Alexis de Tocqueville is famously taught in American middle schools and high schools as the Frenchman who loved America and who wrote the treatise “Democracy in America” in the mid-19th century. There is usually no further discussion of the man or his famous book before moving on to material deemed more important by state-standardized testing boards. The motives behind Tocqueville’s mission are therefore overlooked and any meaninful insight into his character is completely lost.

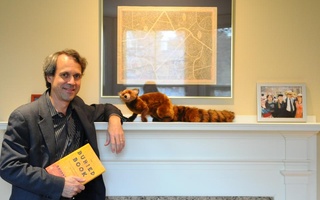

Tocqueville once wrote, in reference to the danger of America’s non-authoritarian, self-governing society, “Once an idea has taken hold of the American people’s minds, whether it’s a just one or an unreasonable one, nothing is more difficult than to uproot it.” One could say Harvard Professor Leo Damrosch faces this challenge in writing “Toqueville’s Discovery of America.” In his new book, Damrosch is attempting to remedy the general American conception of Tocqueville through a meticulously-researched, accessible, and thoroughly charming account of the writer’s journey across 19th-century America. Instead of leaving Tocqueville as the flat character oft-quoted in college government and history classes, Damrosch delves into letters, journals, and accounts—many published for the first time in English—to fill in the missing dimensions of the political thinker’s life and experience in America.

“Tocqueville’s Discovery of America” reads more like a novel than a deeply-investigated historical text. Damrosch weaves insights pieced together from his extensive research with many of Tocqueville’s own words and those of his companion, Gustave de Beaumont, to construct a biography of Tocqueville. Scattered throughout the text are illustrations of Tocqueville, the people he met, and the scenery he witnessed on his journey, contributing to the authentic, accessible feel of the book. In addition, the intimate details of Tocqueville’s life—from his loss of faith to his sexual adventures—add color, humor, and warmth to the image of the social scientist.

Damrosch’s purpose in “Tocqueville’s Discovery of America,” however, is not solely to demystify the man behind the famous work of social science. The anecdotes about Tocqueville serve a greater purpose: to illuminate the ideas and thought processes of an author who wrote the text that continues to define American democracy across the world.

One of the most striking chapters is “Boston: Democracy as a State of Mind,” in which Damrosch recounts Tocqueville’s run-ins with Boston bluebloods and intellectuals, who were more like French aristocrats than any Americans that he had met up to that point. Between his discussions with intellectuals and civilians that he met on the streets, Tocqueville became aware of the distinct separation between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law in America. He concluded that the “habits of the heart” and the ideals of the common people held together a society as much as written laws.

He also came to understand the different methods of centralization that caused such a huge difference between French and American societies. The astounding French bureaucracy and central decision-making process in Paris meant that French communes “vegetated in invincible apathy.” By contrast, Tocqueville saw that the American system of umbrella federal governance with state and local administration and enforcement allowed citizens to come up with and execute innovative new ideas via “local initiative.” As Josiah Quincy, then President of Harvard and previously Mayor of Boston, informed Tocqueville, the lack of overbearing central authority in America and the abundance of “individual enterprises [surpassed] by far what any administration could undertake.”

Damrosch also highlights some of Tocqueville’s less well-known views. By exploring Tocqueville’s experiences in Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, and many other Southern states, Damrosch addresses Tocqueville’s reservations about the treatment of race in the United States. Tocqueville was vehemently against the enslavement of blacks and the poor treatment of Native Americans, and concluded in an incredibly prescient manner that the discrimination against blacks in America would result in “the most horrible of all civil wars, and perhaps the destruction of one of the two races.”

Despite the easy accessibility of “Tocqueville’s Discovery of America” and its colorful anecdotes, the book does tend to run on the dry side from time to time. “Democracy in America” is a monumental text in and of itself, and while an in-depth account of Tocqueville and Beaumont’s journey across America lends a sense of time and place to such an important work, it drags a bit when it strays from its focus on illuminating Tocqueville’s most famous book.

Regardless, Damrosch’s work lends insight into the mind of the man who defined America for the world. In “Tocqueville’s Discovery of America,” Damrosch explains the diverse experiences that allowed Tocqueville to both construct and critique America’s political ideology and the pulse of its society. As Tocqueville himself once said, “Everything I see, everything I hear, everything I still see from far away, forms a confused mass in my mind that I may never have the time or ability to disentangle. It would be an enormous labor to present a tableau of a society as vast and un-homogenous as this one.” Damrosch’s careful labor in recreating Tocqueville’s journey is not unlike his subject’s work in dissecting the vast and varied American culture.

Read more in Arts

David Mamet’s Overstated ‘Theatre’