“Divide and conquer is sort of the design scheme here,” says antiques dealer Andrew Spindler as we walk toward the concrete and brick rectangles of freshman dorm Canaday Hall. “I got solitary confinement,” says Spindler’s friend and interior designer Heidi M. Pribell ’82, a former Canaday resident.

Built in 1974, Canaday was constructed to prevent student riots: “They didn’t really want you to assemble,” says Spindler. In this sense, Canaday is an obvious example of an interior designer’s ability to influence behavior. Another aspect of freshman dorm design also caught Spindler’s expert eye: a lone teddy bear perched on a Thayer windowsill. “There’s some context where stuffed animals in the window mean you’re a drug addict,” he explains.

Surrounded by students in bright shorts ranting maniacally about “Love Story,” I wandered around campus chatting with Spindler and Pribell about the relationship between building design, history, and function. The autumnal ritual of nervous, curious, and bemused freshmen moving into the 17 redbrick first-year dorms has been repeated once more, debt ceilings and Arab revolutions be damned. This is where they will sleep, eat Annenburgled food, study, relax, and drink soda during the year to come. While they may have agonized over which Urban Outfitters notepad would best suit their desk, hardly any freshmen think of how the design of these dorms will affect their behavior. And though design is usually understood in terms of aesthetics, it can also be discussed in terms of social effect. Enter Spindler and Pribell, experts recruited to tour the freshman dorms and analyze this potential influence.

DESIGNING DECORUM

Design Critic and Graduate School of Design Lecturer Gabriel N. Duarte leads me through the Graduate School of Design’s Gund Hall, an angular, symmetric interior of concrete, glass, and metal. We pull together two chairs in a meeting room, thereby creating a private office. For Duarte, design encourages rather than limits certain modes of behavior. “So many people think that architecture is supposed to prevent you from doing stuff. A window is so that you don’t jump out of your bedroom. A door is to be shut,” he says. Design, then, provides a range of suggestions for how people can act in a given space. Though it may not condition behavior, it does provide behavior’s vocabulary.

When design attempts to be inoffensive, it provides an unduly limited vocabulary. “It’s a commonplace thing nowadays that if you have these super bland and flexible spaces people actually don’t use them to their full extent because they’re not stimulated to think about what that space can be,” Duarte explains. In a dormitory, where the design seeks to be universally tolerable, ‘bland and flexible’ are aspirations more than criticisms. Great design, however, does not necessarily ensure creative and productive behavior. “People can be stimulated to do [something], but not be told to,” says Duarte. “There’s a difference.”

Duarte’s point is that design goes beyond aesthetic: a room is no more four walls than a smartphone is a jumble of plastic and metal. “When you design something like [a smartphone], you’re not just designing the object, but you’re designing the set of relationships that the object allows you to have with other things,” he says. In this way, a designer does not simply create a room design but actually influences the inhabitant’s relationships with the things and people in that room. While bad design leaves a space anonymous and inactive, good design opens up possibilities for interaction and activity. Duarte points to our ‘office’ for emphasis. “Like this chair. A chair is a chair, but once they’re placed like this they just become like a living room.”

CANASTROPHE

“The chair definitely anticipates that you’re going to be rocking back and be a nervous wreck. They probably have had experience where the chairs kept breaking,” says Spindler as we examine the standard-issue Harvard desk chair. We’re inside Canaday, now, and after being greeted by what Spindler deems a “claustrophobic” hallway, exploring the bathrooms, and passing some unsuspecting entryway-mates, the designers are poking around the common room of Lucy A. Walsh ’15.

The two make their way to the suite wall, where a fire extinguisher sits. “Like the size of this,” says Spindler, pointing to multiple warning signs, “this doesn’t need to be that big … this is like when you get a Skymall Magazine and all of the products are all in anticipation of some kind of apocalyptic event.” “It just should say ‘hazard, hazard, hazard!’” chimes in Pribell, flashing her hands with each repetition. “This is like when you go to a restaurant and order a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, and they have a sign saying that there may be peanuts in it.”

While both designers were generally critical of Canaday’s isolating layout, they agreed that its location—situated close to classes and with striking views of both Memorial Hall and Memorial Church—was, in Spindler’s words, “primo real estate.” “I think that when you come to Harvard as a freshman, you really want to look at ivy-covered walls,” he suggests. “[Canaday] really fulfills the fantasy of ivy-covered walls.” When I ask Spindler what kinds of freshmen he would put in Canaday, he replies, “People that need to be disciplined and sequestered. Or ascetic types who thrive on serene views of campus with a minimal amount of interaction.”

