Zaneta H. Hong, lecturer in landscape architecture, calls the central studio in Gund Hall the “heart” of the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and for someone regarding the space for the first time, the description holds true. The space is dominated by a five-tiered collection of desks, each one designated for a specific graduate student’s personal use. A clear span roof and large windows let in rays of light that seem to emphasize the concept of the studio as the core of design education.

{shortcode-03e08eec978a0d7d313844e6e84155edec6bd90a}

Behind the central studio, however, a much smaller, much less formidable space serves as a classroom for a small group of students. This is the HILT Room, a new space at GSD meant to revolutionize how design is taught. The acronym refers to the group that funded the space: the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching. While it is located in Gund Hall, the HILT Room primarily serves undergraduates—specifically, those pursuing the new architecture studies track in the History of Art and Architecture Department.

Established in 2012 and administered by both the HAA Department and GSD, the architecture studies track is itself divided into two branches: history and theory, and design studies. The former emphasizes the study of the history of architecture; the latter, contemporary theories and applications of design. K. Michael Hays, a professor of architectural theory and associate dean for academic affairs at GSD, believes that the establishment of the architecture studies track filled a conspicuous gap in the liberal arts curriculum at Harvard. “[The HAA Department and GSD] have often talked about how disappointing it was that Harvard, who has one of the strongest and progressive liberal arts curriculum, never saw architecture as a liberal arts pursuits,” Hays says.

Still, Hays admits, the nature of architecture as an academic discipline makes it difficult to teach in the non-pre-professional context of a liberal arts college. “Because architecture has a very technical dimension, to teach it as a liberal arts study requires a little more effort,” he says. To address this challenge, the track forged a unique connection with the GSD. “What we decided was that by doing a jointly administered program, we would bring the expertise of both departments to bear.”

Students and faculty members associated with the track acknowledge that close ties to a profession, as well as to the pre-professional program at GSD, make it difficult for the program to strike a balance between the academic study of architecture and its technical application. But the achievements of the fledgling track suggest that the struggle yields success. Since its establishment, the program has provided a niche for students whose interest in architecture had previously been unaddressed by the college, and has served as a frontier for the promotion of a philosophy that seeks to broaden people’s ideas about the scope and application of architectural knowledge.

OFFICE SPACE

At just three years old, Harvard’s architecture studies track is quite young compared to those at most other institutions. Two T-stops away in Kendall Square, the MIT School of Architecture and Planning boasts five tracks within its undergraduate Bachelor of Science in Architecture program. The five-year Bachelor of Architecture program for undergraduates at Carnegie Mellon is accredited by the National Architectural Accrediting Board. These undergraduate architecture programs all feature a studio component—the aspect of Harvard’s architecture studies track that sets it apart from the rest of the HAA Department.

In addition to architecture-related classes in the HAA Department, both branches of the track require students to take two architecture studio courses at GSD: Architecture Studio 1: “Transformations” and Architecture Studio 2: “Connections.” But Professor Hong is adamant that studio courses do not a pre-professional program make. “It’s just meant to give a very enlightened preview of what an architecture program should be,” she says.

The logistics seem to support Hong’s opinion; the studio courses required by the architecture studies track only meet for six hours per week—half the time of most studio courses at GSD and of those at most nationally accredited undergraduate programs.

Hong, who teaches “Transformations,” says the studio utilizes diagrams and models to help students acquire a perspective crucial for understanding design. “Transformations” is really about developing certain knowledge and language that’s found in architecture,” Hong says. “The way that we do this is through visualization…. A lot of the products that you see from the studio are a lot of physical models, and these physical models are meant to engage a lot of larger architectural concepts—pattern, density, flow.”

According to Hong, the studio courses also provide students with the opportunity to learn the language, the terminology, and the methodology of architectural design. In her opinion, this kind of knowledge provides a solid foundation for a career in architecture, if it is what the student wants, but is by no means valuable only for this purpose.

Jeremy Ficca, an associate professor of architecture at Carnegie Mellon’s School of Architecture, agrees that studio time is essential to understanding architecture on a technical as well as a theoretical level. “[Studio work] begins to establish a way and an instrument to address ideas through the design process. Quite literally, the students are working on projects that become the vehicle to explore ideas,” Ficca says. “The studio is generally understood as being the backbone...the place through which you can...bring what you’re learning in other classes to bear on the ideas that you’re exploring in the design studio.”

For Alaina R. Murphy ’14, the required studio classes were the highlight of the track. “[Studio class] was the defining thing that made it architecture studies instead of HAA,” she says. “I personally wish I had time to do more [studio classes], and I wish there were more offered. One [class that I took] was a construction studio—we were in the GSD and physically making things every week…. We had to use computer software and our own drawings, and in the end we had to produce a structure. We got to use tools, use our hands, and that was something really special.”

