UPDATED 4:39 p.m.

“This is literally the lamest,” a female Harvard student says peering over the computer screen. “Only Harvard kids would use a Google doc to get drugs.”

Like many of her peers, Ava, a senior at the College, spent her high school years racing toward a Crimson-colored finish line. “I was very Type A,” she remembers. “I didn’t experiment really with drugs at all. I guess I drank occasionally, but that was it.” And while some of her fellow matriculates felt paralyzed by Harvard’s ubiquity of excellence, Ava found the superlative level of achievement liberating. “Coming here, I felt like I had this freedom. For the first time, the pressure was off. I could figure out who I am and what I like to do.”

By the end of her freshman year, that revelation meant she was smoking weed regularly and orienting her social life accordingly. “I couldn’t smoke in my room, so I had to go out. I’d call a few friends, and they’d let their friends know.” The invitation was casual and inclusive, unlike much of Harvard’s closed-door drug scene, about which the majority of the College speculates more than it understands. “It was like, ‘Let’s pack a bowl and go to the river’,” she says. When Ava began dealing—“weed and occasionally molly or ecstasy, but mostly weed”—in her junior year, the people who accompanied her freshman year river runs quickly became clients.

Ava is not the first Harvard student to relish the autonomy that begins with high school graduation, although she may be one of the few who began dealing drugs as a result of it. For many, college presents both the resources to experiment as well as the opportunity to do so with virtual anonymity. Ava, like the other drug users in this story all of whose names have been changed, was granted anonymity by The Crimson because she did not want to be publicly linked with drugs.

Greg, a senior mathematics concentrator, also found college to be the ideal time to test drive the drugs about which he had previously only speculated. During his time here he has tried both weed and LSD and does not think his experiences are unique relative to other classmates.

“On the order of 75 percent of my friends have done drugs,” he estimates. Accurate data relating to drug use is notoriously hard to find, but the Harvard University Police Department recorded only three drug-related arrests on campus between the years 2009 and 2011. The disparity between hard facts and rumor concerning Harvard’s drug-using population points to the near impossibility of measuring the scope of drug use on a campus where contraband is more likely to be discussed than directly encountered.

Of course, within certain populations illegal substances are seemingly omnipresent. “If you ask the right questions, you’ll find out that a lot of people are doing drugs here,” Greg continues. “They just don’t talk about it as much as maybe they do at other schools.”

Why that’s the case is mostly a mystery to Greg, but he has his theories. According to Greg and others interviewed for this story, Harvard’s cohort of drug users is concentrated and strongly associated with a handful of social or extracurricular organizations—the Advocate, final clubs, the Dudley House Co-op. While untold numbers of people are doing drugs, a campus-wide fixation on the future makes frank conversations about them rare.

Drugs Should Be Heard, Not Seen

“He took you there?”“Yes! I’ve seen the coke room!”“You don’t know that it’s ‘the coke room,” says the one wearing a spangled dress. It looks like vulcanized rubber crossed with Caesar’s Palace. Her bathroom companion arches her eyebrows before responding. “It’s the coke room,” she says. “And everybody knows it.”

“I would say drugs are way more under the table here and also…kind of sensationalized,” says Ava. She pauses briefly to think of an illustrative example. “I roll my own cigarettes,” she begins—a fact she’ll later demonstrate before we eventually separate into the sunny afternoon. “So I went to a party at the Spee once, and I rolled a cigarette to smoke with a friend. The next week, I ran into one of the guys who was there, and he goes, ‘I heard you came to our party and rolled crack into your joint.’ Suddenly, it was like, ‘This girl’s a bad bitch!’ I thought it was so funny that I didn’t even bother to correct him.”

Even in this retelling of the anecdote, Ava rolls her eyes dramatically. “You can’t roll crack into a joint,” she says. “A rumor like that would never have gotten started at SUNY.”

For Ava, the narrative is representative of Harvard’s relative drug illiteracy—a condition only aggravated by the general student body’s combination of inexperience and omnipresent ambition. “So many people are so afraid of getting their hands dirty with drugs like weed or coke,” says Ava. “There is the sense that if you were caught, somebody could turn you in and that would really fuck things up for you here. [People] are much more willing to just get totally hammered or go out and buy Adderall.”

Harvard’s success-obsessed population plays a factor in James’s assessment of its drug culture as well. James is a sophomore at the College and a self-identified drug user. He first encountered addictive painkillers after sustaining a sports injury while attending a prestigious boarding school. By graduation, he was a habitual user, having experimented with coke, Molly, Adderall and Xanax.

