It’s expensive to die in America. The trappings of a standard burial add up quickly. Some costs are familiar: the casket or cremation, the service, the hearse. Others aren’t: the embalming fee, the cosmetics, the thick vault of concrete which lines every grave.

These costs typically fall to the living, but they’re also hard on the land. In 2014, The Atlantic reported that the funeral industry buries over 1.5 million pounds of concrete vaults and metal coffins each year—containers which will far outlast their contents. Embalming and cremation aren’t great either. Formaldehyde, a common ingredient in embalming fluid, has been linked to increased cancer risk, cremation to high outputs of carbon dioxide.

Esmerelda Kent, a San Francisco designer who bears an uncanny likeness to “The Incredibles” character Edna Mode, sees her company as a solution to these problems. Kent’s business, Kinkaraco™, sells biodegradable burial shrouds in a range of styles. Her wares have been buried across America, Canada and Australia, from the set of “Six Feet Under” to Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, a certified “green burial” site.

Like most people, Kent’s first ties to funerals were personal. When we speak on the phone early Thursday morning, Kent tells me about a grim election night in 2000. Kent’s mother was dying in a convalescent home. Al Gore was losing on a small TV. When the movers took away the body in a black plastic bag, they saddled Kent with a fourdigit bill just for their service. When Kent tried to arrange a simple cremation, she found added fees at every turn. This experience laid the ground for what would become Kent’s business.

In photos on her website and her LinkedIn profile, Kent has a drama teacher’s eccentricity—large earrings, loose fabrics, and swollen coke-bottle glasses. When her hair’s not pulled back in a soft, Katharine Hepburn bun, it’s up in an old Hollywood turban, like Lana Turner in “The Postman Always Rings Twice,” if Turner had been, as Kent puts it, a “goth kid.” Kent self-identifies as Buddhist, although her particular brand of western spirituality might be best illustrated by its inspiration: a reading of Herman Hesse’s Siddartha at age 15.

When her mother died, Kent was working as a costume designer. She fell deeper for funerea, and took a job at Forever Fernwood, a cemetery outside San Francisco, then one of only three green cemeteries in the country. Oriented away from the costly and toxic methods of conventional funerals, green cemeteries bury a lot of shrouds. Kent found that the shrouds used for burial often wanted design.

“People were bringing bodies wrapped up in shawls and quilts and bedsheets,” she says. “It looked horrible. They leaked and it was a mess. Because I had been a designer, I saw what was needed to cover all the bases.”

The garment Kent cooked up had to be strong— thick muslins, thick silks. It needed handles for carrying, and a board to support the body. It needed to be light, and it needed to be beautiful.

“I used to design for ballet dancers and aerialists, where someone would come out on stage and you had to be able to pull the suit off of them really fast. I’ve been designing for bodies, for different things for years. This was just another thing a body was doing,” Kent says.

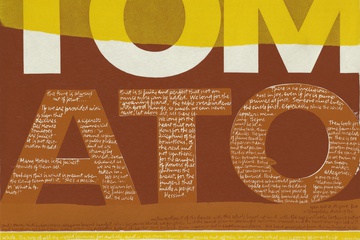

Sixteen years later, Kent’s website, an exercise in earnest 2000’s web design (misformatted pictures and fonts with serious serifs), pushes a wide range of products. Under a banner with their motto, “Look beautiful in the last thing you’ll ever wear!™” Kinkaraco offers seven styles of shroud for every income bracket. For the indulgent, the “MORT COUTURE™” line includes soft french silks or black Victorian cottons (The RAVENWING™ goes for $666.00). The nautically inclined might choose the model for burial at sea, while the more modest could go for the TRU-GREEN BELIEVER™, which sells for $299.00. Two styles will make the culturally conscious squirm: The AFRICAINE™, which seems to condense the entire African continent into one tribal pattern and the VARANASI™—yes, a white woman trademarked India’s most sacred city.

All of Kent’s models cost less than caskets (save for the KINKARACO KART™, $3999.00). The self-described “taphophile” says affordability is part of the shroud’s appeal. Another appeal, she argues, is the shift in narrative.

According to Kent, current funereal conventions are relatively recent phenomena—relics of a post-World War concern for preservation, even in death.

“People from that generation had come out of the Depression and then World War II. They wanted everything to look perfect. They wanted makeup on the bodies and they wanted them to be wearing a nice dress and look like they were asleep. They bought their plots pre-need. They paid rent on them like houses,” Kent explains.

Between the Civil War and World War II, embalming gradually lost its social stigma and transitioned from taboo to the norm. The rise of embalming coincided with early cemetery vaulting and a shift in funeral language from words like “undertaker” to the less explicit “funeral director”—all, Kent argues, signs of a culture turning away from realities of decay.

Kent calls her shrouds “realist”—they do less to shield the body, physically and emotionally. Instead of a casket and a concrete barrier, only a layer of fabric separates body and ground.

Corpses are meant “to be put right in the ground to compost,” Kent says. “That’s the nature of the human body.”