Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Ilisa Barbash originally planned to make a movie about rural environmentalism, but after three summers in the Montana mountains and over 200 hours of footage, they ended up with one about sheep. In “Sweetgrass,” the husband and wife duo, Visual and Environmental Studies and Anthropology Professor and Associate Curator of Visual Anthropology at the Peabody Museum, respectively, follow hired hands as they bring sheep across the dangerous Absaroka-Beartooth Mountains to graze for the last time.

The result is a both gritty and lyrical. “We never called this film a documentary,” says Castaing-Taylor. “We were filming the last time they would graze in those mountains. But we were also wondering, ‘How could this still be happening in the 21st century United States?’”

“Sweetgrass” opens on April 2nd at the Kendall Square Cinema.

The Harvard Crimson: How did you get the idea for “Sweetgrass?”

Ilisa Barbash: When we were professors the University at Boulder, we got an email from friends at NYU who knew someone who was leasing land to the rancher in the film. He had told them, “I am the last guy to ranch like this, and someone should make a film about me.” He would be the last rancher to ranch in the Absaroka-Beartooth Mountains for the summer. The email asked if we had students who might be interested in doing the movie. We said, “No, we’ll do it.”

THC: Why was this going to be his last time?

IB: Because it is hard to do. Two people up there watching sheep—it’s emotionally grueling.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor: Sheep-herders often blame environmentalists for changing patterns for the demand for sheep. But it’s really brute economics. During WWII there was a surge in demand for lamb and wool. That demand dwindled, and there were too many sheep in the states. Since, Americans have been eating less and less lamb. And they wear wool less and less too.

THC: I didn’t explicitly get those facts from the movie. Why did you choose not to give any background information or even narrate the film?

IB: We really wanted people to look at the film and to have a kind of transportive cinematic experience. We didn’t want people sitting in the audience watching journalism. That’s why we held the title card that tells you this is the last time this will happen until the end—so that you are not thinking about it throughout.

LCT: We didn’t want the audience viewing it throughout as a rose-tinted nostalgic spectacle.

IB: I think that there are plenty of spoon-feeding documentaries available. You don’t need to go to a theater to see something like that. This way was more interesting than conveying expository information.

LCT: Well, we don’t live life privy to all the expository information that we might wish to have. When we see fiction, we are not given that information either. Fiction films simulate life as it’s lived through acting and plot. Documentary claims not to be fiction and to therefore privilege human existence. The paradox is, it almost entirely consists of people after the fact telling you about their lives. If you asked me about my life, I would just lie through my teeth. Our aesthetic aspiration was about ambiguity, not about clarity. We didn’t want to give people the sense of reducing the magnitude of people’s lives to an issue.

THC: You talked about the aesthetics of your movie—what kind of film were you filming on?

LCT: It was shot on digital video, not film and not an HD digital camera. My students wouldn’t touch our equipment today—it’s outdated—but it was the best camera we could afford then. I carried the camera on a harness—a big body bracer. That way I could hold the camera at knee level and move with it.

For the sound, we would put small microphones on people, occasionally on the sheep or the horse or the dog. Not so much on the animals—[the microphones] were very expensive and the horse would often break it and so on. That way, while I was filming, I was also listening to people who were a mile and a half away from me

IB: And then we blew up the video to 35mm film.

THC: Walking behind the sheep must have been quite an experience—I imagine that many sheep produce quite a bit of waste.

LCT: Yes. There’s a shot where the sheep go through a town. The municipal authorities had just cleaned the street. 3000 sheep went through and it was just covered with sheep shit afterwards.

THC: You have talked about your film’s relation to ethnography—isn’t filming “the last” of something a common trope in ethnographic films?

LCT: It’s a completely embarrassing cliché. It’s been critically embarrassing for the last 30 years.

IB: It has its roots in the basics of anthropology. Margaret Mead’s “Principles of Visual Anthropology” called for people to go and document disappearing cultures.

LCT: It is often though, that privileged Western observers lament disappearing cultures when they are usually in ways quite oblivious and somehow complicit in the cultural tendencies. For that reason, it has lost any kind of credibility. That is a reason we were interested in it. And although this ended up being the last herd ranched in this way, we also wondered how this could be happening in the 21st century United States.

THC: What did the sheep-herders think of your project?

LCT: They didn’t need any convincing—the ranch owners had invited us to film. There wasn’t any reticence to our presence, but some wariness. The two hired hands [who are much of the film’s focus]—I am good friends with them both.

In many parts of the world there’s a different imagination at work about the environment. The notion of wilderness as space out side realm of human agency is peculiar to America. It’s almost an arrogant conception of nature—it implies we are not natural, just purely cultural. In Europe, there is more of a continuum, a spectrum of human culture and animal-nature relationships. It’s more subtle than either or.

—Madeleine M. Schwartz

Read more in Arts

Barenaked LadiesRecommended Articles

-

Ruling Rugby

Ruling Rugby -

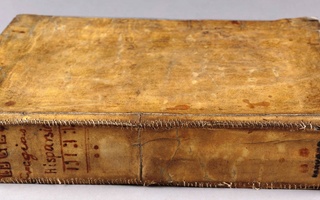

The Real Skinny: Harvard Books Not Bound in Human Flesh

The Real Skinny: Harvard Books Not Bound in Human Flesh -

5Q: William Deresiewicz

5Q: William Deresiewicz -

The Sheep and the Fat OxIf no one challenges “common wisdom,” how can we discover the error of our ways? It was sheepdom that caused Aristotle’s assertion that heavier objects fall faster to remain unchallenged for almost two thousand years, until Galileo decided to check it.