{shortcode-f240610cc220e67ba3535a94763fe26258cf2cf5}

Though former University President Drew G. Faust has yet to come to Harvard’s defense in the ongoing admissions trial, another former Ivy League president took the stand Tuesday to argue in favor of giving preferential treatment to wealthy and well-connected applicants in the admissions process.

Ruth J. Simmons, president of Prairie View A&M University and the former president of Brown University, defended Harvard’s practice of giving “tips” — meaning an extra boost — to legacies, students linked to top donors, children of faculty and staff, and both recruited and non-recruited athletes.

Simmons said alumni of elite universities can have a strong positive impact on their institutions, making it “important” to give an extra nudge to legacy applicants. At Harvard, the legacy admit rate is five times that seen by non-legacies.

“It is entirely appropriate for them to believe that it would be wonderful if their children could also enjoy the same benefits that they enjoyed as students,” Simmons said of alumni of Ivy League institutions. “We’ve been made stronger by benefit of that [alumni] involvement... one way for us to signal how important that is to us is that we consider their children in the context of our admissions process.”

Under cross-examination, Simmons conceded that she believed fewer people would donate to Harvard if the school eliminated its legacy preference.

Simmons insisted, however, that an applicant who is not qualified would “never” be admitted simply because of his or her legacy status, noting it would be “highly unethical to admit students who you don’t believe will thrive.”

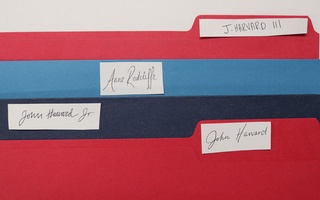

Nonetheless, an email exchange between Harvard administrators presented in court on Oct. 19 seems to suggest less-qualified legacy applicants sometimes do make it to Cambridge. In one of the emails, Harvard's director of admissions Marlyn E. McGrath ’70 described an applicant — whom she identified as a black legacy — as a “terrible case,” admitted “entirely for contingent reasons.”

Harvard lawyer Seth P. Waxman ’73 also questioned Simmons about the tip given to the children of donors. Internal emails filed in court show that Harvard favors those who fund it; in one case, an admit’s relations seemed to promise to fund a new building around the same time the high schooler won a spot at the College.

Simmons defended the practice, saying that donor gifts and support allow private institutions to “not just survive, but become stronger in every era.”

Simmons said that unqualified applicants are “never ever” admitted because of a large donation and that such a practice would be “completely inappropriate.”

While Harvard’s admission of legacies and the children of donors has drawn scrutiny during the trial, directly at stake is its race-conscious admissions policies — anti-affirmative action group Students for Fair Admissions charges that the University discriminates against Asian-American applicants.

Simmons, the first black president of an Ivy League institution, spent much of her testimony asserting the importance of diversity in higher education. At times, she cited her own experiences.

“It’s very hard for me to overstate my conviction about the benefits that flow from all of these areas to a diverse undergraduate student body. I know something about a lack of diversity in one’s education,” Simmons said. “I know what it was like to walk down the streets where random people attacked us or issued slurs.”

Simmons also defended the special consideration Harvard gives other groups of applicants including the children of faculty and staff. She said elite universities are always competing for the best faculty, so giving professors' children a tip is a needed recruiting tool.

Things lightened up slightly in the courtroom during a later discussion about student-athletes. For a moment, school rivalries surfaced in a courtroom in which more than a few lawyers and witnesses boast degrees from Ivy League institutions.

“We are an athletic league. How are we going to field teams to play each other if we don’t admit athletes for those teams?” Simmons said. “A lot of people outside the Ivy League believe we’re not serious when it comes to athletics, but that’s because they’ve never sat at a table of Ivy League presidents fighting about athletics.”

“When Brown beat Harvard, it was a holiday. So these are serious matters,” Simmons continued, prompting laughter from several lawyers and trial attendees.

— Staff writer Cindy H. Zhang can be reached at cindy.zhang@thecrimson.com

Read more in College News

Bacow, Keeping Close Tabs on Admissions Trial, Says He Remains Confident Harvard Will WinRecommended Articles

-

UC Defends Affirmative Action, Calls for Changes to Admissions Process

UC Defends Affirmative Action, Calls for Changes to Admissions Process -

Bob Dole, the Department of Education, and the Nebulous Fight Against Legacy Admissions

Bob Dole, the Department of Education, and the Nebulous Fight Against Legacy Admissions -

Wealthy Applicants Should Not Get a Leg Up in Admissions

Wealthy Applicants Should Not Get a Leg Up in Admissions -

‘Arrogance.’ ‘Small-Town Insecurity.’ Here's Why Harvard Hesitates to Accept Some Applicants

‘Arrogance.’ ‘Small-Town Insecurity.’ Here's Why Harvard Hesitates to Accept Some Applicants -

Here’s How the Harvard Admissions Process Really Works

Here’s How the Harvard Admissions Process Really Works