This is the third instalment in a series of online-only Roundtables. This new content form from the Crimson Editorial Board seeks to present a diverse array of high-quality student opinion on thought-provoking issues.

If you would like to submit an opinion for this week's Roundtable topic "Should organizations such as the Boy Scouts of America be allowed to exclude a person from membership on the basis of freedom of association?" please e-mail your 200-300 word opinion to hpickerell@college.harvard.edu before Wednesday, Feb. 21 at 6 pm .

More Questions than Answers

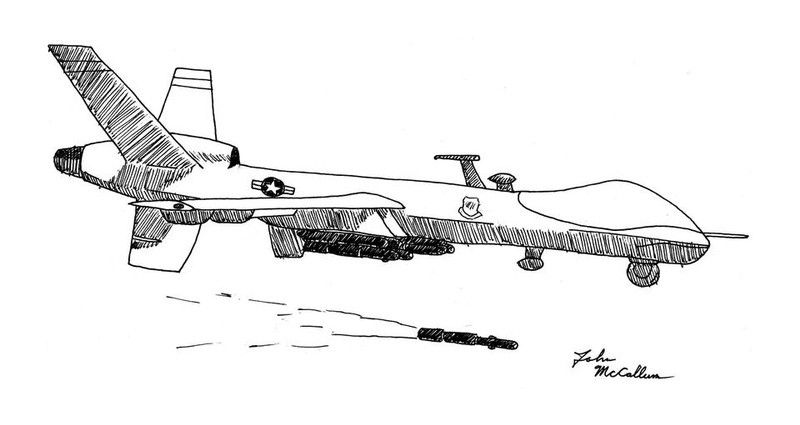

Drones and other autonomous weapons systems have provided several strategic benefits to counterterrorism operations. They allow for nearly unlimited reconnaissance with a level of detail that satellites cannot provide and endurance that human intelligence cannot maintain. They also provide an incredibly valuable tool by pursuing enemy combatants without the risk to human life, a fact which may explain their broad public support.

Yet, drones do not yet follow an established operative framework, which has raised several significant questions about their use. One question involves the rule of law, both in terms of their use in non-combat zones abroad and the current lack of executive transparency at home.

Another question concerns the paradox of intelligence gathering. Since drones inherently depend on human intelligence to confirm opportunities and targets, we can only trust them to the extent that we trust the information which legitimates their use. At the same time, drones may actually increase mistrust of the West and fuel anti-American sentiment, which in turn makes intelligence gathering more difficult.

However, there is another, more significant problem. By removing the human beings from the equation, drones may actually cheapen armed conflict to the point that it becomes a primary option rather than a last resort.

The ultimate question raised by drones then is what happens next—could armed conflict become a preferred option to diplomacy? Could a state of war become a permanent aspect of modern life if unit production is the only cost? And, in the short term, could drones unnecessarily prolong a conflict in which there is no strategic definition of victory, such as a war against ideology? Already, some would argue that the answer is yes.

Yes, drones have provided some significant strategic benefits, but we cannot evaluate their worth until we find answers to the questions they raise.

Raul P. Quintana ’14, a Crimson editorial writer, is a social studies concentrator in Leverett House. His column appears on alternate Fridays.

Drones Require Different Moral Approach

The drone strikes employed by the Obama Administration are "necessary" only insofar as they fit into the moral calculus inherent in being the country's Commander-in-Chief. As weapons of mass terror, drones can hold entire Afghani cities hostage to periods of perpetual fear and suffering. However, unlike an American occupation, they require fewer forces on the ground and thus save American lives. The implicit moral calculation a President must make is how many foreign lives are worth one American life.

A common-sense humanitarian—nay, most Americans—would probably argue that the ratio is one to one. However the logic is different for an American president whose political capital fluctuates directly with his approval ratings. Wars are unpopular. Although the drone campaign is a burdensome evil abroad, it is a preferable domestic political strategy because it keeps young Americans in school instead of on the battlefield.

