Dan C. Hazen, Ph.D., has recovered books from the battlefield. While working for a Nicaraguan library in the 1980s, Hazen led a team to salvage political documents from local government buildings overtaken by the Sandinistas. Storming into offices whose occupants had been exiled, the archivists attracted some suspicion.

“They were like, who are you people? Librarians? Yeah, right.” Hazen, now the associate librarian for collections development at Widener, shrugs off the mission with the cool confidence of an adventure-movie hero—“it was an unusual experience.”

Hazen does not look, at first glance, like the Indiana Jones-type. He wears a neat gray sweater and wire-rimmed glasses; his fingers perpetually clasp an uncapped pen. His desk, buried under eight or so neatly stacked piles of paper, stands out in an otherwise spartan office. In an adjacent conference room, he sits two seats away from me, because I have a cold (germy hands fare badly with rare manuscripts).

But Hazen, from his office, can view the world.

“That over there is Latin America, that’s Western Europe, and that’s India,” Hazen says, pointing to a cubicle decorated with an image of the Buddha. Sub-Saharan Africa is downstairs. Hazen oversees Widener’s Collections Development Department, staffed by about 60 or 70 archivists, divided by geographical area of expertise. The librarians spend much of their time outside of those cubicles.

“Our librarian for sub-Saharan Africa is working in a Yoruba-speaking area of Nigeria, developing a database of Yoruba speech and transcribing oral statements,” Hazen says, referencing a current project. Another staff member recently visited Germany to track down a film buff for a collection of reels; a third searched for science fiction comic books in Alabama.

“We got into some funny situations in Russia,” Hazen reminisces, leaning back in his chair. “Stuff that was property of the state back in the day, now somebody says it’s theirs... it’s not always clear whether they really own it.” (Revolutions from Nigeria to Russia upend the book world, too.)

While Hazen’s librarians obtain most mainstream academic materials from established bookdealers and donors, rarer documents turn up in unlikely (and sometimes reluctant) hands. The original charter for Harvard University, stolen decades ago from the Massachusetts archive, ended up in the possession of an individual who refused to sell it to Widener for no less than a million bucks. Hazen passed—price aside, “I didn’t want Massachusetts to come knocking on our door.”

Library acquisition, Hazen explains, yields a greater reward than stolen treasures. “You’re building representations of political events and human expressions and cultural activities that are unlikely to survive in the places they’re being created. It’s a way to preserve human patrimony.”

For librarians like Hazen’s Middle Eastern specialists, salvaging documents is more than an adventure: It’s a rescue mission.

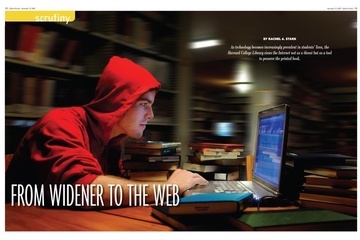

Walking back into his office, Hazen tells me that preservation often means digitization. Over the past decade, Widener has undertaken a major online exhibition project. We lean over the many piles of paper on his desk, and Hazen opens a single screen that contains links to 17th-century Harvard, Latin American businesses, and the Civil War. These open collections, designed for university research and teaching, allow library-users to view rare artifacts and manuscripts online, and then request real copies from Widener’s Depository.

Some of these web collections attempt to restore physical collections that have long been dismantled or dispersed; the exhibit “The Lost Museum of Harvard Dentist School” includes records of the world’s largest tooth, once displayed at the museum. These collections do not require Harvard identification for access, making them available around the world—and in places where physical documents might not survive.

Hazen’s team does not necessarily seek to replace print materials with digital ones; rather, digitization ideally should draw attention to materials that cannot, for logistical reasons, be physically displayed. Hazen references a California collector who sold the library 20,000 individual zines (which are typically short, self-published works reproduced via photocopier)—unsorted in boxes. Though the library’s Pforzheimer fellows (graduate student interns) spent several months sorting through the zines, Widener has not yet found a way to showcase such a large collection. In the mean- time, one fellow started an online blog analyzing the zines.

Widener has also embarked on recent initiatives to compile websites—especially ephemeral ones—in archives. “We’re not collecting representations of the digital world the way we collected representations of the print world,” Hazen says.

Hazen’s favorite collection, though, remains a physical one: the Santo Domingo Collection, acquired from a private Columbian collector obsessed with the history of European sex, drugs, and rock and roll. The collection contains everything from 16th-century medical treatises about opiates to French pulp novels from the 1950s.

“The rock and roll part of it went to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland,” Hazen explains. “But we got the sex and drugs.”