K is woken hours later by a cursing F, crashing into the bureau on his way to the bathroom. He raises a finger to his lips and mouths the word quiet. He urinates loudly and — she is listening — does not wash his hands. He stumbles out of the bathroom — his belt is unbuckled and his trousers are around his ankles — and toward her.

You’re here, F says. K turns on her side and does not respond. I’ve never been happier to see you, he says. She sees his hand slowly stroke her cheek in the bureau mirror. He kneels to the floor and waits by her side. I knew you wouldn’t do it, he says. She sees him lean closer to place his lips on her cheek. We’re fine, babe, we always have been. He runs his hands through her hair. Trust me. She turns to face him and says, How can I? He does not respond. She asks again. How can I? He does not respond.

K sees F kiss her cheek, her nose, her forehead, her lips, pushing the question back into her mouth. He turns her back on her side. She catches the reflection of his tongue in motion. She feels another wet kiss on her skin. He spreads her wings apart. She pushes him away. Breathing heavily, he bends down to whisper in her ear, But I love you, and continues.

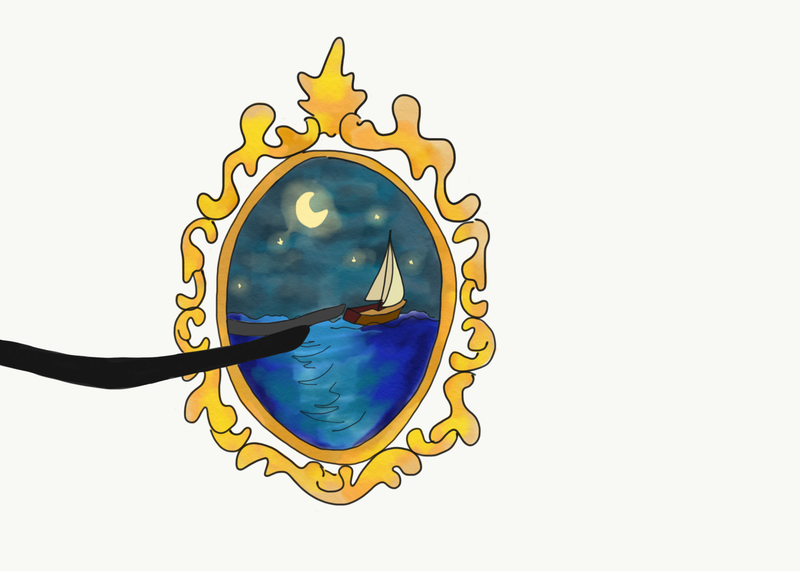

K searches the mirror for strength, but the weight of the world and all its discontents pin her down. F is too heavy to peel off. She is still. Behind him, she can see the reflected moon, the wide and languorous shores of darkness surrounding it, broken only by pinpricks of diffused light. What she sees — solitary glimmerings in the distance — are stars still in the past. In the millions of miles between them and her, time has aged, transformed from past to present. She learned this in high school. She is looking into the night of before. What might the stars see tonight, sitting there at the back of time?

The stars could still be looking down upon the world decades ago, on a night when K sat at home, only a child with her head in her mother’s lap. On a night when the room fills with the sound of a small television, a movie that her mother likes. The images are grainy, the colors are bright and gaudy, and spread outward in a cone of light. The television remote is encased in tattered plastic. All the room’s lights have been dimmed and outside, thunderous rain falls in fast, oblique sheets. Her head is heavy with drowsiness and she drifts in and out of sleep. She feels the rise and fall of her mother’s breath, rolling gently forward like waves.

K’s eyes suddenly flutter open sometime later. Her mother has covered her in a thin blanket — dark purple with a silky magenta border. She turns her head to look at her and, is it the glow of the television? the grace with which her face is at ease with itself?, feels love. You are so beautiful! she thinks. I want to be you. I want to keep you from the rest of the world. She does not say anything. Her mother, as if to tell her that she knows, strokes her hair and puts a playful palm across K’s eyes.

F finishes within minutes; he falls to the side and, though his grunts hang fixedly in the sky above the fishing village for days, is snoring within seconds. K does not sleep that night.

The next day, the couple spends the afternoon at the beach. F plays volleyball with teenagers from a nearby college. K sits on a towel and stares out at the sea: Its glimmerings reveal nothing of the deep world below, only dance mindlessly beneath the sunlight. Waves run after their white-frothed crests and crash against the sand; they turn in circles like chariot wheels. Along the beach, children build sandcastles and chase and flee the tide, and families picnic on the sand, away from the salty spray of the sea. The whole world performs their roles for her to see. She watches them, but from a distance, as if from behind a mirror.

On the horizon, K sees a ship, a beehive, sailing away from the mainland. It is golden beneath the sun, with a mast and sails sewn from threads of sweet honey, lighter than air. Even from a distance, she can tell that the bees aboard do not waste time with words; each breath, each sidelong glance at another sailor is a look of pure meaning. Some are reeling in the anchor to gain speed, some are sweeping the deck and rigging the sails. And though the sun shines brightly down, there is not a shadow in sight. Nothing obscures the light. The bees beat with one heart and are set in motion to the song of their own fluttering wings, which hugs the sails and pushes the ship forward, forward.

K remembers reading a book by Zora Neale Hurston in high school, which opens, “Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board.” She can feel the absence of wishing, of wanting — of thinking wants possible — in her soul. She wonders, nervously, when exactly they boarded a ship and left for brighter ports. She wonders if she can catch the tail end of a passing wind and reach the ship before it is on the open and endless sea. She wonders if she is out there, somewhere, waiting to be found again.

K hawks back some saliva with great performance and spits it as far as she can. She loses sight of where it goes. Maybe it carries part of her off, floating along currents of air to that honeycombed ship in the distance; maybe it lands on the volleyball that F spikes across the net.

—Yash Kumbhat’s ‘21 column of serialized fiction is called ‘Little Deaths’ and is a triptych of short stories that explore the literal and figurative interpretations of a ‘petite mort.’