We continue into Walsh’s bedroom, a medium-sized single with standard Harvard furniture: a desk, bookshelf, bed, and drawers. “The big expression of any individual is the bedding,” says Pribell. “I mean, I got in trouble my freshman week because my mother told me I couldn’t get my own bedding, that I’d have to use Harvard bedding. I cried so hard.”

PIPE-WORTHY

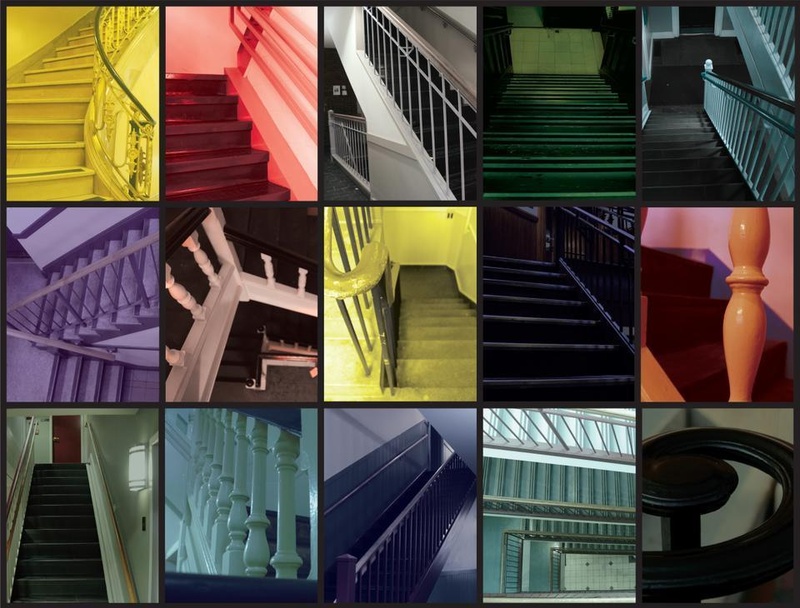

“This is definitely [in the style of a] gentleman’s club,” says Spindler as we enter Matthews Hall, built in 1871. He points out the surrounding dark greens, elegant wainscoting, and gothic-inspired ironwork. “People should be smoking pipes in here,” Pribell adds with an awed voice. We climb the open staircase and the designers rush through quickly, stepping out of their way to get a closer view and to touch the walls and wood.

We invite ourselves into another room, and Spindler and Pribell are immediately taken with the surroundings. I ask them if this space—a larger, well lit common room, wood floors and paneling, and a large window seat—encourages anything that Canaday prohibits. “Assembly,” says Pribell, almost immediately. “I think that it is definitely more communal,” embellishes Spindler. “I think it’s snuggly!” interrupts Pribell.

We finish looking around and leave Matthews for a last stroll. As we walk away, Spindler and Pribell agree that the dorm is elegant, almost to the point of excess. “This was a bit of a vanity project for Mr. Matthews, don’t you think?” he asks. “Yeah,” she replies, “everyone’s searching for immortality.”

We exit Matthews and talk furniture on the way to Apley Court. “A desk can tell you so much about the social history and cultural history in the time in which it was made. Issues of privacy, correspondence, power, I think all those things you can find,” says Spindler, as he discusses his profession as an antiques dealer. He points to the history in our quotidian possessions, their ability to tell a story, how they were used, how they were intended.

Apley, the 1897 brownstone apartment complex just south of the Yard, was originally intended for the wealthy, male students of a bygone era. The room we visited, however, was inhabited by two female students, proudly on financial aid. Spindler calls attention to these students as evincing democratic change: these spaces were designed for an utterly different type of individual who would bear no resemblance to today’s residents. “I think today, the stereotype of who would live here, you know, the Winklevoss twins, I think they’re in a way archaic as far as the typical profile of Harvard students.” In Apley, the contrast between design intent and building use shows that a building’s designer may not be able to control actual behavior even while her goals remain clear.

SHAPE THE SPACE

In each dorm that we visited, Spindler and Pribell identified subtle aspects that create a consistent, even overwhelming aesthetic. In Canaday, the design dynamic of power and control the dorm manifests itself today in modern isolation; in Matthews, the elegance becomes an encouragement for enthusiasm and socializing; and in Apley, the grandeur becomes a reminder of the patriarchy and elitism of the past. “[College students] should be aware…[that] they have to occupy [a space] to make it useful. There’s a saying in architecture that space only exists once it’s actually performed. Otherwise it’s just a place.” No matter the strength of suggestion, in the end it is the students who decide which hints to pick up on.

—Staff writer Keerthi Reddy can be reached at kreddy@college.harvard.edu.

Read more in Arts

Stephen Malkmus Continues to Slack Off