The gods must be an ironic bunch. When I visited Mumbai, India, this June, the air was thick with humidity and heavy monsoon rains flooded the crowded streets. Yet even in my grandparents’ flat in the upscale suburb of Bandra—home to Bollywood’s glamorous film stars—low water pressure in the public pipeline meant that the plumbing system worked only two or three hours a day, often in the middle of the night. My grandparents have made do for years by adapting their cooking habits and keeping a bucket of water handy for washing and the toilet. To my Western sensibilities, however, the eccentricities of the overburdened distribution system were simply frustrating.

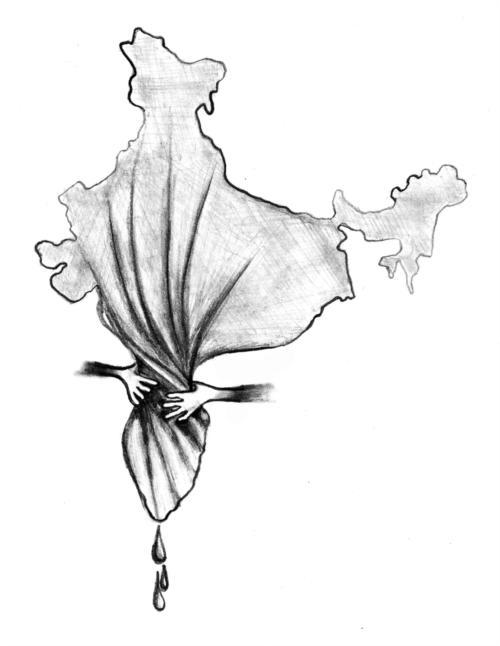

But India’s water woes extend far deeper than mere inconvenience. An estimated 700 million Indians, roughly two-thirds of the population, do not have access to adequate sanitation. Over two million children, especially those in poverty-stricken areas where water is highly contaminated or inaccessible, die every year for want of clean water. Both the fickle faucets of India’s suburbs and the crisis conditions of its poorer areas stem from the same problematic root: that even in the presence of opportunity and emergency, the Indian government has failed to address the national shortage of clean water.

Much of the blame lies with India’s poorly managed central distribution system, a relic of British colonial rule. Because the government fails at providing a 24-hour water supply even in its capital New Delhi, most Indians obtain their water through other means like tube-wells or groundwater pumps. But even these rudimentary sources have been nearly exhausted. A 2005 World Bank report warned that if the government maintains its current policies, in 20 years the country will face a water crisis with violent regional clashes over the precious resource.

Perhaps the most ominous aspect of this shortage is the remoteness of its relief. Thanks to a rapidly growing population, the demand for water is expected to double by 2050. Climate change will also have a long-term effect on the amount of glacial water supplying India’s rivers, which are the source of water for many households.

The Indian government is faced with a number of ways to quench the creeping threat of thirst. The country’s deficient plumbing system, the source of many of its problems, demands a massive overhaul, but the employment of simple techniques to capture rain over just one to two percent of the land would provide as many as 100 liters of water per person a day—much more than the 2.5 liters needed. Groundwater wells contaminated with bacteria from raw sewage, pesticides, and iron could be also be purified using more advanced technology.

But these measures won’t come cheap or easy. Environmental initiatives have never been popular with either the Indian government or its taxpaying citizens, and what millions have been spent seem to have accomplished relatively little. Even with the growing influx of cash from emigrants in the West, the cost and scale of the effort will be formidable.

It is imperative that India take immediate action, even as the lack of water may appear to many as more of a nuisance than a matter of necessity. India’s want for water is growing urgently, and solutions can neither be delayed by apathy nor mired in red tape. Better to plug a trickle now than to confront a cascade later.

Jessica A. Sequeira ’11, a Crimson editorial comper, lives in Canaday Hall.

Read more in Opinion

Five Reasons for Reason and Faith