I’m not the first person in the classroom, but I’m proud to say I’m not the last. I have dragged myself out of bed at 8:00 a.m. on a Friday morning, inhaled a dining hall chocolate muffin while speed-walking to the Barker Center, and by 9:01 I’m here, taking my seat in Slavic Da: Beginning Polish I.

My classmates sit silently, flipping through the textbook that I don’t have. The seminar table is a strange collection of tired-looking people, six or so, who I have never seen before. Across the table to my diagonal right is probably the only guy at Harvard with both tattoos and a nose ring.

The door swings open and the man it reveals—tall, with a gray oxford, light blue pants, and glasses—must be the instructor. He greets us with a wave that sweeps across the table, but then takes the seat next to me.

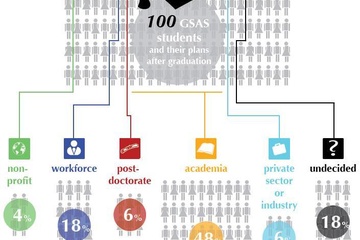

My classmates brace themselves, knowing from Wednesday’s class that he is the chatty one in their midst. “So! What does everyone study?” he asks, before answering his own question. “I’m a postdoc in English literature, and I’m teaching a few classes this semester.”

On the other side of the table, the tall guy with the middle part looks around and then speaks. “I am undeclared! I am a freshman!” he says, confirming the obvious.

The postdoc turns to me. “What about you?” he asks.

Before I know it, I’m lying. “Ummm, yeah, me too, I’m thinking about being a History and Literature concentrator,” I squeak out as quickly as possible, relieved when attention turns tothe athletic, unfriendly-looking girl on my left.

Down the table is a Human and Evolutionary Biology concentrator, wearing pearl earrings. She’s learning “survival Polish” because she does her fieldwork in Poland. “I research breast milk,” she says, nodding her head.

The real professor walks in on the hard sound of the “k.” The English postdoc calls out, “How do you say ‘breast milk’ in Polish?”

“Mleko matki is ‘mothers’ milk,’” she says.“But that is too complicated. For now, jzien dobry!”

We jzien dobry the professor back. It means good morning, always the first thing you learn.

She says it again, waits for a beat. “Powtarzaj za mną!” she says into the silence. I sit dumbly as the table begins to speak. Now I’m acquainted with my third Polish phrase. Repeat after me.

Names must be coming soon, I realize. And yes, immediately, here they are—“There is someone new here today! Jak si´ pani nazywa?” The professor looks in my direction. I look back. She asks again, “Jak si´ pani nazywa?”

The first name that comes to my mind actually belongs to my best friend from home. “Molly,” I answer finally. But this is unsatisfactory, for it cannot be said in a Polish accent. Still, the class tries their best. “Nazywa się Mo-lee!” they say enthusiastically, in unison.

After we go over names—Veronique becomes Weronika, Steven becomes Stefan—the professor hands out our sectioning cards. I can’t remember what letter to put in the “Slavic___” blank, so I peek at the English postdoc’s card. It says Da, which I copy down, but can’t help feeling like I’ve cheated.

“Now,” she says, “Lekya pierwza. Lesson one. Powtarzaj za mną!” This time I repeat. I try to crunch the consonants in my mouth, but it’s not working. It doesn’t work for the next halfhour, as I scramble to write down the vocabulary of classroom objects and the differences between masculine and feminine adjectives.

Krzesło, chair. Sala lekcyjna, classroom. Okno jest czyste, the window is clean. Stół jest duży, the table is big.

As soon as these sounds begin to make sense, it’s 9:57. Today’s class is over. “Do widzenia,” the professor tells each of us as we rise from the table. I say goodbye back, and parrot the Polish thank-yous she receives from everyone else.

At 10:01 a.m. lekya pierwza, lesson one, is over, and I’m not a freshman anymore. I head out the door and walk quickly—I have my own Friday morning language class to catch. In Persian, though, I’m Jess-eekah, and we’re starting the alphabet. Derse aval. Ba’ad az man tekrarkon. Lesson one. Repeat after me.