This school year has been one of great transition for Harvard. While the University saw the beginning of a new era with the installation of President Drew G. Faust, the College has undergone a radical change in admissions policy, a huge expansion of financial aid, and a revamped curriculum. While The Crimson was generally optimistic about the College’s new programs, we turned a critical eye to their implementation, as well as to inept bureaucratic attempts to tamper with existing structures.

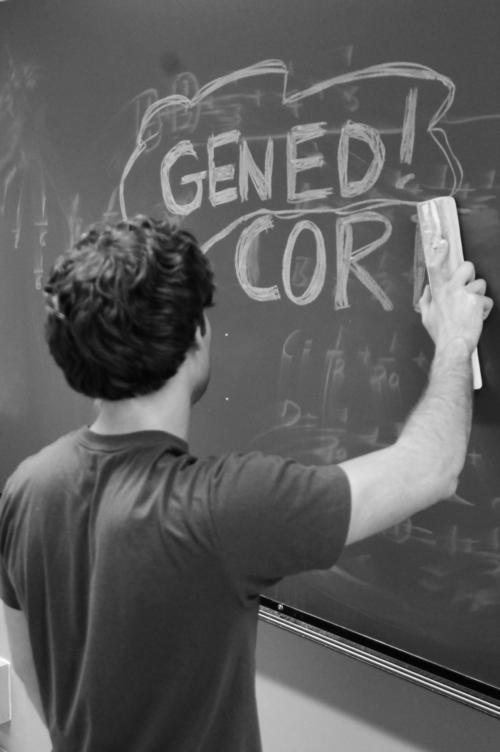

Most disappointing has been the new General Education program (Gen Ed), which has little to show after five years of debate. Although a preliminary report released a year and a half ago contained inspiring promises of engaged intellectualism and global citizenship, Gen Ed has since then devolved into an insipid mash-up of compromises that is essentially a redux of the old Core. A scant 37 Gen Ed courses have been approved for the 2008-2009 academic year, and only seven more for the following fall. Despite being set to supplant the long-criticized Core curriculum by 2009, a mere 60 proposals have even been submitted, many of which are nothing more than adapted Core courses. Meanwhile, continuing efforts to get professors to adapt their courses to the dying Core system have proven to be largely inadequate.

With both programs failing, students are caught between Scylla and Charybdis. Granting incoming freshmen a choice between the lame-duck Core and the skeletal Gen Ed will create even more confusion for students and their academic advisers, who are mostly in the dark about the process. The faculty’s own inability to articulate the new program does not help (it is disheartening to see administrators waffling on standard questions of academic eligibility and curricular options). Gen Ed has simply never been fully explained to students, especially those in the class of 2012, whom it will affect most.

To facilitate the transition to Gen Ed, the College should maximize the number of departmental courses that count for Core credit—for example, by further relaxing the requirements for departmental courses and by streamlining the petition process. In the long run, however, it is up to newly appointed Dean Evelynn M. Hammonds and the Task Force on General Education to give Gen Ed a coherent education philosophy and a tenable organization.

While the Gen Ed program suffered from a lack of publicity, Harvard’s new financial aid initiative was showered with media attention. And for good reason: The program is a major step forward in eliminating socioeconomic barriers to attending college. The initiative—which limits annual tuition payments to no more than 10 percent of income for families making between $120,000 and $180,000 annually—allows families in that bracket to save several thousand dollars in tuition payments per term. Other aspects of the initiative demonstrate a sensitivity to college life for students receiving financial aid: The elimination of ongoing loans gives debt-free students the freedom to pursue opportunities in less financially profitable sectors, and the decision to stop considering home equity in ability-to-pay calculations prevents families from being penalized for notoriously shaky housing prices. Although the Financial Aid Office must still iron out details regarding which families are eligible for the 10 percent policy (only those with assets “typical for their income levels” receive such aid), the program is laudable overall, and will help cut down some of the remaining fences between privileged and underprivileged.

This commitment to socioeconomic diversity can also be seen in the laudable decision to eliminate the early action option for applicants. Despite fears that Harvard would lose competitive applicants to peer institutions, this year’s record low admit rate of 7.1 percent vindicates the Admissions Office and demonstrates that the institution’s goals of competitiveness and diversity are not mutually exclusive.

Eliminating early action achieves diversity in two ways. First, it makes the process fairer for those students who could not apply early under the previous system because of a lack of money or inadequate college counseling. Second, the extra time in the fall gives admissions officers and athletic coaches the chance to recruit qualified high school students who would not typically apply to Harvard. While opponents of the decision warned that top applicants would be lost to peer institutions, “letters of intent” expressing interest in a student’s candidacy were sent in advance of official admissions—helping to maintain a high yield.

The numbers speak to the success of eliminating Early Action—a record 11 percent of students in the Class of 2012 are of African American descent, while 9.7 percent are Latino, 1.3 percent are Native American, and 18.5 percent are Asian-American. This is truly remarkable, given that this increased diversity does not come at the cost of quality of applicants. We hope that other colleges will follow Harvard’s example, considering how beneficial the elimination of early admissions policies is to high school students and universities alike.

Unfortunately, not all of the best and brightest will have the opportunity to study at Harvard. A month after the March 2007 application deadline, Harvard announced that it would not accept any transfer students for the next two years due to overcrowded housing.

Although the space crunch is a real problem, transfer students are a relatively small part of the student body. Given that 1,308 students competed this year for a mere 40 estimated transfer spots, admitted students could easily be spread across all 12 houses with minimal disturbance. Using temporary or graduate housing, cutting the size of the incoming freshman class, or reopening housing in Massachusetts Hall (which the College plans to do) would be more effective in confronting the housing constraints.

Beyond the actual substance of the decision, its timing and lack of transparency were also troubling. The fact that the announcement was made well after the application deadline seems arbitrary considering how long the housing situation has been stagnating. Although the College will reimburse the application fee, applicants cannot be compensated for the loss of time, energy, or additional fees associated with applying to college. Ultimately, this amounts to a default rejection of some students who might have been among Harvard’s best, undermining the many recent admissions initiatives aimed at attracting the strongest, most diverse, and most interesting classes possible. It discourages those who have made alternate educational decisions—such as attending community college or enrolling in a two-year program. It also creates a discontinuity in the current campus transfer community, leaving new transfers without guidance from those in years past. While it’s too late to change this year’s decision, Harvard should resume the transfer program as soon as possible.

Certainly, the College has made great strides in making higher education more accessible to those entering its freshmen ranks, but that opportunity amounts to little if the administration pays less heed to students once on campus. If students are to enjoy a meaningful collegiate experience, their lives should be enriched not only by a intellectually coherent curriculum, but also by a student body so diverse as to include those entering from other universities.

Read more in Opinion

Five Reasons for Reason and Faith