Stella Fiorenzoli ’15 would also have welcomed more studio time. “I love to make things, I love to draw, I love the hands-on experiences,” she says. “That ability to go to the GSD and make those things has been met by Harvard negatively. It’s taken as being too pre-professional, but I wish we had more of those experiences.”

For students like Murphy and Fiorenzoli, the pre-professional bent of the architecture studies track, far from undermining its legitimacy, is an asset. In Fiorenzoli’s case, the studio component was the deciding factor that led her to pursue the track. “The studio courses and the ability to make something that comes from yourself...[provide] proof of the theories you learn,” she says. “If the architecture track didn’t have those things, I wouldn’t have applied [to the program].”

BUILDING A RESUME

Architecture studies student Benjamin Lopez ’15 believes that the program’s attempt to reconcile theoretical and technical components has led to deficiency in the latter. “I expected a lot of my courses to be heavily design based and project based so you could build a portfolio,” Lopez says. “I was hoping to come out of Harvard with a few more projects, but what I found was the track doesn’t have too many design courses.”

Though Lopez does not intend to pursue a career as an architect, he is doubtful as to whether his undergraduate experiences would have provided sufficient preparation for an MArch program. “If you want to be an architect and have a comprehensive architecture education, Harvard is not the best place,” he says. “I feel that I don’t have the comprehensive skill sets a lot of students at competing schools do have…. Architecture programs and employers want to see what you’ve done, not your classes.”

{shortcode-7fc0316778863b1b295ff952058c270c3d34fd47}

But how helpful a pre-professional undergraduate program is for aspiring architects remains unclear. According to Renée A. Caso, administrator for academic programs in the MIT Architecture Department, the criteria for admittance into the MIT MArch program are flexible. “I often see and notice that a lot of the students who apply and get into the program do not come from architecture programs,” she says. Caso also stresses that securing admission into a graduate program should not be the only goal of an undergraduate program in architecture studies. “To help students really decide whether or not [architecture] is the direction they want to go in is as equally important as training them for...an MArch program,” she says.

For some Harvard undergraduates, the architecture studies track has achieved this second objective, providing them with clarity about their professional ambitions and reaffirming their love for design. Murphy’s post-graduate experiences make clear that this love need not manifest in the form of a career as an architect. Since graduating in June as part of the first group to complete the track, Murphy has started working at Touch Of Modern, a startup that sells modern design items. “I knew after college that I wanted to be in the design world, but I didn’t know if I wanted to go to the graduate school,” Murphy says. “But one gap that I knew that I had in my knowledge of design was...design in terms of money.” While Murphy’s career has led her away from architecture, she cites her undergraduate studies as being influential in her job choice. “The concentration definitely secured my desire to be surrounded by design and to learn more about it,” she says.

ONE HARVARD

In addition to raising questions about the place of pre-professional studies at a liberal arts college, the required studio component of the architecture track necessitates close ties to GSD. The workshops and materials used by architecture track undergraduates were once used almost exclusively by graduate students. While the undergraduate track undoubtedly benefits from the wealth of resources available via the school, the connection between the track and the graduate school is not devoid of complications.

“Our interactions with the GSD are the highlight, but it’s not so fluid and seamless as it would seem,” Lopez says. “I wish we were more immersed in graduate classes, [and] I think we should take more…. The GSD is definitely opening their doors, [but] I guess you just get greedy and ambitious and wish the doors were more open.”

Fiorenzoli is thankful for the relationship between GSD and the History of Art and Architecture Department. “The whole environment gave me a really nice glimpse into the graduate school for architecture,” she says—a glimpse that has strongly influenced her decision to apply to graduate design school. However, she characterizes her personal connection to GSD and the HAA Department as unequal and acknowledges that the imbalance can be problematic. “I’ve made some really close connections with faculty at the GSD but less so with the HAA Department,” she says. “When I was looking at who would be my senior adviser for my thesis, I didn’t really know anyone at Harvard.”

Hays, too, admits that a seamless connection between GSD and the architecture studies track has been difficult to achieve. “[President Drew Faust] had a slogan...of ‘One Harvard,’” he says. “Her plan has been to bring together the different schools, including the graduate schools and the different departments in the College…. Despite the power of that plan, there’s such a built-in inertia to the institution.”

According to Hays, this inertia also contributed to the difficulty of making the architecture track a reality—an roughly three-year process that required an intensive approval process and concerted efforts on the part of both GSD and HAA faculty members. “The school as an institution has policies made to resist…connections and innovations,” Hays says. “It took a group of faculty working from the ground up and pushing it through the FAS processes…. There was a lot of emphasis on the combined efforts of two schools.”

