No one wants to talk about Asian-Americans in the affirmative action debate. With the recent ruling that upheld Michigan’s ban on affirmative action, the divisive pushback by Asian-American political leaders and interest groups regarding the reinstatement of affirmative action in California, and the unsettling “Harvard Not Fair” campaign that seeks to capitalize on the insecurities of rejected applicants based on race, one thing is clear: Asian-Americans are left to converse in the backroom during any nationwide discussion on affirmative action.

As Asian-Americans, our placement in the affirmative action debate puts us at an unfair disadvantage against everyone but ourselves. Why is this? Because people on both sides of the affirmative action debate oversimplify the Asian-American experience to suit their needs. Asian-Americans are cast as the “unexplained minority exception” in the cost-benefit analysis of who “wins” and “loses” in affirmative action.

Many today feel uneasy when talking about Asian-Americans and affirmative action—and understandably so. In an education system that witnesses Asian-Americans comprising 38 percent of UC undergraduates and boasting the highest high school graduation rate of any race in the country, many speculate: Are there “too many” Asian-Americans in our education system today? Is it a disadvantage to be Asian-American in the college admissions process? Is it harder to get in?

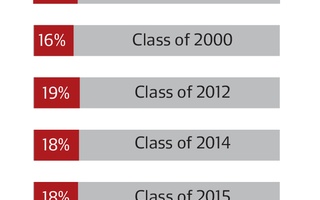

Asian-American students in today’s education system share the anxiety. Princeton researcher Thomas Espenshade and Alexandria Walton Radford of RTI International found that Asian-identified students had to score 140 points higher on their SATs to gain admission to prestigious colleges compared to white students. Espenshade’s statistics are even more striking when comparing the admission rates and test scores of Asian-American students to students of other minority backgrounds.

But instead of constructing an objective reality of the college admissions process, Epenshade and Radford’s statistics have intensified competition among minority students who have no choice but to view college admissions as a zero-sum game. The statistics have diverted attention from the greater issue at fault: a debilitated education system that fails to account for racism, historical oppression, and ethnic diversity.

When looking closely at the anti-affirmative action legal effort Harvard Not Fair, one thing becomes clear: It did not originate from the Asian-American community. Lawyer Edward Blum, who launched Harvard Not Fair and its two sister websites, UW Not Fair and UNC Not Fair, is a veteran opponent of affirmative action. Blum uses stock images of Asian-Americans as racial mascots with the inciting lines, “It may be because you’re the wrong race.” The implication is clear: this exploits the insecurity of Asian-Americans during the college admissions process in order to carry out an attack on affirmative action.

{shortcode-d39f01ba9819849d7b8c3476452b50d1bc8ce783}

Using Asian-American faces and stories in anti-affirmative action efforts unfairly creates competition and division among minority communities. This year, three Asian-American legislators withdrew support for the California affirmative action Proposition 209 after public criticism from the Asian-American community. In response, a number of black and Latino lawmakers and interest groups have withdrawn endorsements for Senator Ted Liu, a Chinese-American facing another Democrat in his congressional race. Black and Latino assembly members also withheld votes from unrelated legislation regarding the state’s carpool system by Assemblyman Al Muratsutchi, a Japanese-American Democrat from Torrance.

The United States is quickly becoming a country with a majority-minority population, but white students still comprise over 60 percent of the college student population. As minorities, why do we have to fight over spots in the college admissions process when the “majority” refuses to budge in the first place?

The view of Asian-Americans as a “privileged minority” ignores the internal class differences that exist among sub-groups under the Asian-American umbrella. Southeast Asians drop out of high school at alarming rates: Nearly 40 percent of Hmong Americans, 38 percent of Laotian Americans and 35 percent of Cambodian Americans fail to finish high school. These sub-groups similarly face alarming percentages of poverty well above the national average, with Hmong Americans displaying a of 37.8 percent poverty rate—the highest among all sub-groups within the Asian-American community.

We as Asian-Americans cannot afford to pit ourselves against other minority groups by buying into rhetoric of college admissions as a zero-sum game. We cannot subscribe to the idea of the “Asian-American whiz kid” and disregard the significant disparity that exists within groups of the larger Asian-American community. We cannot ignore individuals who, in spite of identifying as Asian-American, still struggle to obtain a higher education and better future.

We cannot let the anti-affirmative action debate, framed by those who have historically benefitted from the current education system, rupture our solidarity with other people of color.

Hand in hand, we as Asian-Americans and other minority communities must together frame the affirmative action debate among ourselves.

It is up to us, not them.

Bernadette N. Lim ’16, a Crimson editorial writer, is a joint human evolutionary biology and women, gender and sexuality studies concentrator in Dunster House. Kirin Gupta ’16 is a joint social studies and studies of women, gender, and sexuality concentrator in Winthrop House. Eva Shang ’17, a Crimson editorial writer, lives in Canaday Hall.

Read more in Opinion

Hatred at HarvardRecommended Articles

-

The `Model Minority' MythS OMEDAY the press will understand. Then everyone can understand that not all Asian-Americans are academic superstars. Then they will

-

I Am Not a Model MinorityThe model minority myth has done nothing but strip me of my humanity.

-

Investigating Harvard Admissions: The 1990 Education Department Inquiry

Investigating Harvard Admissions: The 1990 Education Department Inquiry -

More Nuance in Affirmative ActionWhile we disagree with the objective of this lawsuit, we believe that claims of discrimination against Asian-Americans do justify greater scrutiny of Harvard’s admissions process.

-

Why Asian-Americans Are Not a Model MinorityIt is apparent that Asian-Americans are like any other ethnic group in the United States: diverse and hard to generalize, and faced with stereotypes and discrimination. To use William Petersen’s terminology, we are not a “problem minority.” But nor, are we a “model minority.”