Before spring break, representatives from the 12 houses excitedly raced through Harvard Yard to inform their future housemates of their fates. Over 100 freshmen were soon regaled with chants of “Lowell! Lowell!” Most were pleasantly surprised. But the former Harvard president’s name was not always synonymous with welcoming.

When Abbott Lawrence Lowell assumed the Harvard presidency in 1909, Boston Brahmins and alumni of elite boarding schools made up most of the College’s student body. In an attempt to diversify, the admissions committee of the day created the “Top Seventh Rule,” which required Harvard to reach out to boys who finished in the top seventh of their class, regardless of school or location.

The committee issued a report in April of 1923 suggesting that the rule would benefit applicants from underrepresented areas: “While no geographic restriction is contemplated, it is thought that the new opportunity would appeal particularly to rural schools and to those situated outside the regular Harvard recruiting ground.”

Lowell himself, however, attempted to restore Harvard’s traditional demographics by requiring applicants to demonstrate “character” as well as good academic standing through recommendation letters and interviews. An appointed committee stated that these new requirements would help “eliminate the intellectually unfit” and ensure that “the student body will be properly representative of all groups in our national life.” However, Lowell used these requirements to ensure a lack of diversity.

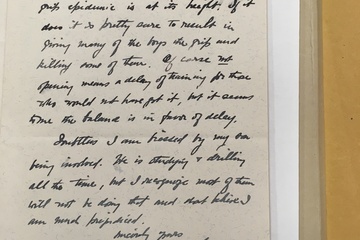

Lowell even attempted to establish a direct quota on Jewish students, who comprised more than 20 percent of the total undergraduate population in 1922. Lowell justified his quota by suggesting that limiting the Jewish population would help eliminate anti-Semitism. “The antiSemitic feeling among students is increasing, and it grows in proportion to the increase in the number of Jews,” Lowell wrote in a 1922 letter to the Class of 1900’s Alfred A. Benesch. “If [the] number [of Jews] should become 40 percent of the student body, the race feeling would become intense. If every college in the country would take a limited proportion of Jews, I suspect we should go a long way toward eliminating race feeling among students.”

The Committee of Thirteen, assigned to rule on Lowell’s proposed 15 percent quota, rejected Lowell’s proposal in the 1923 report on the grounds that “Harvard College [must] maintain its traditional policy of freedom from discrimination on grounds of race or religion.”

Lowell’s prejudices did not stop at Jews. In 1922, Lowell expelled all black students from Harvard Yard. “We have not thought it possible to compel men of different races to reside together,” Lowell wrote in a letter to the Class of 1902’s Roscoe C. Bruce. “We owe to the colored man the same opportunities for education that we do to the white man; but we do not owe it to him to force him and the white into social relations that are not, or may not be, mutually congenial.” Lowell’s reasoning in this case was “the colored man [claiming] that he is entitled to have the white man compelled to live with him is a very unfortunate innovation which...would increase a prejudice that...is most unfortunate and probably growing,” echoing what he used to justify his quota.

Lowell also formed the “Secret Court of 1920” to purge gay students from Harvard. The Secret Court, which went unreported until 2002, expelled eight students and fired two teachers as a result of uncovering homosexual activities on campus.