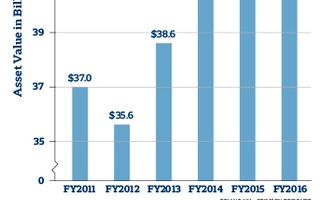

If money makes the world go round, then huge gobs of it power the juggernaut that is Harvard. The sheer dollar values are staggering. The endowment reaches towards $40 billion, a sum larger than the economies of 103 countries. A record-breaking $6.5 billion capital campaign is under way, itself larger than the economies of 45 sovereign nations. Indeed, hardly an eye is bat when the construction proposals floated by administrators top $1 billion. (The Allston science complex has a dollar value greater than 15 entities represented at the United Nations.)

Over the past year, the University’s finances have weaved their way into many of the most important news threads. From the capital campaign to campus activism to the national debate over the cost of education, the proper role of the endowment has been a key issue. Major donations like that of John Paulson’s last summer provoked scrutiny over the size and worthiness of the endowment. Law School protestors have demanded tuition be eliminated. Numerous editorials and op-eds on these pages have encouraged Harvard to spend its nest egg differently. Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’s proposal for free college has sparked a national debate about the spiraling cost of higher education.

As the year concludes, we have revisited the numbers behind the policy choices that are often discussed on campus. Indeed, Harvard’s dozens of financial statements over the past decade reveal the pragmatic choices and practical realities facing administrators confronted with both internal and external demands. Unfortunately, the endowment is poorly understood, giving rise to demands that are often unrealistic.

The Post-Crisis Endowment

Over the course of one year — 2008 — Harvard’s endowment lost $11 billion. As the economy headed for the deepest recession since the 1930s, administrators responded by postponing Allston expansion plans and instituting budget cuts, including nearly $200 million in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

In particular, the high proportion of Harvard’s endowment tied up in illiquid assets, or those that cannot easily be sold, meant that administrators faced a particularly severe cash crunch. No doubt these memories continue to loom large in the minds of administrators.

Today, Harvard Management Company, the University’s in-house investment arm, faces a different problem: underperformance. Since the recession, their performance has lagged both their past results and peer institutions. In fiscal year 2015, only one Ivy League institution, Brown, fared worse than Harvard. Peers at Yale and Princeton delivered 11.5 percent and 12.7 percent, respectively, to Harvard’s 5.8 percent. Whether this is a result of poor investment decisions or a conscious choice to become more risk-averse is unclear, but even President Faust has acknowledged that poor investment returns are deeply concerning.

{shortcode-c670d9cfa2115de0b784380903137c3ba1930aef}

HMC CEO Jane Mendillo was replaced in 2014 with Stephen Blyth, who has promised to shake up the fund. As we have said in the past, in the long run, HMC returns and not fundraising will shape the size of the endowment. After all, a 1 percent change in performance with a principal as large as Harvard’s has a $370 million impact, a sum larger than the then-largest-ever gift to Harvard that renamed the School of Public Health. Had Harvard matched Stanford’s performance last fiscal year, the endowment would be hundreds of millions greater than it is; had Harvard matched MIT, the endowment would be billions larger.

The Endowment’s Reach

Far from being an idle contest between Ivy League universities to top each other, the size of the endowment has real and tangible impacts on Harvard’s campus. The global financial crisis illustrated this clearly. Expansion plans were postponed, hiring was downsized, and budgets were slashed. Since then, the share of the budget coming from endowment returns has remained relatively constant near 35 percent.

{shortcode-b5964093d5f4efea6417f1f774eac59039e6e2ae}

As costs inevitably increase, the University will be forced to find new ways to grow revenues. Financial aid has long been sacrosanct (it was one of the few budgetary items untouched in 2008’s budget cuts), so tuition rises only have a limited impact on the bottom line. As a result, as the Harvard Financial Aid Initiative was rolled out and expanded from 2004 to 2008, tuition growth lagged endowment returns by 26 percent. From 2008 to the 2015, the most recent year for which data has been released, they have grown roughly in parallel.

