To win over a conservative Senator from Tennessee, it helps to know the South—as University President Drew G. Faust can attest.

During a meeting earlier this year with Senator Lamar Alexander, a Tennessee Republican, Faust sat down across a table from a man who partly controls funding for Harvard’s largest sources of federal dollars at a time when the Republican party is seeking to make deep cuts in the federal budget.

But Faust managed to win over Alexander, taking one step toward assuring that Harvard would not face a major shortfall in funding.

Faust, who is descended from a long line of Tennesseans on her mother’s side, seized on the memorabilia from the state in Alexander’s office, finding common ground with the Senator in their shared roots.

Then she got down to business pitching higher education to the Senator.

Several times this year Faust has trekked down to Washington D.C., put on a smile, and made her case for Harvard.

After the financial crisis dealt heavy blows to both the University’s endowment and to the federal budget, Harvard is in a tight budgetary spot as it scrambles to continue funding ambitious science research and recruiting the most talented students.

Harvard receives roughly $600 million per year, largely in the form of grants, from the federal government. Counting the teaching hospitals, the total comes to around $1.2 billion annually. But now this source of funding is in peril as Congress is set to sharply cut spending for the coming fiscal year.

“Her concerns are not unfounded,” said Senator Richard J. Durbin, an Illinois Democrat and the assistant Senate majority leader, who has met with Faust in D.C. to discuss science funding and other legislation.

These challenging circumstances have forced university presidents to get their hands dirty in Washington politics, as they advocate for continued funding of research and student financial aid.

On these front lines, Faust is leading the way.

“In this budget environment you have no choice,” said Vice President for Public Affairs and Communications Christine M. Heenan, “but to make your case early and often.”

According to historian and lecturer Stephen P. Shoemaker, Faust is the most politically active president in Harvard’s history since James Bryant Conant, Class of 1914, helped spearhead the Manhattan Project.

The magnitude of the current stakes in Washington has left Faust with no choice but to roll up her sleeves and wade into federal politics. “I try to be a face for Harvard that makes it seem an important part of the nation’s future,” she said. “I need to make that case. All of higher education needs to make that case.”

THE STRATEGY

When Faust goes to Washington, she brings a carefully crafted strategy, a bevy of data, and stories about the good work being carried out in Cambridge, all tied neatly together with a dose of charm.

Heenan said that universities must determine “how to best deploy their president as an asset toward their advocacy agenda,” evoking the language of battle and apparently emphasizing what is at stake for Harvard in Washington.

This means employing Faust’s clout and political capital selectively to make headway with important lawmakers.

“I am more likely to get direct access to the principals and to be able make the case for higher education to people in the Senate and House of Representatives,” Faust said of her choice to travel to D.C. in certain instances, rather than send other University affiliates.

Harvard uses a two-pronged strategy, filling Faust’s itinerary with both lawmakers and journalists in the capital.

Faust has met with political bigwigs including President Obama, Vice President Biden, and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, as well as journalists and other Washington insiders. During her trips to the capital her schedule also includes op-ed columnists, think-tanks, editorial boards, and other opinion makers.

This past year, Faust participated in a reporter roundtable, a type of off-the-record schmoozing used to give journalists insight into the challenges facing a university in a candid forum.

“I think this is a somewhat unique approach at Harvard to reach both lawmakers and those who seek to influence them,” Heenan said.

Though Faust’s team said that she attempts to make connections across the political spectrum, her efforts this year have been weighted toward Democrats, who by and large tend to be in favor of funding for Universities. Out of at least 17 meetings with politicians or government leaders in Washington this year, only 4 were with Republicans.

However, with the Republicans having recently taken over the House, University administrators are quick to emphasize that an effective lobbying strategy has to cross the political divide and reach out to GOP lawmakers.

“It would be a very dangerous thing if science became a partisan issue,” Heenan said.

When meeting with members of Congress, Faust comes armed with facts and figures about the cutting-edge cancer research conducted in Harvard laboratories. She also touts the student body’s diversity and the number of students who currently graduate without debt.

