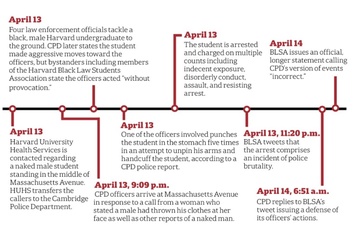

On April 13, a black Harvard College student was violently arrested at around 9:09 p.m. Three officers from the Cambridge Police Department and one Transit Police officer were involved, and the student was tackled to the ground, where at least one officer punched him in the stomach five times in an effort to unpin his arms, according to the CPD report. The student was reportedly under the influence of narcotics. Many have called the incident an example of police brutality.

This story has rattled Harvard’s campus for several weeks, but our reporting began even before that. Originally, we had hoped to shed light on a typically opaque institution—the Cambridge Police Department—and explore the changing nature of police work. Against a backdrop of increased police scrutiny across the United States, the CPD, with its emphasis on community relations, seemed to be ahead of the national curve.

On a chilly March afternoon, weeks before the incident, FM met Cambridge Police Department Superintendent Christine A. Elow in her office. The space is just like any other career professional’s: kids’ drawings pasted on the walls, plaques and awards arranged tidily along the shelves. She’s the second highest ranking officer in the department and the first woman to ever hold her position. And she’s a local. She grew up in Cambridge, attended Cambridge public schools, and, after serving four years with the U.S. Navy, ended up back in her hometown with the CPD.

We departed the station and headed down to the basement, opting for Elow’s Ford over one of the dozen or so squad cars lined up in front of the building.

“Policing is changing,” she said, “and we’ve got to change with it.”

“We have a community that is not shy; they will complain and speak their voice, and that holds across the socioeconomic spectrum,” Elow added. “It’s a very smart city and challenging, and I think as police we’ve really had to take a step back and figure out how we overcome resistance and engage with the community more effectively.”

The department’s goal, Elow said, is to work “cooperatively” with the local population—from students to Cambridge residents, to the homeless community. “We call it social policing here,” she says from behind the wheel of the car. “We are doing more social work than we are police work.”

But the April 13th incident seems to call into question the legitimacy of the CPD’s social policing model, and with it, the original aims of our story.

“The conduct of the CPD on the evening of April 13, 2018 was unacceptable,” a statement by the Harvard Black Law Students Association reads. “We are reminded, as soon-to-be-graduates of an elite law school that we cannot protect our bodies with our degrees—and that is why we also call our current students and alumni to embrace these demands as inclusive to all Black people, not just Harvardians.”

{shortcode-e15b095550465732e99f3ef8484c1221ec9d9159}

A new student group, Black Students Organizing for Change, also formed in the aftermath of the incident. In a letter circulated via email lists to the student body, the organization demanded an extensive report of what happened that evening, and called on the University to create an “internal crisis response team servicing students, faculty, and staff that does not involve law enforcement.”

“As calls for help from Black and Brown folks are frequently met with police violence, students increasingly mistrust law enforcement,” the letter reads.

“We recognize that not everyone will agree with how some incidents are policed,” Elow wrote in an emailed statement after the incident. “It is upon us to further develop procedurally just policing, which is essential to the development of good will between police and communities and is closely linked to improving community perceptions of police legitimacy.”

CPD Police Commissioner Branville G. Bard Jr., the head of the department, echoed these sentiments last week at a press conference. He said the department is conducting a “complete and thorough” internal review, and that he supports the officers who carried out the arrest.

“You have to judge their actions within the context of a rapidly evolving situation and not within an ideal construct,” Branville said at the conference.

***

“I find the incident profoundly disturbing and unsettling,” Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote in an email about the April 13th arrest. Almost ten years ago, Gates had his own run-in and arrest with the Cambridge Police Department.

On July 16, 2009, Gates, a renowned scholar of African-American studies, was arrested on the front porch of his Cambridge home. According to the police report filed at the time, Lucia Whalen, a white woman, had called regarding a possible break-in at Gates’ residence. Sgt. James Crowley responded to the call, and Gates was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct. The charges were later dropped.

“That I was arrested, breaking into my own home—it was a total shock. It took me a long time to get over that,” he recalls from his Hutchins Center office, half a mile from the site of the incident. It’s a large space with an excellent view of Harvard Square, and the walls are plastered with awards and photos.

He pauses and points out a picture, one of many along a shelf. “This is the first time I met Mandela,” he says. Other well-known faces fill his photographs—Bill and Hillary Clinton, Oprah, Toni Morrison, and George W. Bush.

“I just presumed people knew who I was, and so it just never occurred to me that I would have trouble with the police,” Gates says. “As a well-known person in Cambridge connected to Harvard, once they figured out who I was, I was going to be treated like who I was.”

