This past semester, Economics and Computer Science again ranked as the most popular concentrations at Harvard College. No surprise here. After all, these two concentrations are often seen as having the most direct applicability to lucrative jobs on Wall Street or Silicon Valley. Who could blame students for wanting to get a quick return on the four-year investment that is an undergraduate education at Harvard?

Considering this, it makes sense for students to pigeonhole themselves and take classes that will prove handy after graduation. I‘m sure you’ve heard as much as I have from classmates looking to “take an easy class and knock out a Gen Ed requirement,” so they can begin taking “what’s actually useful.”

When I hear such remarks, I’m reminded of the students I spoke to halfway around the world—in China—where I recently toured with Glee Club Lite to visit a dozen universities and high schools. Students there speak of an education system that emphasizes strict rigidity, learning for the sake of taking tests, and specializing very early in their lives.

Chinese students are placed into universities by the scores they receive on the Gaokao, the country’s infamously challenging college admissions exam. It is a grueling ordeal where a single point could mean the difference between admission and rejection from universities. Students select a major before the exam’s results even come out, and they are admitted based on the scores they receive in relevant fields on the exam.

For example, an incoming college freshman may commit to majoring in mechanical engineering at a certain university without actually having ever taken a course in that field, or even a single course at that university. Students are compelled to typecast themselves into a major because they were admitted to specialize in that field—a sensible expectation, as all of China’s best universities are under the purview of the country’s government and are designed to allocate professionals to each industry of the Chinese economy.

As a result, Chinese students will never enjoy the opportunity to “shop” classes in whatever field they choose, or to enroll in courses that simply interest them. Most will never be able to take an actual college class before declaring their major, let alone be exposed to a liberal arts education. They will, however, take courses and study subjects that are immediately and directly applicable to the jobs they take upon graduating. As a result, they will have very little room to discover their true passions.

Their education is, at the end of the day, a means to an end. In elementary, middle, and high school, students prepare to take the all-important Gaokao. And in college, they study to prepare themselves to obtain a job after graduation. Education, by and large, is not a way to train students in deep and critical thinking, but rather a shortcut to a lucrative job after graduation.

Their system could not be more different than the one we have at Harvard. We are encouraged to discover our genuine interests before declaring our concentration, and we are challenged to take classes that are completely unrelated to our field of study.

We, as Harvard students, should not waste this valuable opportunity to find what we actually love to do, for that is a privilege many college students elsewhere will never enjoy. Our time here marks a chance for us to discover our comparative advantage, if you will—the field or area where we can make the greatest impact. We have the freedom and the power to shape our lives around what we do best and what we truly enjoy.

So next time, when you choose classes, go for a class in philosophy, or history, or chemistry. It may very well spark something that changes your intellectual trajectory. And while such classes may not help us to find the most immediately lucrative job out of college, they will certainly pay dividends in the long run. They will offer us new perspectives on the world and make us more inquisitive and more powerful thinkers.

Andrew W. Liang ’21, a Crimson editorial editor, lives in Wigglesworth Hall.

Read more in Opinion

Sticks and StonesRecommended Articles

-

Fairbank Discusses Crisis of Chinese Universities as Book Drive StartsOpportunity for Harvard to make clear its position in the Sino-Japanese War and take a real step in furthering international

-

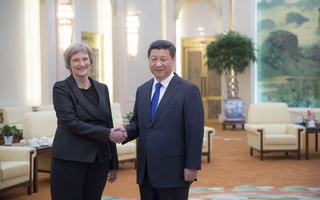

Faust Discusses Climate Change at Beijing's Tsinghua University

Faust Discusses Climate Change at Beijing's Tsinghua University -

Making Diversity MeaningfulBut as Harvard (to its great credit) becomes more inclusive and diverse, more students need a leg up when they arrive. By the same token, the better-off, better prepared students would do well to spend more time directly engaging with students who are truly different from them.

-

Hindering Higher EducationWe are extremely disappointed with this provision of the House’s tax plan. It disproportionately harms graduate students across the country who contribute knowledge, teaching, and labor to our educational institutions.

-

The Whiz Kids

The Whiz Kids