Quincy Jones’ numbers boggle the mind. He has scored 34 movies and produced or played on 221 albums, including 57 solo projects. He produced the number-one selling album of all time, Thriller, and has 76 Grammy nominations—the most ever for a single artist—with 26 wins. He was nominated for the Oscars seven times, the Golden Globes thrice and the Emmy Award four times, with one win.

But the list continues. Jones has received the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, along with an astonishing 23 other humanitarian awards. He’s received everything from the key to the city of Indianapolis, Indiana to that of Paris, France.

No numbers, however, can describe the power and presence of this living legend when he speaks in the flesh. Fortunately, many students at Harvard had this extraordinary opportunity last week, when the Office for the Arts (OFA) brought Jones to campus as the newest participant of the Kayden Visiting Artist Program. Jones’ connection to Harvard is extensive—he received an honorary degree from Harvard in 1997, the same year his daughter, Rashida, graduated from the College. Jones also persuaded AOL Time Warner to endow the Quincy Jones Professor of African-American Music chair in Harvard’s African and African American studies department. Ingrid Monson, the professor of the popular Core course Literature and Arts B-82, Sayin’ Something: Jazz as Sound, Sensibility, and Social Dialogue, currently occupies the seat.

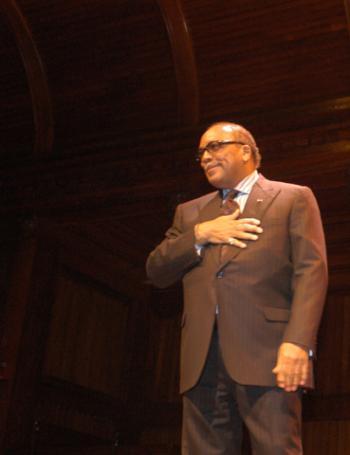

Jones was at Harvard for three nights last week, and he spent his time shuttling between a meeting with campus musicians, having lunch with members of the Harvard arts community and discussing his movies at the Brattle Theater with Assistant Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies and of English and American Literature and Language J.D. Connor ’92, who is also a Crimson editor. The finale came last Thursday night—an extended talk with W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Humanities Henry Louis Gates, Jr. at Sanders Theatre.

The sold-out event at Sanders was a hot ticket among students and local fans, who clamored to see the living legend speak.

“At first, when I heard he was coming I thought I wouldn’t be able to get tickets, ’cause, I mean, he’s a legend. I think between me and my family, [we] have most or all of his albums,” said Dominique C. Deleon ’04, who was able to secure a coveted ticket to the event. “Part of what makes him a legend is his ability to relate to so many different types of people.”

At every event Gates’ seemingly effusive declaration that Jones’ “powers of persuasion are legendary and considerable” is quickly revealed to be an understatement.

Jones’ persuasive powers derive from his charisma and the history that his impressive list of accomplishments brings. As Oprah put it in a clip from a documentary shown at the Sanders Theatre event, “Quincy Jones on a bad day does more than most people do in a lifetime.”

Jones’ rhetorical style is in refreshing contrast to the seemingly canned speeches politicians rehash so often. Watching Jones respond to the questions of fans and interviewers gives the impression that he answers exactly as he believes. Jones’ unique personality gives his comments, which might otherwise get dismissed as clichéd platitudes, the ring of truth.

When asked about Kazaa and other file-sharing programs, he responded simply that, “You have to figure out what’s fair.” Though an obvious oversimplification of the controversy, Jones’ response made it seem reasonable to reconsider the possibility that there is an attainable, fair and final agreement.

In another session, Jones said of the file-sharing services that, “I’ve been in the business 53 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this; but it’s God trying to tell us something.” The key, he said, is that, “nothing lasts, you have to keep going.” A large part of Jones’ success, he realizes, is that “I’ve been open to change.”

Jones implicitly contrasted himself with other artists and businessmen in the music industry. He said, “You can know anyone’s age, creatively I mean, by observing the degree of pain they exhibit when shown something new.” Jones, on the other hand, knows that when new technologies appear, “You have to understand it so you can use it, and it doesn’t use you.”

Examples of Jones’ simple but wise philosophy were evident throughout his talk. He said he decided to understand the business side of the music industry because, “you figure out what you have to do. I saw Basie and Duke pay a lot of dues. At some point you say, I don’t want to be controlled by those considerations.”

Much of Jones’ speech was also quite spiritual. When asked if he is still impressed meeting famous or important people after leading such an impressive life, Jones responded that, “I get impressed with the humanity of a person.”

Jones reiterated the theme of integrity, particularly with regard to questions about the Hip-Hop world. He feels that all artists “are just vehicles for God to come through, and when you only talk about the Benjamins, God will not be on your side.” He had a similar answer to people looking for keys to their own artistic growth. “As Coltrane said, ‘It’s all out there.’ You just have to have the divinity to be able to claim it,” Jones said.

Read more in Arts

Why Do I Keep Super Sizing Me?