The recent visit of South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley as Harvard Foundation guest lecturer provided Harvard students and faculty with an opportunity to learn first hand about her decision to do something that none of her predecessors had done: remove the Confederate battle flag from its prominent display on the South Carolina Capitol grounds. This act was a powerful and emotional statement for African Americans throughout the nation, particularly multigenerational black Americans, who have lived under the terror of this symbol of racial hatred in America, and the emblem of America’s notorious white terrorist group, the Ku Klux Klan.

Whatever Governor Haley’s previous political position was on the removal of the Confederate flag, she was able to persuade members of a resistant state legislature to support her and get the job done. Many Americans, particularly recent immigrants with little appreciation of the black American struggle, do not understand the hierarchical significance of the outlawing of the Confederate flag to African Americans. They have never driven through the South and been followed menacingly by a truck decorated with Confederate flags or had the flag placed in their yard next to a burning cross.

Unfortunately, in politics, as in other spheres of life, tragedy often motivates change. There is no doubt that the impetus for Haley’s historic act in June 2015 was the unconscionable massacre of nine kindhearted African Americans, who were simply “praying while black” in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, when they were shot dead by a white American terrorist who embraced the Confederate flag. The state of South Carolina and the nation mourned their loss, and both Haley and President Obama rightly sought to heal and unite black and white Americans in forgiveness and peace.

Following Haley’s public “conversation” with students at Philips Brooks House, and her later lecture at Winthrop House, numerous students asked me about the history of the Confederate flag at Harvard. This subject was also raised by a number of former Harvard College students at a recent Harvard Black Alumni meeting. To the chagrin of many black alumni, there were also controversial displays of the Confederate flag at Harvard University in the 1990s by misguided students. The flags tore the campus asunder, and even ‘til this day, they inspire bitterness and anger.

For those of us who are committed to improving relations between different racial and ethnic groups, the Harvard Confederate flag conflict was an agonizing setback and a lesson for us all. The incident sparked anti-racist protests, “sit-ins,” and “eat-ins” in the College dining halls, and even a 100-student protest march against the masters of Kirkland House. Many at the time believed that the era of racially provocative symbols had passed, and that the enlightened students in the hallowed halls of Harvard would never raise a flag of racial hatred and divisiveness in the Harvard community. They were wrong.

The Confederate flag conflict demonstrated that even at Harvard University, some students and staff are insensitive to the fact that “black pain matters.” We can learn more about race relations in America from this case of inter-ethnic conflict and racial insensitivity among “the best and brightest.” The challenge is that some who engage in racially offensive acts against African Americans, even at universities, often do so with impunity and the indifference of their associates. They are comforted in the knowledge that they pay no price for racial humiliation and abuse of African Americans. University administrators who reward silence and punish exposure of instances of racial maltreatment of black Americans are at some level complicit, and profoundly racist.

Teaching the history of the Confederate flag at Harvard may serve to enlighten us about our past and present status of race relations. Harvard records show that Confederate flag displays at the College have occurred at various times in the past. In 1948, Harvard College student Louis B. Du Pree '50, from Greenville, North Carolina, publicly displayed the Confederate flag from his window at Kirkland House. This incident led to protests from Harvard’s few black students (only four black students were admitted to the Harvard freshman class that year). Later, in 1952, a cross was burned in front of Stoughton Hall, where the 11 black members of the Harvard class of 1955 lived.

In the spring of 1990, Jon P. Jiles, a Leverett House student, displayed a Confederate flag outside his window as a symbol of his “ethnic identity” and “heritage.” A number of African American students and tutors in Leverett House requested a meeting with the House masters John E. Dowling and Judy Dowling to discuss their disapproval of the hanging of the Confederate flag in their residence hall, and how they were aggrieved by the presence of this symbol of racial terrorism and hate in the Harvard community. Dowling, a distinguished professor of neurobiology, said later at a meeting with his fellow House masters, “We live in a community, and if one person displays something that offends everyone, it should be taken down." At the insistence of the Dowlings, Jiles removed the Confederate flag, and Leverett House restored civility and trust among its residents of all races with no further disturbance.

Similarly, Briget L. Kerrigan, a Virginia transfer student in the class of 1991, displayed her Confederate flag prominently in the entry area of Harvard’s Kirkland House as a symbol of her Southern heritage. Kerrigan, a highly vocal student who said at the time, "I was born in the South. I was born a rebel," argued that the Confederate flag is a symbol of "Southern honor, grace and dignity."

In contrast to the Dowlings, Kirkland House Masters Donald H. Pfister and Cathleen K. Pfister permitted Kerrigan’s Confederate flag to remain hanging in prominent display in the entryway of their House for months, in spite of emotional pleas from Harvard’s minority students to take it down. The masters of Kirkland House maintained that it was Kerrigan’s right of free speech to display the Confederate flag. When African American students countered that the display of a symbol of hatred and human slavery was not speech, but an act or behavior, the Kirkland House masters still refused to remove the Confederate flag from the College residence hall.