But as much as politics is about coming armed with the right data and a good argument, it also requires a bit of wit and charisma. Faust has found herself in unfamiliar territory on Capitol Hill, but it appears that she has embraced the role of winning over lawmakers with gusto.

Harvard and other elite universities are often criticized by conservative Washington politicians for being out of touch with the country’s mainstream. Therefore when lobbying Congress, Faust has had to grapple with what is perceived as a peculiarly Harvardian brand of elitism.

“I think universities are right now very much misunderstood,” University Provost Steven E. Hyman said. “A place like Harvard is mistakenly caricatured as an elitist bastion of peculiar beliefs.”

But with ties to the American South and a knack for recognizing shared roots, Faust has grown more adept at winning the hearts and votes of both liberals and conservatives.

Earlier this year, Faust met with House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, a darling of the far right and an influential Republican. Cantor represents a wing of the Republican party that is largely opposed to the initiatives being promoted by Harvard in Washington—stem cell research, for example—but in their home state of Virginia, the two found a shared love.

Before he left the meeting, Cantor told Faust that she needed to travel to Washington more frequently to ensconce herself as the face of Harvard and dismantle the image of the old, white Harvard man in tweed.

“It’s always important to try to make a personal connection with someone and treat someone like an individual person and not come in and act as if they’re just a vote,” Faust said.

As a president that lacks the strong Washington ties of her predecessor Lawrence H. Summers, who was Secretary of the Treasury before assuming the Harvard presidency, Faust has had to make up ground to establish herself as a presence in the nation’s capital.

“Before I ever met her she seemed like an imposing woman. A great scholar,” said Executive Washington Editor for Bloomberg News Al R. Hunt, who hosted the reporter’s roundtable. “The one thing that we’ve benefited from is seeing what an interesting and down-to-earth person she is.”

WADING INTO WASHINGTON POLITICS

The Office of Government, Community, and Public Affairs was founded in 1970s during President Derek C. Bok’s tenure, although it went by a different name at the time, according to Casey, who has been in involved in Harvard’s lobbying efforts for 20 years.

“Derek was very farsighted, and I am sure he could see the growing importance of the federal government to the University,” said Nan F. Nixon, who was one of Harvard’s first chief lobbyists.

The need for a University lobbying office goes back to the historic expansion of the federal government that followed World War II with the passage of the GI Bill and the creation of Pell Grants. These acts funneled money from Washington D.C. to U.S. universities, encouraging Harvard and others to jockey for position at the Congressional cash spigot.

But at the outset of Harvard’s lobbying activities, it was a far cry from the its current sophisticated effort. When Nixon was first hired she worked out of her apartment in D.C. and commuted to Cambridge each week. Eventually Nixon opened the doors at the University’s first Washington, D.C. office and added an assistant to her team.

Harvard was one of the very first universities to open a D.C. office, though many other schools soon followed suit, Casey said. MIT, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Chicago, and many other schools have all established a lobbying presence in D.C. In fact, the University of Michigan’s office is only a few floors up from Harvard’s.

Former MIT President Charles M. Vest—who is widely considered to have set the standard for university presidents’ active involvement in D.C.—said that he often encouraged other universities to focus the importance of funding for higher education and “not specifically on their universities.”

Many other schools, including Boston University and Tufts, hire lobbying firms to do most of the heavy-lifting in government relations. Harvard, however, maintains an internal team of lobbyists and only employs lobbying firms on occasion to work on specific issues, Casey said.

By having lobbyists who can call themselves a part of the Harvard community, administrators say that the University is better represented, allowing them to foster closer ties with lawmakers at the state and the federal level.

“The voices that represent Harvard are actually a part of Harvard,” Casey said.

During fiscal year 2009, Harvard reported that it lobbied on a variety of issues, including legislation affecting intellectual property law, legislation funding stem cell research and therapeutic cloning, appropriations for student financial aid, and science funding from organizations such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Earlier this year Harvard also lobbied for the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, Perkins Loans, and tuition tax credits, among other issues.

In fiscal year 2009, the University spent a total $465,946 on lobbying activities. This represents a modest decrease from previous years during which the University spent $578,480 in fiscal year 2008, and $697,700 in 2007. Casey said he believes fluctuations in spending were a function of heightened political activity during those years rather than University budget reductions.

