Incest, masturbation, constipation, and the letter “C” are the main subjects at hand in Tom McCarthy’s latest novel, “C.” The author of “Remainder,” McCarthy was effectively crowned modern literature’s new poster boy when Zadie Smith wrote in the New York Review of Books that his work was “one of the great English novels of the last ten years” in November of 2008. Sadly, “C” fails to live up to this reputation on several grounds, even though it makes a sincere effort to be a literary masterpiece.

All the significant elements in the novel begin with the letter “C.” The main character, whose last name is Carrefax, goes to Cairo, does cocaine, drinks champagne, all under the supervision of a Mr. Clair. This literary gimmick provides one of the unifying elements of the book. However, there is no clear explanation for its use. McCarthy’s constant word play and overuse of literary devices becomes tedious, overshadowing the plot and the development of his characters.

Although there are certain eye-catching episodes, the plot as a whole is overcrowded and convoluted. Serge Carrefax is born to a deaf mother and an eccentric father who runs a nontraditional school for deaf children. Serge and his older sister Sophie develop a dangerously close relationship as they find their interests—radio for Serge and natural science for Sophie, all before the backdrop of turn-of-the-century Britain. Following a catastrophe, Serge’s body develops a blockage which can apparently only be cured by the loss of his virginity combined with a dose of poison berry wine, in Germany no less. He goes off to war and becomes a pilot—a portion of the novel in which McCarthy shows off his significant knowledge about World War I. On one hand this demonstration of expertise shows the author’s dedication to research and historical accuracy, but on the other it makes the writing a bit clunky and too technical for readers unfamiliar with the subject matter.

There are passages which flow quite well—Serge’s views of the landscape from his aircraft while he is on cocaine or heroin—are almost poetic, and the descriptions of his highs are some of the most compelling portions of the novel: “The diacetylmorphine takes hold as he glides back up the path and over to his RE8, turning the machines’ manoeuvres as they taxi, pause and pirouette, escorting one another into position, into ballroom-dance steps, the roar of their engines into symphonies whose every chord is laden with insulation...” But many of the other episodes are too hectic to achieve this kind of eloquence. McCarthy’s work is full of turbulent, disordered passages which are missing the careful crafting necessary to achieve the kind of literary chaos he seems to be working towards.

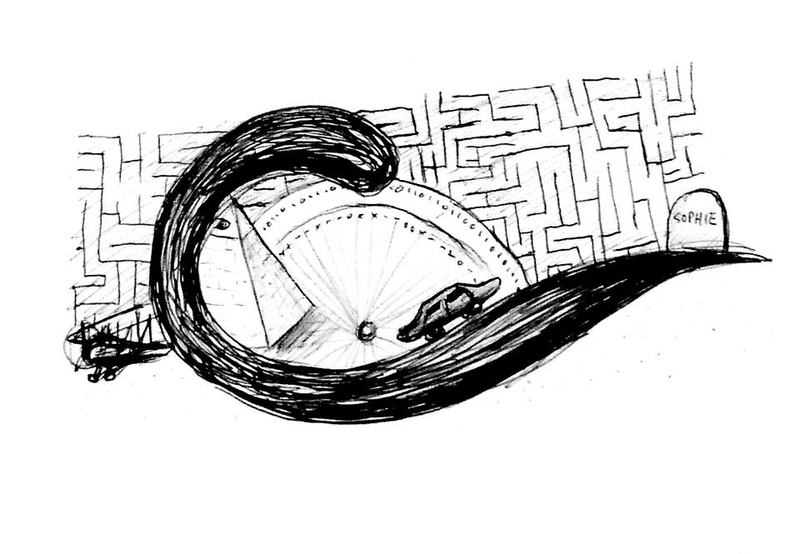

The dichotomy between chaos and clarity is central to the work. Serge, with his drug use, seems to be looking for a heightened vision of the world. He reaches occasional moments of greater understanding; at one point, a taste of bootlegged wine gives him the clarity he desires: “Serge opens his eyes now, and finds that the gauzy crêpe that’s furred his vision for so long is gone—completely gone, like a burst bubble or disintegrate membrane.” Most of the time, however, the results of his substance abuse are perilous to his health, even ending in a plane crash at one point . His search to augment his vision nevertheless continues; even when he studies visual art, his greatest struggle is to accurately render perspective.

McCarthy has a parallel difficulty creating perspective in his writing, which lacks depth and continuity. Though the novel is full of recurring images and symbols, they do not create a deeper understanding of McCarthy’s central character. Serge’s story is presented not as a narrative, but as a series of brief vignettes from the life of a remarkable, though flat young man. Though Serge is both troubled and leads a fascinating life, his character is underdeveloped and unrelatable. McCarthy’s presentation of Serge’s thoughts and passions are occasionally distasteful, but even then not enough to inspire a strong reaction.

It seems to be in attempt to get such a reaction that McCarthy riddles “C” with scatological references, off-color words, and sex. As with the constant use of the letter “C,” McCarthy’s priority seems to be on the effect, rather than the substance, of his writing. Though Serge’s story has the potential to be compelling, it is ultimately overwhelmed by McCarthy’s overworked text. Gold star to him who enumerates all of the “c’s”.

Read more in Arts

World Music Gives Cultural Studies a Voice