Elow can recall the exact moment she heard of his arrest, down to the minute: “July 16th, 2009 at 10:45 a.m.”

“I remember reporters came in and looked in our records to say ‘Cambridge police is a racist police department’ and for me, growing up here, I took that personally. I’m an African-American woman. We are not a racist police department, but what do we have to shift and change?” Elow remembers asking herself.

His own arrest, Gates reflects, was an “aberration.” Not long after he was booked in jail, a team of Harvard’s most prominent figures and powerful legal experts arrived outside to “raise hell,” he says—from Harvard Law professor Charles Ogletree to current head of the African-American Studies department Lawrence Bobo.

“Within two weeks the officer and I were sitting in the Rose Garden having a beer with Barack Obama and Joe Biden,” Gates says, adding that it would be unfair to generalize from his “atypical” experience. “I realized when I was arrested that if you’re poor and black and you get arbitrarily arrested, you’re in big trouble.”

From Elow’s perspective, Henry Louis Gates’ arrest was a watershed moment for the CPD. “That was the beginning of our dramatic shift, a slow, dramatic shift on how we deliver services to the community,” she explained.

***

Out on the ride along, Elow and patrol officer Hector Vicente continued their discussion of “social policing.” Walking down Central Square, we passed a number of homeless individuals, each one Vicente knows by name. He commented on what they’ve been up to recently and mentioned to Elow if they’ve gotten into any trouble, keeping tabs on all of them.

This type of interaction happened several times. People on the street—a social worker, a homeless woman, a Cambridge resident—seemed to recognize their neighborhood officers, sometimes stopping to make small talk or say hello.

But Cambridge City Councilman Craig A. Kelley suggests that police departments alone cannot act as the community’s “glue.” “There’s something about a badge, a uniform, and a gun that makes most people keep their distance,” he says.

On the council, Kelley has made it his goal to strengthen neighborhood resiliency and build social cohesion in Cambridge, arguing that it is interpersonal relationships—not governments—that best help people through challenging times. When asked about the April 13th arrest, Kelley says the incident highlights the challenge of having police lead the charge on promoting social cohesion.

He says if it were up to him, he would build more public libraries. “There are places for the fire department, there are places for the police department, there are places for public works, but I would target with the libraries or the Department of Public Health. It’s a different approach when it’s not law enforcement or public safety.”

Yet even Kelley admits the unique position police occupy by being able to respond to emergencies in real time. “When you call 911, you’re connected to emergency services, and they can send an ambulance, they can send a firetruck, they can send a police officer,” he says. “What they can’t do is say, ‘Oh, we’ve got a librarian on staff, or we’ve got a social worker on staff.”

***

Though different arrests under different circumstances, Elow wrote in an email that the April 13th incident will receive a response similar to that of Gates’s arrest in 2009. “Per our policy, we have always reviewed arrests and use of force to ensure they comply with department policy,” Elow’s emailed statement reads. “Since Professor Gates’ arrest, one component we incorporated is an evaluation around how could there have been a better outcome on situations that involve discretionary arrest or uses of force.”

Some changes are already in the works. The department currently offers additional non-mandatory crisis intervention training to officers—training which the officers involved in the April 13th arrest had yet to participate in—designed to instruct them on how to manage situations with mentally ill individuals. Additionally, according to a proposed Cambridge budget for fiscal year 2019, CPD will add a new office to monitor use of force and racial bias in officers’ interactions.

Addressing changes in policing since Gates’s arrest in 2009, Elow also notes the increasingly influential role video and social media have come to play. “Both mediums can potentially create support or divide in any situation. Since the April 13th arrest took place, we’ve been extremely proactive, particularly online and in-person, with the community discussing this incident, our training, and our beliefs and values,” she wrote.

She goes on to mention how leaders from the CPD had participated in forums, neighborhood meetings, and a Public Safety Summit at Harvard over the past week. “These types of opportunities are so important in building trust through transparency and, due to our collaborative relationships and use of technology, we have never had more platforms to engage with the community than we do today,” Elow writes.

The CPD’s pivot towards Elow’s “social policing” model remains an important aspect of Cambridge’s efforts to build social cohesion in the community—and it now needs to include an effort to restore its credibility as well “Earning the community’s trust and confidence is of the utmost importance to the Cambridge Police Department, but we also recognize that any one interaction can shape one’s view of the police,” Elow writes. “That trust has to be constantly earned by ensuring the Department adheres to the principles of procedural justice and legitimacy as well as fair and impartial policing.”

–Magazine writer Andrew W.D. Aoyama can be reached at andrew.aoyama@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @AndrewAoyama.

–Magazine writer Isabel M. Kendall can be reached at isabel.kendall@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @IsabelMKendall.