James, echoing Ava, believes that Harvard students have a tendency to be tight-lipped about drug use or avoid drugs altogether, given that pursuing an illegal pastime could have negative effects on their lofty ambitions. “People feel like their future employers and employees, future co-workers or people who are going to help them in the real world go to Harvard,” he says. “It has people feeling that drugs could infringe on their future employment.”

Fear of the ramifications of indulging in illegal substances may contribute to a low level of self-reported drug use on campus. In the 2012 senior survey conducted by The Crimson, over half of the respondents claimed to have never tried marijuana, and more than 95 percent claimed to have never used “hard drugs,” such as cocaine, or “study drugs,” such as Adderall.

Lecturer in economics Jeffrey A. Miron has written about the benefits of legalizing marijuana and argues against stigmatization of drug use. “I believe it is up to the individual to decide whether or not to use drugs, and that there is nothing inherently evil about using drugs,” Miron says.

Miron believes that the negative effects of drug use with which society should be concerned are those that affect others rather than the users themselves. “And I think most people, or certainly a large number of people accept that view for all sorts of other things,” he explains. “We don’t generally take the view that alcohol use per se is evil; broadly speaking, we take the view that driving under the influence is a bad thing, and we want to stop that—we use the law to stop that. But we recognize that when people use alcohol they might misuse alcohol, and that’s not a subject for criminal law.”

While fear of retribution almost certainly plays a role in some students’ decision to abstain, Zoe, a senior at the College who admits to using drugs but declined to comment on the specific drugs she has used, argues against the notion that “Type-A” Harvard students are unwilling to experiment. “In populations of intelligent people, there tends to be a lot of neuroses,” she says. “And people deal with those things in a lot of different ways. Maybe they want to smoke pot. Good for them—if they still get their work done.”

High Functioning

“Do you have an Adderall?” a student inquires. He’s standing with a friend on Mass. Ave., and one of the two is wearing a backpack.

“Sorry. I used my last one to power through this morning.”

“10 mg. or 20?” he presses, drawing out each syllable.

“20,” the friend replies.

“I remember my first 10,” the first muses.

His friend nods.“Sorry, man. Good luck.” “It’s okay. But Lamont without Adderall?” He groans. “That’s hell. That’s just pure hell.”

“I know my body,” James says later on, “and I just happen to be ridiculously high-functioning. I could do four bars of Xanax and be rolling on ecstasy while you had seven beers, and I’d probably be more fine than you.”

But James’ implicit assertion that drug use and high achievement can coexist runs contrary to prevalent stereotypes about drugs at Harvard. For Ava, marijuana’s unpopularity is consistent with what she perceives as the campus’s strictly defined priorities. “Weed doesn’t really have the reputation of being good for your studies,” she says, examining her fingernails.

Still, while marijuana use is not popularly associated with academic excellence, some Harvard students do seek out a different class of drugs in order to stay on top of a demanding workload.

Bennett, a senior English concentrator, first tried Adderall the summer before his sophomore year at the College. In what emerges as a sepia-toned memory, he and a few friends took the pills together. They stayed out talking on a nearby beach until 4 a.m.. The following semester, when a heavy course load and a bout of depression hit simultaneously, Bennett returned to the drug for academic purposes. “I had a really hard time getting through that work,” he recalls. “I had between 700 and 1,000 pages of reading a week.” The pressure was all consuming.

Bennett didn’t find it hard to procure the drug on campus, and when he needed a refill he sought out a friend rather than a doctor. “I don’t know many people here who have ADD, but I know a lot of people who have a prescription,” he says. “I think it’s easy to get. It’s pretty easy to convince someone that you need Adderall.”

After the fall semester concluded, Bennett continued to take the drug occasionally but with less frequency. “I don’t use it that often, but I think it’s been good for me as a way to deal with the academic demands here,” he says quietly. Bennett distinguishes his relatively infrequent Adderall use with “people who take it regularly basically to do all of their homework.” Still, he remains self-conscious about his dependence on a drug to deal with an academic course load that others seem to manage alone. Bennett believes that Harvard students are less likely to use Adderall than other college students: “I think most kids here are already pretty high-functioning, and so they wouldn’t need it.”

But Bennett’s private concern that he is one of only a few relying on Adderall to cope with his studies is called into question not only by oft-cited hearsay, but also by hard evidence. James claims that he frequently sees students taking Adderall in Lamont Library, and a 2011 survey conducted by the Boston Globe found that among an “informal sampling” of students at four Boston-area colleges, 15 percent had admitted to taking prescription drugs—most frequently Adderall—for stress relief, increased focus, and other unintended purposes.

The Social Network

“I’d never do coke,” one says.

