous set of norms surrounding unmarried eroticism. Hookups are defined in a lot of ways, but to my Expert Lady Panel, “hookup culture” is a terrain of sexual activity characterized by sex outside of a nominally formal romantic relationship. It’s also characterized by a lot of boring think pieces: Hookup culture is bad for women because oxytocin. Hookup culture is good for women because empowerment. Woman is not a stable subject because poststructuralism.

I’m interested in hookup culture as a site of sexual politics, as a space where a lot about gender and power gets hashed out. And I’m interested in hookup culture as a grounds for constructing a different kind of sexuality: A sexuality with compassion for vulnerability. A sexuality that aims for justice. I want my sex hot, and I want it kind.

Cut back to freshman year. Crossing paths with last night’s hookup in the servery, I can see him looking at everything but my face. At the seasonal gourd display. At the breakfast pizza. Ten hours ago, I was blowing him. Now, he doesn’t know my name. What’s up with that?

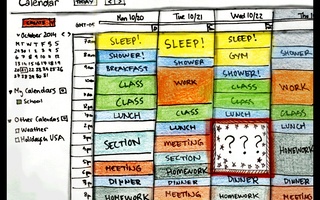

First, awkwardness. We’re trained to associate sex with “awkward,” a social performance that comes from being taught that the erotic is the weirdest and most important process of identity formation there is (it isn’t). But there’s something else going on here, and it has to do with feelings. Hookup culture is often a competition to see who can feel less. Because feelings are scary, but most of all, because we’re taught that feelings necessitate other things—exclusivity, commitment, major renovations to our Gcals. Either, the cultural script goes, your partner is a walking sex toy, or you want forever/marriage/babies. We’re freaked out by the stuff in between. With that kind of binary system, there’s no space for kindness. And this falls along gendered lines: If women have feelings we’re needy; if we don’t, we’re sluts. If men have feelings they’re weak; if they don’t, they’re players. Gay men are supposed to want to fuck without commitment, and lesbians to bed down. We all know the stereotypes and we’re all so boxed in by them that it can be next to impossible to know—much less communicate—what we want.

Freshman year, I hadn’t gotten the memo about feelings. I envisioned a Third Wave utopia of friendship and coital intrigue, where I would be no one’s girlfriend, and everyone’s lover, and we’d all watch “The L Word” together and drink. Instead, I was less human than the breakfast pizza. “Haven’t you heard?” I wanted to scream. “We have had a feminist revolution!”

But apparently, we hadn’t. In sexual as in economic capitalism, the free market is rigged. And I don’t mean this in a biologically deterministic or moralistic sense, but in a social one. We’re all surrounded and formed by ideological and material systems—gender, race, class, street cred. If we’re of color, if we’re women, if we’re low-income, if we’re queer or trans or gender non-binary, a lot of times, like a weird sexist version of that Shakira song, underneath our clothes is an endless, socially-dictated story: Slut. Prude. Jezebel. Needy. Whore. Queer. Sex is already vulnerable, because it is already embedded in social systems that say that some people are less human than others. In the game of who-can-feel-less, marginalized people get hurt.

I’m not saying we have to be friends with everyone we sleep with. We don’t have to want to date them. We don’t even have to introduce them to our relatives at parties. (“Look, Grandma, who I met at the Owl!") We do, however, have to acknowledge that our sexual partners are individuals with subjectivities, and insecurities, and vulnerabilities, and feelings that need to be taken seriously, and legitimate fucking needs. Nobody is just a means to an orgasm.

Vulnerability is inherent to all social interactions. It challenges us to think ethically about the ways we engage with other human beings. I think that’s powerful. I think that critical sexual ethics can help us create kinder communities for everybody, not just those who engage in a hookup scene. Eyes bright, faces messy, rising musky from the bed: Isn’t this strange interlude of clumsy pleasure, of wanting bodies, just one more terrain of collaboration, just one of the many luminous, silly workshops in which we make a better world?

Reina A.E. Gattuso ’15, an FM editor, is a joint literature and studies of women, gender, and sexuality concentrator in Adams House. Her column appears on alternate Fridays.

Read more in Opinion

Not Just the R- Word, the F-word, TooRecommended Articles

-

Camp Out, Save WorldThree Harvard students huddle outside a tent in the middle of a deserted Harvard Yard facing the statue of John Harvard at midnight last semester.

-

POSTCARD: What We WantBaseball is a game of regret. No one knows this more than the European baseball player.

-

In Search of Lost Time

In Search of Lost Time -

Harvard Today: October 23, 2014

Harvard Today: October 23, 2014 -

What Title IX DoesWe write as alumnae who have witnessed the law school’s failure to serve survivors, and who believe that our professors’ willingness to outrightly reject an improved-but-imperfect policy perpetuates that unacceptable legacy.

-

Around The Ivies: Plot Twists Ahead

Around The Ivies: Plot Twists Ahead