In this sense drones have been necessary in justifying the War on Terror. Abroad, they have also served various military objectives. As they do not require congressional approval to be launched, drones give the executive branch unilateral direction in ordering and carrying out attacks on targets. The military has pushed for an increase in the use of drones instead of ground troops, members of whom have brought public relations stains to the army by burning Korans and publicly urinating on corpses. In relation to boots on the ground, drones are superior to troops for two main reasons: they are more effective and they minimize the risk of American fatalities.

Drones are not perfect. They carry clear moral repercussions; removing the finger behind the trigger of a soldier in Afghanistan and giving it to a Washington bureaucrat weakens our desire to pursue peaceful alternatives. But drones have been both vital to our efforts abroad and brutally effective in the War on Terror.

David Freed ’16 is a Crimson sports writer and editorial comper in Wigglesworth Hall.

The Never-Ending Drone War

In his second inaugural address, President Obama declared, “We, the people, still believe that enduring security and lasting peace do not require perpetual war.” Yet the administration’s legal justification for the use of drones to kill American citizens explicitly relies on the premise that we are at war. While drones have been effective in killing leading terrorists, their use threatens to continue the United States’ commitment to war for the foreseeable future rather than helping to end the longest state of war in our nation’s history.

As laid out in a recently leaked Justice Department white paper, the administration derives the legal justification for these attacks primarily from the Authorization for Use of Military Force. This 2001 law authorizes the president to combat those responsible for the 9/11 terrorist attacks in order to prevent future attacks.

The administration defines “those responsible” as the senior members of al Qaeda or associated groups who pose an “imminent threat” to the United States by planning or participating in terrorist activities. Further, the administration claims the right to kill without evidence of a specific terrorist plot and says merely having been involved in the previous planning of terrorist activities is enough. Given al Qaeda’s widespread reach in the Middle East and Africa, what current or future terrorist group in the region would not qualify as a target? And how many leaders of these groups have never been involved in the planning of attacks against the United States? I fear the administration has effectively given itself the power to kill any American citizen high up in any terrorist group until such groups no longer exist—or until Congress repeals the AUMF.

The United States will never be able to wipe out terrorism entirely. Obama’s drone war thus calls for perpetual war.

Daniel E. Backman ’15 is a social studies concentrator in Mather House.

Drones: a Good Tool for a Tough Job

The United States’ use of combat drones is quasi-Orwellian and has become a blemish to our national image. Despite this, the use of drones is a fundamentally good policy for the United States.

Drones are the best tool we have for conducting surgical strikes in populated areas. Drones can constantly monitor an area, find the best possible moment to strike, and stay on site to monitor the results without endangering the lives of US forces.

Like any new invention, our understanding of how to best use drones is still evolving, and a critical public eye is key to ensure the proper development of drone doctrines. Public pressure has ensured that every strike is agonizingly reviewed beforehand, and as a result fewer mistakes are made every year. A drone can monitor a situation for hours before striking, making it less likely to kill innocents than traditional methods. Although these strikes will still generate anger, this is more to do with the inherently violent nature of war and not due to the nature of drones themselves. Drones have become a symbol for our wars, and therefore popular opinion about them is a reflection of opinions about our wars on the whole. From the constant surveillance required by modern warfare to the terrifying destruction wrought by a modern missile, drones embody the horror of modern warfare. Yet, Drones are the best tool our servicemen and women have to wage war. Objections against the use of these tools are misdirected—protest the war, not the drone.

Gregory C. Dunn ‘16 lives in Canaday Hall.

Read more in Opinion

Let Them PlayRecommended Articles

-

Enter the DronePaging Peter Sellers. Suddenly, it seems, a whole lot of people have learned to stop worrying and love the drone.

-

Karthinking About DronesAs more, varied, and better drones become ever more useful substitutes for riskier methods of force projection, diplomacy could lose much of its attractiveness.

-

God Bless DronesThese strikes are not only wiping out threats, but they are also preventing present insurgent forces from organizing themselves effectively.

-

Our Very Own Campaign of TerrorThe US needs to significantly reform its use of drones in the region, if not completely abolish it.

-

Assessing a Legal Framework for Drone StrikesThe U.S. needs to develop an effective balance between efficient systems of eliminating targets and respect for the constitutional rights of terrorists, whatever they may be.