Eyeing the security guard on the second-floor balcony and the Secret Service agents a couple yards away, Harvard graduate student Avriel Epps reached under her shirt and pulled a large banner reading “WHITE SUPREMACIST” from the waistband of her jeans.

In front of Epps, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos—wearing a cornflower-blue dress and gripping a lectern in the center of the Institute of Politics’ John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum—had just launched into a speech arguing for “school choice.” Behind Epps, more than a dozen journalists crammed into a press pen clattered away on laptops or clutched cameras.

Epps fought down terror, forced her brain to “empt[y] out.” Then she stood up. She faced the press and unfurled the banner.

“I was calculated about it, I wanted to make sure I was in an area where the photographers who were behind me in the press pit could get a shot of [DeVos’s] face with that sign,” Epps remembers.

Epps was one of roughly two dozen protesters, all smuggling concealed banners, who infiltrated the forum Thursday, Sept. 28, the night DeVos visited Harvard’s campus. Epps was the first to rise from her seat—but her lone stand kicked off a timed sequence of demonstrations, the culmination of a week of meticulous plotting.

{shortcode-f22522f3faac558e668d7369d3f217f837caaf7c}

Organizers assembled their protest limb by limb: They recruited students, scored almost two dozen tickets to the restricted speech, researched past protests, consulted Graduate School of Education administrators, held group-wide votes to determine the best plan of action, and stayed up until 2:30 a.m. the night before the event finalizing tiny details.

On Sept. 28, the planning paid off: Harvard students seeded around the room hoisted banners at regular intervals in total silence, stunning Kennedy School officials and drawing immediate national media attention. Demonstrators spoke up only as DeVos left the forum, pointing at the secretary and calling out, “That’s what white supremacy looks like!” The protest remained peaceful throughout: Not one student was escorted from the room by police.

Kennedy School Dean of Academic Affairs Archon Fung, who moderated Thursday’s discussion, says he has attended maybe three dozen forum discussions since he took a job at the University in 2000. But in nearly two decades at Harvard, Fung says he has never seen a protest “anything like that” before.

If the protest is unusual in Harvard history, it also breaks from a recent media narrative of protests at American universities: Students, sometimes violently, seek to prevent controversial right-wing speakers from setting foot on campus. In February, the University of California at Berkeley cancelled a scheduled speech by far-right provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos after protesters threw Molotov cocktails and caused $100,000 in damage; in March, demonstrators at Middlebury College prevented controversial theorist Charles A. Murray ’65 from speaking and injured a professor in the process.

DeVos, a President Donald Trump appointee, checks both boxes: conservative and controversial. She has long drawn fire for her advocacy for the school choice movement, which seeks to offer alternatives to traditional public schools. More recently, she earned widespread criticism for her decision to rescind Obama-era Title IX guidance that required schools to use a lower standard of proof when judging whether an accused student is guilty of sexual assault.

“People have been shutting down conservative speakers across the country and one side effect of that is that it’s enabled the conservative right [to] claim their free speech is being suppressed,” says Kennedy School student Jeff Rousset, who helped organize the protest against DeVos.

Demonstrators hoped to decry DeVos’s policies and highlight what they saw as Harvard’s complicity in legitimizing them—but they also wanted to “reclaim the narrative” of peaceful protest in the United States, according to organizer and Education School student Natasha Daniella Rivera. She and Rousset attribute the success of the event to preparation, careful planning, and to demonstrators’ status as Harvard students—which, the two say, offered a national stage and ensured protection by University police.

By design, all protesters donned Harvard sweatshirts, T-shirts, or wore the color red that Thursday. “We used the privilege of the H,” Rivera says.

It started with a text.

Sophia Perlaza, a student in the Graduate School of Education, was scrolling through Facebook when she saw it: Hundreds had signed up to attend a protest against Education Secretary Betsy DeVos the next week on Sept. 28.

Perlaza screenshotted the event, titled “Stand for All Students: #StopDeVos,” and sent the picture to a new friend she’d met a few weeks ago, fellow Education School student Rivera.

“Protest or nah?” Perlaza texted.

Rivera was enthusiastic. She reached out to a third friend, Education School student Andrew Greenia, who replied: “Let’s do this.” None of the three had any experience organizing protests or belong to activist groups on campus—but in just a few days, relying on relationships forged swiftly through Facebook and email, the trio connected with dozens of other students around the University to forge one of the most unusual demonstrations in recent Kennedy School history.

Sprawled on a picnic blanket in Cambridge Commons the Sunday afternoon after the protest, five of the event’s main organizers—Rivera, Perlaza, Greenia, Rousset, and College student Amelia Y. Goldberg ’19—recall the week leading up to DeVos’s speech, occasionally pausing to snack on oranges and granola.

Rivera, Perlaza, and Greenia agreed to meet at 8 a.m. in the Monroe C. Gutman library Thursday Sept. 21, one week before DeVos was slated to visit campus. That morning, the three immediately began emailing and messaging people they “thought would be potentially interested” in helping, Rivera recalls. The trio also created a private Facebook event and invited friends—and then friends of friends.

