On the trade-floor we knew within seconds that something unusual was happening. The first word came from Kevin York, my friend at Eurobrokers, who shouted over his squawk-box. “Steve Steve Steve! There’s paper flying out of the other tower! We’re getting out. We’re getting out!”

“What? What’s going on?”

But he had already gone.

Traders were standing up, puzzled. “Hey guys, the Cantor screens are down. What’s happening?” We switched the televisions to CNN, but were too quick for them: there was no news there yet. People were jumping up all over the floor, curious, gathering around the TVs. A yell from the Treasury trader: “Something is happening! Buy everything!”

A picture of the North Tower came on screen, smoke steaming out. We could see faces in the windows. Someone pointed to the Cantor floors and said blankly, “Sean Lynch is up there.” On my desk, Sean’s squawk-box had started emitting static. I turned it off.

The second plane went in. “Did you see that? Hold on, did you see that?” We were scared now, no longer curious. Trading stopped, and as the South Tower collapsed, we evacuated our building. I hurried home, flinching as the fighter jets screamed high above, and headed to the Sheep Meadow in Central Park, where I lay on my back in the bright sunshine, holding tight to the grass. There, no buildings could fall on me.

Four years later, I sat on a different trade-floor, in a different city, surrounded by the same landscape of traders, squawk-boxes and TVs. This time we were not ahead of the news. “Breaking story at Aldgate station. There have been several loud explosions reported on the tube network.” Relief: “The explosions were caused by a power surge on the Underground grid.” But then: the picture of the bus, with its roof grotesquely peeled off. “That is not a power surge,” someone said starkly beside me. A familiar visceral sickness swept over me, as the trade-floor emptied and I started a second walk home across a shut-down city, two daughters now waiting for me.

Then, one year ago, on a third trade-floor, in a third city: “Reports are coming in of explosions at the finish line.” Panic once again twisting in my gut: can this be happening again? Where is my wife? Where are my daughters?

Last spring, two weeks before the marathon, I spoke to my Harvard class about 2001. It is a story that is hard to tell. Kevin called me at 8:50 a.m. when the first plane went in, so he had 15 minutes until the second plane hit his tower, and an hour until it collapsed. Eighty-six floors to descend. We received details of his last movements from others. Halfway down, the loudspeaker announced that the building was secure. Kevin went back up to the office; others continued on down and survived. Even then there was a chance. After the second plane hit, Kevin was last seen by his colleague Brian Clark on the 81st floor, helping a struggling woman upstairs away from smoke. Clark went down through the smoke to safety. In the North Tower, Sean Lynch and his brother died along with 656 colleagues at Cantor Fitzgerald.

I tell my students about the heartbreak of 2001, but I also speak of hope. That September I experienced the remarkable robustness of humanity. On September 12th, much of the city was closed to cars, and New Yorkers flooded into the streets. I wandered with my friends amongst crowds, stunned, but part of a communal statement of being alive. Restaurants were full, streets were packed. We were all New Yorkers and I was safe among them.

The magnificent resilience of the human spirit also manifested itself in London in 2005—“We are not afraid”—and here in Boston last April. Two days after the marathon, I stood in the Garden as the Bruins crowd sang the national anthem, unaccompanied; and I fought back tears as I had fought back tears in the fall of 2001, at funeral services in the churches of Montclair, Morristown, and Princeton. Two days later, after the shelter-in-place order was lifted, Boston erupted into life as New York had done 12 years earlier: students streamed out to bars in Harvard Square; local restaurants overflowed with neighbors and friends.

Twelve years, three atrocities. Three cities, one word. New York, London, Boston, Strong.

Stephen Blyth is Professor of the Practice of Statistics at Harvard University, and managing director at the Harvard Management Company. He previously worked at Morgan Stanley in New York and Deutsche Bank in London.

Read more in Opinion

Russian for Native SpeakersRecommended Articles

-

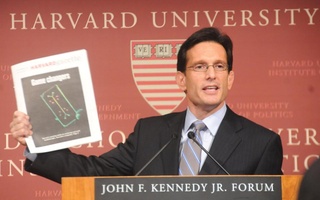

Students Protest Cantor's Speech at IOP

Students Protest Cantor's Speech at IOP -

House Majority Leader Eric Cantor Justifies Budget Cuts

House Majority Leader Eric Cantor Justifies Budget Cuts -

Harvard Students Rally, Protest Budget Cuts to Federal Programs

Harvard Students Rally, Protest Budget Cuts to Federal Programs -

Faust Joins Talks In D.C.University President Drew G. Faust extended a hand to business partners Wednesday to stress the importance of American innovation at Bloomberg Business Roundtable on day two of her Washington, D.C. trip.

-

Final Exam Schedule Posted

Final Exam Schedule Posted -

AIDS Activists Protest at House Majority Leader Eric Cantor's Public Address

AIDS Activists Protest at House Majority Leader Eric Cantor's Public Address