A frayed French almanac, ornate, gold etchings lining the edge of its leather cover. The diary of suffragist Susan B. Anthony, blue ink splattered across its gossamer pages. A dusty vinyl record of the Grammy-winning hiphop standard, “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.” A 19th-century drum microscope, years of use having chipped away at its silver coat. It’s an eclectic set of items, spanning generations, continents, and lifestyles. And yet, all share one common quality: Each calls Harvard’s campus home, nestled away in one of the University’s several libraries and archives containing special collections.

Established at different points during the 20th and 21st centuries, these collections stand as a testament to the depth and breadth of scholarship that the college has long fostered. From the artifacts of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments to the poems of Emily Dickinson in Houghton Library, to the feminist art on the history of women in America in the Schlesinger Library to the vinyl records of the Hiphop Archive, the thousands of objects are as numerous as they are diverse. In allowing both College students and outside researchers to come face to face with such historically relevant primary sources—to examine the crinkling pages of artist Walter Crane’s illustrations or peruse the original poetry of John Keats—these collections not only promote rigorous study, but also serve as a conduit between the past and the modern world.

And yet despite the incredible academic opportunities these collections provide, they still struggle to attract the attention of much of the undergraduate population. Recently, collection teams have turned to technology to better engage with the student body, utilizing social media and digital archives to promote both aspects of their collections and potential learning experiences within the libraries. These efforts have proved quite successful, but regardless, the mere existence of the collections bodes well for Harvard. These special collections do more than bolster research opportunities; they preserve and illuminate the stories of the past.

DEBUNKING THE INACCESSIBILITY MYTH

While these unique collections are open for student use, outside researchers and graduate students continue to be the primary patrons. Brionna M. Atkins ’16, a research assistant at the Hiphop Archive, suggests that the imbalance in researcher and undergraduate engagement stems from how many undergraduates simply don’t realize these spaces exist, let alone that they are open to them. “There’s a certain subset of campus that knows about [the Hiphop Archive], and the people who know will come to events,” Atkins says. “But I don’t think most [undergraduates] are aware of it.” For those who are aware, like Atkins, interacting with the archives presents a chance to combine scholarship with personal interests. “It doesn’t feel like work to me. I’m a Sociology concentrator, so I’m combining things I’m working on academically with what I listen to in my free time,” she says.

Since College student attendance has consistently remained lower than that of researchers, several librarians have expressed interest in drawing more undergraduates to these special collections. “I don’t think we’re underutilized, but I do want Houghton to be utilized more,” says Thomas Hyry, the librarian of Houghton Library. “In addition to supporting advanced scholarship, we want to see Houghton as an intellectual center for undergraduates on campus. It’s important that they know about us and that we’re here to help.”

Marilyn Dunn, executive director of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library, agrees. “We would love to see more students come to the library,” she says. “We have graphic novels, rare books, inscribed copies, a number of workshops—lots of things students would particularly enjoy.”

Both librarians and administrators understand that the notion of “rare books” or “specialized collections” might potentially intimidate undergraduates from stepping inside the libraries, and their efforts to promote their material are often centered around dispelling that idea. “We really want undergraduates to see Houghton as their library as well,” Hyry says. “Over the last generation, things have really changed here. The attitude that this is an undergraduate’s library was tolerated maybe a generation ago, and then a generation before that actively discouraged, but we’ve really turned a corner.”

The online registration process required to interact with certain library collections can also act as a deterrent to interested students. Unlike in the cases of Widener and Lamont Libraries, undergraduates cannot simply walk into Houghton; instead, they must first fill out a brief form on the library website. “The library is a real intellectual nexus. To do research here, you have to go through a registration process, simply because we need to know just who’s inside,” Hyry says.

Marcyliena Morgan, executive director of Harvard’s Hiphop Archive and Research Institute, says that opening the collections to all undergraduates without screening them risks damaging, or potentially removing, the material inside. “The first hiphop magazine, ‘The Source,’ began here,” Morgan says. “We used to have every issue, but unfortunately, there were some people who felt they should have them more.”

Though the libraries encourage undergraduates to engage with their material, they understand that drawing the same numbers as Widener and the Natural History Museum libraries just simply isn’t feasible. “We’re different than a natural history museum; we just don’t have the infrastructure to have 150,000 people a year. It feels quite crowded when we have 40 people in our permanent exhibit,” says Dr. Jean-François Gauvin, administrative director of the CHSI. “We know our niche: teaching and research and engaging with the Harvard community.”

#REACHINGOUT

In recent months, the special collection teams have turned to technology to spread awareness of their materials. Several libraries have begun creating digital versions of various letters, books, and drawings in hopes of piquing the interest of Harvard undergraduates. There’s a growing trend in the idea that if students aren’t coming to the collections, then the collections will come to students. “We’re digitizing the larger, significant collections—Harriet Beecher Stowe, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Dorothy West—so if students can’t get here, they can still get the resources,” Dunn says, in reference to the Schlesinger’s materials. “We’re compensating for the fact that our materials do not circulate, because we want them to be available.”

Houghton Library has even turned to social media to share its material with the academic community, becoming one of the few Harvard collections with an Instagram. Using hashtags such as #watermarkwednesday and #theatrethursday, Houghton routinely posts images of illustrations, photos, and book covers from within its collection. “Social media platforms allow us to promote awareness of Houghton’s collections and services to new audiences,” Hyry says. “Maintaining an active presence on social media provides opportunities for students to learn from our collections in new contexts and, ideally, draw new researchers to the library.” And the strategy seems to be working: Hyry notes, “If you compare the number of undergraduates using Houghton’s reading rooms from last September to this September, we’ve seen a 46 percent growth.”

Other libraries use word-of-mouth tactics to draw Harvard affiliates and outside community members to their collections, often focusing on engaging patrons once they’re actually in the space. “We have guided tours with faculty and students, in addition to hands-on sessions in the library where we bring some of our objects out so people can interact with them,” Gauvin says. Recently, the CHSI team has turned to innovative ways of engaging students, including creating interactive games. For their exhibit on the Rawson Electrical Instrument Co., CHSI volunteers handed guests colorful cards with names and descriptions of famous scientific figures then encouraged the visitors to peruse the gallery in search of what each card was referencing. “The idea was to have people roam around the exhibit, learning more about the company in a fun way,” Gauvin says.

Read more in Arts

Hear Me Out: Beach House, 'Elegy to the Void'Recommended Articles

-

Harvard Day at Fenway CourtMrs. Gardner's art collection at Fenway Court, Boston, will be open to none but students in the University on Wednesday,

-

Houghton Library Abounds In Valuable Old VolumesWith a primary purpose of making the University's rare books "earn their keep" by exhibition to the public eye, Widener,

-

The Elements of Book CollectingT HE book collector's service to the mind of mankind cannot be overestimated. Private collections are a joy to their

-

Navigating the Archives: Houghton Looks To Draw Students

Navigating the Archives: Houghton Looks To Draw Students -

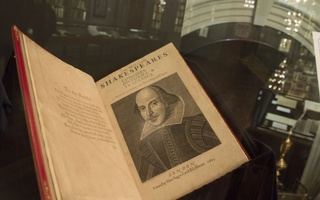

Houghton Library Exhibit Brings Shakespeare to the Yard

Houghton Library Exhibit Brings Shakespeare to the Yard