A former summer student of Rivera’s connected her via email with Goldberg, who organizes for anti-sexual assault advocacy group Our Harvard Can Do Better. Goldberg put Rivera in touch with members of the Harvard Graduate Students Union and the Harassment/Assault Law-Student Team; both groups had already been meeting separately.

A few days later Rousset, who had already been trying to organize students to protest Harvard’s decision to rescind Chelsea Manning’s IOP Visiting Fellowship, joined, too.

“It was this sort of natural way our energies found each other,” Rivera says. “Literally through email, email and texting.”

The numbers slowly grew. Roughly 15 people attended the informal group’s second meeting, held Sunday Sept. 23 at 4 o’clock in Cambridge Commons. More than 20 came to the third meeting, a “poster-making” session held Tuesday Sept. 26 in a Harvard Law School lounge.

The planners decided early on to focus on disrupting DeVos’s speech from the inside—they felt the extant protest outside the IOP, organized by larger local groups including the Massachusetts Education Justice Alliance, had enough steam on its own. (By Sept. 26, more than 1,000 Facebook users had indicated they were interested in attending.)

Seats inside the DeVos event, though, were available almost exclusively to Harvard students, who had to lottery to earn a spot. The protesters and their friends lotteried for as many seats as they could, ending up with 23.

The plan for Thursday slowly took shape across the in-person meetings and in online discussions—students voted on some decisions, but “largely operated by consensus,” Goldberg says. Meanwhile, Rivera and others did background research, talking to Education School administrators and alumni about past protests: what worked, what didn’t, what to expect.

Students spent their fourth and final meeting—held the day before DeVos’s speech in an off-campus apartment—finalizing details and banners, scrawling slogans in red paint on white bedsheets and pillowcases. Some stayed until 2:30 a.m., fueled by Twizzlers and Veggie Straws.

By the next morning, everything was ready. In total, protesters had spent less than 30 dollars preparing: buying poster materials, paint, and snacks.

Epps did not want to hold the “WHITE SUPREMACIST” sign. She wanted to raise a different banner, a larger one reading in part, “HARVARD LEGITIMIZES WHITE SUPREMACY.”

But Epps is tall—five foot ten (she once worked as a runway model). Rivera asked if Epps would stand up first, with the smaller sign, on the ground floor of the Kennedy School’s JFK Jr. Forum, close to the press.

“We were starting to think about what kinds of folks would be easily visible and cause the most disruption by standing,” Epps says. “So Natasha asked me to do it because I’m tall and have big hair.”

She laughs. “I think that is essentially what it came down to.”

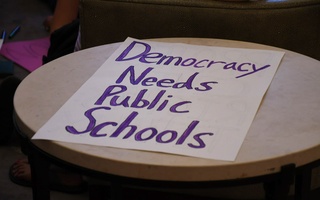

A couple minutes after Epps stood up, another protester hoisted a different sign, “RECLAIMING MY DEMOCRACY.” Then, a couple minutes later, another: “OUR STUDENTS ARE NOT 4 SALE.”

The JFK Jr. Forum is a large split-level space with multiple layers of balconies. Over the next half hour, protesters unfurled ever-larger banners from ever-higher floors at regular intervals.

Rivera, Perlaza, Greenia, Rousset, and Goldberg call this the “tiered” approach: a way to prevent police from escorting protesters outside the building the minute they raised their posters.

“I didn’t want everything to happen in one go and then it was over in five minutes,” Rivera says. “I wanted a sustained way of protesting, of having groups stand up and deliver their messaging… The tiered approach [also] had the greatest visual impact.”

Goldberg adds the method was meant to simulate dialogue between protesters and DeVos. Though never interrupting the secretary verbally, the protesters—by revealing a new banner every five minutes or so—still created “something like an exchange,” Goldberg says.

Goldberg says protesters’ decision to remain silent was twofold. On one hand, it reflected their belief that DeVos’s agenda and policies—particularly her recent decision to cancel the Obama-era Title IX guidance—will prevent students who suffered sexual assault from speaking out.

On the other hand, demonstrators wanted to applaud DeVos for choosing to take questions, many of them antagonistic, from a crowd that sometimes sided with the anti-DeVos demonstrators.

“We wanted to acknowledge that the JFK Forum was in some ways dedicated to be a place for free speech,” Goldberg says. “And that providing students an opportunity to ask unwelcome, uncensored questions is not something that education careerists and particularly Secretary DeVos often agrees to.”

Rousset says he thinks the visual protest sent a loud message nonetheless.

“I think it was a beautiful symphony orchestra where everybody was playing a role, playing an instrument,” he says. “It built up to this crescendo. There was a rhythm to it.”

Afterwards, jubilant, the students headed en masse to popular Harvard Square restaurant Felipe’s to feast on margaritas and burritos. Rivera, Perlaza, Greenia, Rousset, and Goldberg recall an outpouring of congratulations from friends and family. Goldberg particularly remembers receiving an email from her nonagenarian great aunt.

On Sunday, three days removed from those celebrations, the five organizers seem relaxed and unfocused, chatting and laughing. But asked what they’re planning next, everyone sits up a little straighter.

“We’ll see,” Rivera says.

“[Harvard] will be hearing from us,” Goldberg says.