In fiscal year 2009, $238,696—over half of the total spending—was used for “direct contact with legislators, their staff, government officials, or a legislative body,” which include Faust’s visits with politicians in Washington but not her contact with journalists, business leaders, or other Washington heavyweights.

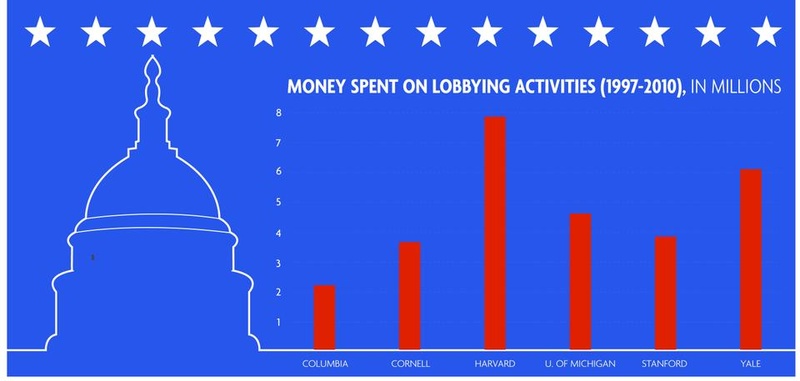

According to the Sunlight Foundation, a government watchdog group, Harvard has spent a total of $7.8 million on lobbying from 1997-2010.

Among its peers, Harvard is one of the biggest spenders on lobbying activity. During the same time period, Yale spent a little over $6 million, Stanford spent $3.9 million, and Columbia spent $2.2 million on lobbying activities.

Those dollars pay for a big presence—but they cannot buy everything.

PROMOTING THE DREAM

After Eric Balderas ’13 tried to board a plane in San Antonio using a Mexican consular card and his Harvard ID, he was detained by the authorities as an undocumented immigrant—and with his arrest Harvard became a player on the frontlines of the debate over whether undocumented youth like Balderas should be granted a path to citizenship.

The University adopted Balderas’ case as its own as a Harvard Law School professor agreed to represent him and Faust held him up to Congressmen as an example of why such students ought to be granted the opportunity to gain citizenship.

Faust led the charge among university presidents to advocate for the DREAM Act—one example of the way that she has pushed for a more activist role in Washington. Though immigrant rights activists mounted a major campaign to push the law through the Senate, it would stall after failing to garner sufficient conservative support.

But when Faust travels to Washington to advocate on behalf of a specific piece of legislation it also raises questions about when it is appropriate to put the Harvard imprimatur on certain policies, an issue that was particularly present in lobbying for the DREAM Act.

Some argued that lobbying for the DREAM Act overstepped the role of the president because it benefitted a group not directly tied to Harvard—but rather a limited population of potential Harvard students—and because it was a highly partisan issue backed heavily by Democrats.

But Durbin, who authored the DREAM Act and met with Faust on the issue, said he believes her endorsement is an important step in garnering broad support for the legislation.

In discussing her support of the DREAM Act, Faust often likes to tell the story of meeting with a group of undocumented students at the College, an experience that she has said convinced her of the urgent need to act on immigration reform legislation.

“I would draw the lines of appropriate engagement as issues having a direct impact on the University or its students in a way that inhibits them from fulfilling their educational goals, so that’s why I chose to speak on the DREAM Act,” Faust said.

But in these issues, Faust also has to consider Harvard’s position among its peers. When Harvard moves, other Colleges tend to follow, and that was apparent in Faust’s advocacy in support of the DREAM Act.

Heenan—who noted that several other university presidents followed Faust’s lead in backing the DREAM Act—said that as president of Harvard, Faust understands how she can use the bully pulpit to refocus public attention on the importance education.

“I think she is quite conscious in every setting of the fact that there will always be some that look to Harvard to set the standard and define the agenda,” Heenan said,

—Staff writer Tara W. Merrigan can be reached at tmerrigan@college.harvard.edu.

—Staff writer Zoe A. Y. Weinberg can be reached at zoe.weinberg@college.harvard.edu.

Read more in News

Serving the Community?