“Me neither,” the other replies, outlining her mouth with a wine-colored pencil.

“But you should do Molly. Like, your life will change.”

“Yeah. I’d do Molly.”

Of the College’s general population of hardworking, perennially future-minded students, the number of people James would label as “social” is small. Within their ranks, the number he can identify as active drug users is even slighter. “I think kids will either go through Harvard and not try any drugs or kids will go through Harvard and try most things,” he says.

Zoe, however, disputes the idea that Harvard’s student body can be so easily divided. “I think not being willing to do anything versus being willing to do everything is a false dichotomy. I think there’s a lot more in the middle than you’d imagine. Harvard students aren’t trying to, like, shoot their brains.”

The Harvard Alcohol and Other Drug Services’s characterization of drugs, however, seems to minimize the presence of illegal substances on campus. In an email correspondence with The Crimson, the AODS identified alcohol as the Harvard student’s “drug of choice,” and stated that while “drug use does exist on campus,” it is concentrated primarily “in a small segment of the student population within subcultures of polysubstance users.”

Those members of what the AODS describes as a polysubstance subculture, according to James, comprise a somewhat motley crew. And despite—or perhaps because of—their scarcity, its members know each other fairly well. “I feel like I remember most of the people that I’ve ever smoked with,” muses Ava. Admittedly, the size of the university’s using population lends itself to a degree of transparency. “It’s a small community of people who smoke weed here,” Ava says.

At the very least, these students run into each other in the social spaces that exist outside of Harvard’s immediate purview. As Ava explains, “A party might get shut down in a dorm, but that’s not going to happen at the Spee or the Advocate.”

Zoe also points to certain locations that are associated with specific drugs. “If you’re going to eat mushrooms, then you’re going to go to Mount Auburn Cemetery,” she says. “And obviously final clubs—that’s where the coke happens.”

Zoe recounts recently confronting cocaine during a party at a final club.“I was waiting with my friend for the bathroom,” she explains, “and a line of five guys comes out of the bathroom, and they’re all, like, [sniffing] and putting away, like, their shit. You know what I mean? And you’re just like, all right, okay. I need to pee.”

Drug use cannot be confined to a litany of social organizations or spaces. Greg describes trying LSD for the first time outside of the College’s purview. When he recounts his experience on acid, his voice slows and he mumbles, so it’s difficult to make out exactly what he’s saying. He begins the story over again a few times. In each protracted attempt, he repeats the word “beautiful” so often that it starts to sound a little bit like punctuation.

These are the facts: He bought a small supply with a friend. Together, they walked around the Business School’s campus for a while, and it was beautiful. It was “completely, completely beautiful.” Since then, he’s taken LSD on a single other occasion. “It was really nice,” he says. He’s silent for a while as he tries to articulate how it felt.

This is what he comes up with: “At one point, I had to cross the street, and it was just 100 percent of what I could handle. It was like I was full of this expanding bubble of joy, and I just had to hope I wouldn’t die. I was 95 percent sure I wasn’t going to die.”

Burnt Out

She hugs her knees on the couch, taking a moment to rephrase.

“I know there are a lot of serious drug users at Harvard. But their stories overpower and shade the stories of kids who think they can do it all, and end up in a downward spiral. Some people can use drugs and be OK, but for others it’s debilitating.”

“I think drugs can innovate, and they can hurt,” James says. “It’s completely dependent on the way in which you utilize them. Yeah, there have been times when drugs have fucked me. I’ve quit drugs before. But that’s the thing: It’s taking a risk.”

With perhaps somewhat less bravado, Bennett also recognizes the element of danger inherent to drug use. “I’ve had some bad experiences,” he admits. “I was up for like 60 hours last year writing a long paper, and I couldn’t get to sleep, and by the end of it, it was really terrifying.”

Even in the absence of such immediate side effects, Bennett acknowledges the addictive capacity of drugs. “The effects seem to decrease the more you use it,” he observes. “You get inured to it, and it ceases to become a good tool.” He considers for a moment, and then shares his own sociological diagnosis: “I have a joke that people who need to do Adderall shouldn’t do it...People who have deeper issues that the drug couldn’t address were made more dysfunctional and neurotic because it.”

Margaret E. Crane ’14, the President of Harvard’s Drug and Alcohol Peer Advisors, emphasizes the downside of drug use in an email to The Crimson. “While the Harvard administration aims to respect our independence as intelligent young adults,” she writes, “Harvard’s policy for drugs reflects the fact that most drugs are illegal—largely because those drugs can be harmful to individual students’ health or to the safety of the community.”