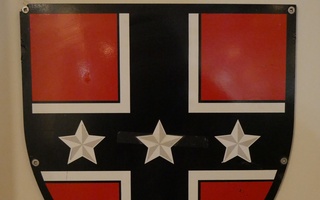

Some asked whether the House masters would permit a Nazi flag to remain displayed in the entryway of the residence hall under the free-speech rule. (Outraged by the vapid free-speech defense in the refusal to remove the Confederate flag from the residence hall, one black student drew a swastika on a piece of cloth and displayed it in her dormitory window—the student had no Nazi flag. Within a short period, Harvard officials entered her room and took the swastika down, but left the Confederate flag in place.) Even fellow House masters, such as Eva S. Jonas, a master of Adams House, urged the removal of the Confederate flag from Kirkland House, calling its display "unfortunate and unnecessary, some sort of immature behavior." University President Derek Bok also voiced his objection to the Confederate flag display.

One large, anti-Confederate flag protest march ended in the Kirkland House dining room where more than one hundred black students and their allies gathered in hopes of persuading Kerrigan and the Kirkland House masters to take down the offensive flag. I was asked by the President’s office to attend the meeting to keep the peace. It was standing room only, and students from Harvard College and Harvard Law School gathered at dining tables and around the walls of the Kirkland dining hall, some singing “We Shall Overcome.” The atmosphere was somber, and many students were despondent, even angry, some describing the House masters as “racist.” The student speakers, including Kirkland House representatives, each spoke with calm civility about why they wished to remove the divisive Confederate flag from public display in the Kirkland residence hall.

Black Student Association president Micah Nelson spoke eloquently about the hateful nature of the Confederate flag and why it was offensive to African-Americans and other Americans of goodwill. She appealed in a very measured tone to Kerrigan and the House masters, who were present at the dining hall gathering. Kerrigan did not budge or make any comment to Nelson’s plea. A number of black students made emotional pleas to the House masters to use their power as appointed residence hall directors to take down the hateful and hurtful symbol, but sadly to no avail.

Particularly impressive was African-American student leader, Nigel Jones who delivered impassioned remarks about the “importance of respect for the feelings of fellow students, and making an effort to understand and appreciate the feelings of our fellow humans regarding symbols and actions that offend.” At one point, Jones said to the gathering, “People will tell you that the flag means a lot of different things. It stands for white supremacy and it stands for slavery. It is a symbol of the white South." Jones came to Harvard from Weston High School in Weston, Massachusetts, where he graduated valedictorian of his senior class. His father, Tom Jones, had been a prominent civil rights activist as a student at Cornell University in the 1960s. Nigel Jones went on to graduate from Harvard with honors and entered the United States Marines Corp as a commissioned officer, where he served with distinction for a number of years under “the Stars and Stripes.”

In the end, Bridget L. Kerrigan achieved her apparent aims and offended African-Americans and others at Harvard who believed in a college community of goodwill and mutual respect among persons of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The masters of Kirkland House ultimately declined to take the Confederate flag down, and to the humiliation of Harvard’s black community, the racist symbol of Kerrigan’s white southern “heritage” remained displayed in the entryway of Kirkland House until she graduated and moved back to Virginia.

Professor John Dowling is remembered to this day by many of Harvard’s black alumni as a compassionate and racially sensitive House master, who respectfully removed the offensive Confederate battle flag from Leverett House at the request of his students and colleagues. Kerrigan is remembered at Harvard for what many viewed as her arrogance and disregard for the feelings of the vast majority of her diverse peers — peers who passionately appealed to her to remove the ugly Ku Klux Klan symbol of American terrorism and hatred from their college, and restore an atmosphere of racial harmony at Harvard.

Haley’s historic act of removing the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina State Capital has inspired legislatures and citizens of other southern states, such as Mississippi, to advocate for removing the racially divisive emblem from their state flags. The achievement of this aim would mean progress in improving America’s race relations.

Some minority students were concerned that Haley’s visit to Harvard as guest speaker might provoke racially insensitive students to display the Confederate flag in their residence halls. Thankfully, this did not occur. Perhaps we have reached a level of racial understanding at Harvard where students and House masters realize that the display of the Confederate flag is hurtful to African Americans.

At the Kirkland House Confederate flag protest, I made the following statement:

“There is but one flag that historically and currently represents the United States of America and binds the people of our nation together as one, ‘The Stars and Stripes.’ At this College and throughout this country, we should raise and pledge allegiance to this flag only.”

Dr. S. Allen Counter Jr. is the Director of the Harvard Foundation and a professor of Neurology at Harvard.

Read more in Opinion

The Cult of MotherhoodRecommended Articles

-

MAIL:To the Editors of The Crimson: I would like to comment on the Confederate flag in the window of Matthews

-

Dixie Flag Flies Over YankeelandYesterday was General Robert E. Lee's birthday anniversary and ten Staunch southerners from Kirkland House didn't let it pass unnoticed.

-

Traveling While BlackIf you don’t ever have to think about the thing, how can you not spend all your time feeling thankful that you don’t have to think about the thing, instead of telling other people they are silly for thinking about the thing? But still, how could you?

-

What's In A Shield

What's In A Shield -

Our Own Little War

Our Own Little War