{shortcode-d8d3de01b22bd0f2ab56f809f59bc95ad4f872be}

That financial aid is expensive does not mean it is wrong. Indeed, as Harvard students, we’re proud of the commitment that this institution has made to opening its doors. Any continued steps towards that goal are welcome. The socioeconomic diversity that is enabled by these programs firmly make Harvard a better place.

Nevertheless, we believe that the data demonstrates that those who can pay, should. Contrary to claims made by Board of Overseers candidate slate Free Harvard, Fair Harvard and suggested by Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, endowment money would be woefully insufficient to cover the cost of educating Harvard students. Last year, 23 percent of the FAS budget, of which the College is a part, came from tuition. At the Law School, the site of the anti-tuition activist group Fees Must Fall, a huge 46 percent of revenue came from students. The endowment is certainly to be celebrated for making possible these relatively low numbers—it pays for 50 percent and 33 percent of the FAS and Law School budgets, respectively—but it is clear that absent an unexpected doubling of the endowment, tuition must continue to pay for significant portions of the Harvard budget.

{shortcode-dc710b65856e5e2f33ce2ceeabe73d52d9751791}

Alternative Revenue

To continue to make possible growth in financial aid as well as other important priorities like research, faculty hiring, and House renewal, we encourage the administration to expand the growth of non-tuition revenue. Improving HMC’s performance must be the foremost priority, but alternative sources of funding are critically important. This challenge has been made more difficult by the dropoff in federal funding due to budget cuts, amounting to a $100 million cut from its 2011 peak.

{shortcode-03f92809e8b5954950379907e72363b232a96b76}

In its place, foundations and corporations have grown in significance. From 2009 to 2013, the last year a breakdown of data was publically available, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation more than doubled its giving to Harvard research. In some cases, the sums are significant: in 2013, 21 percent of the School of Engineering and Applied Science’s non-federal sponsored spending came from the German chemical company BASF; 24 percent of the School of Public Health’s and 35 percent of the Graduate School of Education’s came from the Gates Foundation; and 8 percent of the Kennedy School’s non-federal expenditure came from the China Southern Power Grid Company. The donors are also heavily concentrated: four of the ten largest non-federal sponsors are pharmaceutical companies.

It is no coincidence that the Medical School, which of all degree-granting Harvard schools has the highest percentage of the budget coming from research sponsorships (39 percent), also has the lowest percentage of the budget coming from tuition (7 percent). Though some groups like Divest Harvard have raised conflict of interest questions about corporately-funded research (in 2013, Harvard’s largest foreign sponsor was a Spanish energy giant), universities must be proactive about finding new sources of revenue.

Throughout the University, executive education programs enable growth of other less lucrative programs. In 2013, these continuing education programs surpassed undergraduate tuition, reflecting a University willing to explore alternate streams of income.

{shortcode-45e2641229f4735cd4175fbbe3d589a721108977}

The Future of University Finances

Ultimately, these numbers paint a picture of a university bound by the realm of the possible. Budgets must be balanced and costs must be covered. Of course, this might be frustrating to some. It certainly slows the pace of change, but only through this sort of pragmatic attention to budgets and implementation details does change happen. Instead of radical changes like free tuition, Harvard has steadily grown the size of its financial aid program by growing alternative sources of revenue.

Indeed, it is simply not possible for the endowment to fund a substantially greater portion of the University’s affairs than it currently does. The endowment is not a $37.6 billion trust fund or magical pot of money — it must be carefully managed so that it is not quickly depleted. Only a certain portion of endowment funds can be made available each year. Indeed, absent alternative sources of income, the University risks repeating the reliance on endowment returns that can vary with the market. Better understanding the nature of the University’s finances is critical, and it is often disappointing that criticism of Harvard misunderstands the nature of the endowment. These issues deserve a debate that is informed, intelligent, and applicable.