And while Ava’s experience with drugs has been largely positive, she does admit that dealing introduced her to their less savory potential.

“I started dealing sort of by accident,” Ava says, recounting the day a friend told her he was trying to cut down on how much he was smoking. “He wanted to sell everything he had and then get out.” His clients—all Harvard students—were less than pleased. They’d been buying from one of their own for months. The pedigree made them feel safe. It made them feel comfortable. It made them buy more.

And so Ava’s decision to start dealing was not as much accidental as it was economic. If she started dealing herself, she could smoke for free. And so the business was born.

She began by buying an ounce of marijuana at a time from “some guy” who wasn’t affiliated with Harvard. She sold to Harvard students almost exclusively—“mostly just people that he used to sell to.” But sometimes Ava would get calls from friends or friends of friends asking for favors. Word of her small operation had traveled, and it didn’t hurt that she had swipe access.

“It’s easier to feel some camaraderie with somebody who is also a student,” she says of her former enterprise. In other words: It’s less sketchy than buying from a guy on a street corner. “I would go to people’s rooms and bring them their weed, and they appreciated it, because, you know, the idea of going off campus felt very unsafe.”

Ava stopped dealing in her junior year, but she’s continued to observe what she sees as a changing landscape of dealers and users ever since. From her perspective, more people are doing molly, but cocaine is as taboo as ever. Adderall is unappealing and “the harder stuff” is all but invisible.

“I’ve never seen cocaine,” confirms Greg. “But I know plenty of people have done coke or have a coke dealer’s number in their phone. To be honest, half of what I hear about cocaine is how expensive it is.” Still, he understands its allure. “Most of my friends, are keeping it together. But things are really hard. It seems like there are a lot of people, like, dealing with stuff—definitely more than they did in high school. People seem really complicated here, I guess I’ll say. Drugs are a way to deal with that.”

A Good Story

“Wait, you have to tell me.”

“No, I really can’t.”

“Seriously, what happened upstairs?”

Ava offers no directive when it comes to drugs. Smoking, she says, is obviously a personal decision. Still, as she reaches into her backpack and fishes out a freezer bag containing loose tobacco and a pack of rolling papers, she can’t quite keep the derision out of her voice: “Harvard students are above recreational drug use,” she observes, “because they’re above recreation.”

But while, according to Ava, Harvard students may consider themselves above drug experimentation, they remain as intrigued by it as any of their peers. Harvard, for all of its institutional grandeur, remains a relatively small school, and stories about drugs tend to be mythologized, maintaining more of a presence on campus than the substances themselves.

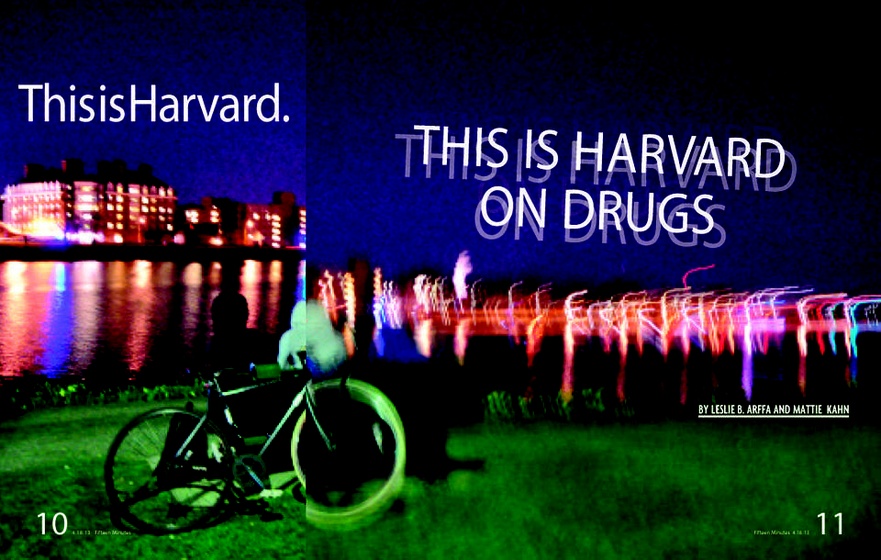

“This is a good story,” Ava says with a rueful smile. “A friend of mine used to do coke a lot. One day, he did some coke and he kind of blacked out. When he woke up, he was in his bed in his dorm room, and he had all these back issues of The Economist around him—open, highlighted and shit, surrounding him.” She wrinkles her nose and grins. “He’d read a dozen back issues of The Economist!” she says. “That’s Harvard on coke, I guess.”

- Rachel Gibian contributed reporting to this article.