“His aesthetic was so intense, it almost made sense that it should burn itself out,” writer and critic Lev Grossman recently remarked in The New York Times about novelist Mark Leyner’s 14-year hiatus from the world of fiction. “I always kind of imagined Leyner having finally collapsed in on himself, becoming a neutron star or a black hole.” Much like a cosmic implosion, “The Sugar Frosted Nutsack,” Leyner’s first novel since 1998, operates on a scale incomprehensibly vast—the book opens with the creation of the universe—and incredibly small, as much of the novel focuses on the life of one strange man. Luckily, Leyner puts Grossman’s premature worries to rest: In “The Sugar Frosted Nutsack,” he crafts a hilarious combination of divine creation and mundane reality.

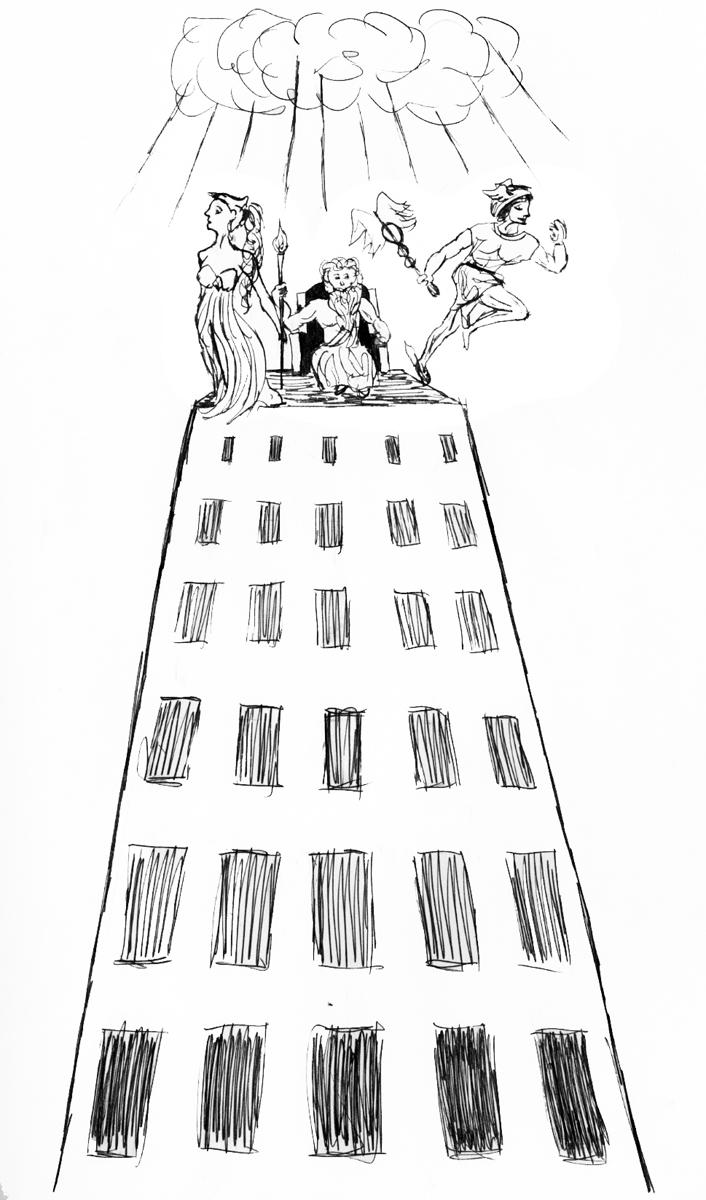

Leyner’s epicurean gods are no ordinary deities; rather, they are a 14-million-year-old shape-shifting motley crew of “drug-addled bards” that include deities such as El Brazoi, God of Urology and Pornography; El Burbuja, God of Bubbles, Dogs, New York, and Shit; Fast-Cooking Ali, God of Woman’s Ass; José Fleischman, God of Dermatology; and perhaps most importantly, XOXO, God of Head Trauma, including Concussions, Dementia, Alcoholic Blackouts, etc. The gods descend to Earth in a bus that plays a tune similar to the Mister Softee jingle and begin their eternal meddling with the lives of mortals. Once they splinter off into melodramatic factions, inter-God relations take on the tone of a soap opera that happens to affect all of humanity.