ARCHITECTURE AS A MINDSET

Though many architecture studies students seem to view the track as a means of realizing a career in design, Hays is adamant that the program aligns with Harvard’s commitment to providing undergraduates with a liberal arts education—one that does not feed into a specific career. For Hays, architecture is not merely a discipline but a mindset. To study architecture is to develop a way of thinking and of seeing the world that is distinct from that cultivated by other areas of study.

“Architects learn different ways of representing data. We can represent data in a very graphic way rather than numerically and textually,” he says. “Imagine someone going into biology with the ability to represent the interaction of complex systems in a different way than a normal biologist would represent it…. It would expand the kind of way you can learn about things. The hope is that [studying architecture] will contribute to an expanding potential of thoughts in other fields.”

Professor Ficca agrees that the study of architecture has implications far beyond the acquisition of technical, applicable knowledge. “I know it’s a very simplistic analogy saying [architecture] is the merging of the arts and sciences, but despite being a technical field of study and practice, it is implicitly a cultural act.”

{shortcode-6c88d1d8ddb37f9769476d6ccc9e4b7bf210a012}

Fiorenzoli affirms that the study of architecture informs and is connected to other areas of study. A joint concentrator in music and architecture studies, Fiorenzoli sees the disciplines as deeply connected and is currently at work on a thesis that combines the two. “Architecture and music have very similar languages,” she says. “Architects will often talk about the rhythm to a façade—how quickly you eyes move across a facade, what are the pattern of the movements on the building, how do they interact…. The two worlds are definitely related in that sense.”

Meanwhile, Abigail Harris ’16 hopes that her design training will enable her to combine her interest in architecture and her secondary in women, gender, and sexuality studies in a socially impactful way. “In WGS, we see that all institutions are constructed by…heteronormativity,” Harris says. “I’m interested in seeing how we can construct some of those social implications in our designs.”

CONSTRUCTIVE CHANGE

Ambitious philosophy aside, the architecture track is young, and students and faculty members alike acknowledge that there is room for improvement. Harris feels the track still doesn’t have a specific focus and lacks complete definition.“I wish that I wouldn’t be such a newbie to the program because it’s definitely only getting up and running, and the classes that we have to take aren’t exactly defined,” she says. “Right now, I don’t have a really specific focus on my architecture studies.”

Hong cites a variety of ways in which the track could be improved: “There needs to be a much larger infrastructure, more staff, more student interest.”

Yet, students find plenty to praise about the track—notably, its tight-knit community and the specificity with which the program caters to their interests. Harris admits that the existence of the track cemented her decision to go to Harvard. She had been considering Princeton, which is well known for its undergraduate program in architecture, but chose to attend Harvard after discovering that the architecture studies track was being implemented.

Also attractive to students is the relatively small size of the track—out of the 70 sophomores that declared HAA concentrations last November, nine opted for architecture studies. This results in smaller classes and more personalized teaching. Lopez recounts a time when the students expressed disappointment that none of the course offerings for a particular semester dealt with modern art. Hays heeded their complaints and was able to implement a new course about modern architecture for the following semester.

Additionally, students are excited by how the newness of the track enables them to have a real impact on its development. “That ability to control what will happen for the next generation—that is something I’m very thankful for," Fiorenzoli says.

It is this commitment to improvement that breeds positivity about the track’s future. Hays hopes the track can expand beyond architecture into urban and landscape studies. Fiorenzoli, too, has a grand vision for it. “I see it as being its own concentration,” she says. “I see it expanding in numbers full of students who come here knowing that there is an architecture track, knowing there is a space for them.”

Even as it endures growing pains, the architecture studies track seems to be in the midst of a multifaceted bloom, simultaneously opening Harvard’s doors to students who might previously not have felt that the school’s definition of liberal arts included a place for them, and encouraging the development of a different way of thinking about the nature of architecture. “Right now, architecture is a profession,” Hays says. “I would like to define it more as a discipline and a mode of knowledge.”

Read more in Arts

Fall TV PreviewRecommended Articles

-

New GSD Program Aims To Get More ArchitectsBritish-based architectural firm RMJM recently donated $1.5 million to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) in an attempt to increase

-

Calvin Klein Shares Perspective on Design at GSD

Calvin Klein Shares Perspective on Design at GSD -

Design School Building Draws Praise, Except For the Desk Space

Design School Building Draws Praise, Except For the Desk Space -

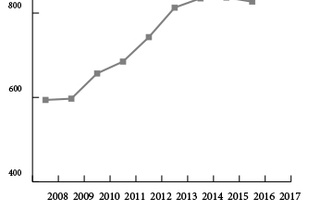

Graduate School of Design's Enrollment Soars Skyward

Graduate School of Design's Enrollment Soars Skyward -

Female Faculty at GSD Sign Statement Against Sexual, Racial Misconduct

Female Faculty at GSD Sign Statement Against Sexual, Racial Misconduct