With shout-outs to popular figures as diverse as Lloyd Blankfein, Béla Bartók, Heidi Montag, Charlie Sheen, and the Marquis de Sade, “The Sugar Frosted Nutsack” is an uproarious foray into the lightest and darkest stretches of Leyner’s self-consciously wild imagination; yet despite its hilarity, it contains a surprising amount of profundity. The novel centers about the gods’ current obsession: Ike Karton, a butcher from New Jersey, whose own epic family story—also titled “The Sugar Frosted Nutsack” (T.S.F.N.)—appears in various forms throughout the novel. But Ike’s tale is at risk, for XOXO and his immortal allies are attempting to corrupt the epic as it is handed down through generations. Thanks to Leyner’s creation of XOXO, the novel hardly forms a coherent narrative—though in a work whose subject matter is already haphazardly artistic, that does not necessarily detract from quality.

Before Leyner explores the inner story of T.S.F.N. he inspects the seeming irreconcilability of brilliant and dull godly creations. After describing the most noteworthy accomplishments of each god, he writes, “What does this wild oscillation between the sublime (e.g. the creation of musical harmony, the electromagnetic spectrum, prime numbers, the Riemann Zeta Function, etc.) and the gratuitously sadistic (e.g. giving someone a grotesquely disfiguring facial tumor) reveal to us about the Gods?” Leyner’s humor explores the oft-questioned disparity between the beautiful and the damned from a new and poignant perspective; rather than one god who creates good and evil from infinite chaos, the sharp comparisons around the world instead reflect the whims and fancies of a troop of hedonistic deities.

In a mess of lusty gods and sex-crazed humanity, the narrative of Ike’s family story is not always easy to identify. The labyrinthine nature of the tale is a result of XOXO’s devious subterfuge. “An infinitely recursive epic that subtends and engulfs everything about it (i.e. everything extrinsic to it), and that has…been subject to the impish and sometimes spiteful corruptions…of XOXO,” Leyner writes, “presents a phenomenon that’s difficult to get your mind around.” Self-aware statements like this one, which occur throughout the book and ostensibly reference both the novel itself and the story within a story, begin to imply that both sagas gain meaning not through content, but through the experience of reading. Leyner seems to encourage the reader not to give up, to look beyond the immediate confusion of the novel and to seek its deeper meaning.

The story of T.S.F.N. is cast as an epic that is inherited through oral tradition. Its playful references to mythical stories and the culture that surrounds them ends up creating, through a peculiar combination of admiration and ridicule, a larger-than-life quality for the novel itself. The most facetious of Leyner’s flirtation with historical epics is his allusions not to Greek mythology, but to James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” Leyner first ironically addresses the content of “Ulysses” with Ike’s opening monologue on his hankering for a meaty breakfast, much like Leopold Bloom’s opening musings. Later, Leyner comments on the cultish culture surrounding “Ulysses”—including Bloomsday festivals and yearly pilgrimages to Dublin that reanimate the events of Joyce’s novel—when CALLER asks REAL HUSBAND on the reality TV show The Sugar Frosted Nutsack where Ike’s first butcher shop is located, because he plans on visiting all the key sites in Ike’s life over the course of one weekend. In many ways, Leyner mocks epics by attempting to create one, from the set-up of gods meddling with mortals to references to specific epics like Ulysses.

The novel is mostly fun and entertaining; it may be easy, however, to tire of the incessant glare of culture references and grandiloquent literary gestures in the novel. Even David Foster Wallace once lambasted Leyner’s overblown desire to entertain his readers by arguing, in his essay “E Unibus Plurum: Television and U.S. Fiction,” that Leyner’s writing was “less a novel than a piece of witty, erudite, extremely high-quality prose television” that ends up ringing “oddly hollow.” But such a claim seems hardly relevant in Leyner’s latest effort, which, despite its outrageous humor, traces a vein of contemporary culture too bleakly authentic to remain void of consequence.

In fact, Wallace’s criticism highlights Leyner’s greatest accomplishment in the novel: his ability to keep the massive force of his absurd writing contained within a relatively sincere framework. At one point in the novel, a fictional Alan Greenspan concludes that T.S.F.N. has never really been about Ike Karton, but rather “about the war between XOXO and the epic itself, i.e., the war between the boldfaced and the italicized”—that is, the war between frothy punch writing and its meaningful undertone. With its impressively small radius of action and high density of characters, “The Sugar Frosted Nutsack” is indeed a black hole that sucks its reader into an endlessly entertaining world replete with boldface comedy and italicized gravity.

Read more in Arts

Mother-Daughter Maelstrom in Bechdel’s Latest Memoir