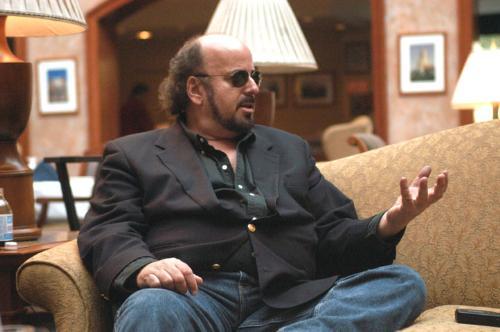

Most of the time when a nervous college student interviews a celebrity, especially a rather notorious one, the pen-twirling, stammering twenty-something is subjected to a lot of blank stares, subtle glances at the nearest clock and terse, rehearsed responses. My most recent experience, with the famed indie bad-boy writer/director James Toback ’66, was decidedly against the norm. Of course, anyone versed in Toback’s impressive body of work, which includes the recently released con-game drama, When Will I Be Loved, knows that he is, too. Before I could lay down one of my admittedly redundant inquiries, Toback drilled me on my own career goals, my life in art and my experience at Harvard.

I told him I was interested in possibly engaging in film criticism for a career, as well as theater, journalism, teaching—all the stock fields for an indecisive college senior. But when I told him I had long entertained the idea of being a filmmaker, he asked, “Do you have a lot of stories in your soul?” The only way I knew to respond was to awkwardly laugh and say, “Sure.”

I’m not often asked that question, and certainly not by a relative stranger. Toback had revealed with his pointed inquiry that if he cared whether or not I had stories in my soul, he must have a few lurking around in his, a fact that’s further reflected in his work, for better or worse. We went on to chat for a solid two hours, riffing on his career in cinema, his views on Hollywood and his personal life, with plenty of comi-tragic anecdotes thrown in the mix.

Stirring Up Controversy

Though Toback’s tangential side-tracking is often hilarious and ironic (consider one true story he related in which famed producer Don Simpson promised Toback to fund his 2001 film Harvard Man minutes before he died of a heart attack), his clear fascination with human beings, myself included, and the way they survive tragedy and day-to-day life is what makes him truly unique. He is often called self-absorbed in relation to his work, and perhaps some truth lies in that statement. But there’s no denying that his preoccupation with human emotion and the ambiguities of what motivates it is the driving force of his work.

“Ultimately you’re writing and directing movies for yourself and for the future,” he says. “You can’t admit that to the people financing them, but basically if you don’t have those two things in mind, you’re not ever really going to be serious about your work. If all you’re worried about is pleasing other people, you’re not going to have any call left at all.” Plus, Toback is used to labels pinned on him by his many passionate critical detractors and supporters over his thirty-year span as a major American writer/director—loquacious, honest, blunt, in-your-face, compulsive, lecherous. But one thing is absolutely certain: Be it through his films or his intense personality, he always keeps things interesting. His new film, When Will I Be Loved, is no exception, showcasing many of the aesthetic and thematic traits that have made his films stand out and have perhaps given him the largely undeserved reputation as a “wild child” of independent cinema.

When Will I Be Loved is a post-feminist, post-noir con tale about a beautiful and wealthy young woman named Vera (Neve Campbell), who is trapped between the lecherous and dishonest motivations of two men who lack the emotional ability to understand her needs. The film is framed by Toback’s exploration of this narrative within the context of Vera’s rampant sexuality and her search for self-discovery. Toback mixes hip-hop with Beethoven, steadicam control with voyeuristic video footage, and he strikes an unlikely balance between conventional melodrama and episodic airiness. Like many of his films, When Will I Be Loved features copious sex, nudity and dialogue that feels simultaneously spontaneous and weirdly controlled.

The sexual aspect of the film is something that, unsurprisingly, has made many critics attack the film as exploitative, with some even calling it misogynistic in its unabashed portrayal of Vera’s numerous sexual exploits that lie at the heart of what Toback calls her “desire for self-discovery.”

It is perhaps worthy to note that attacks on Toback as a misogynist are often wrapped up in the copious press on his personal life. A popular gossip magazine in the ’80s called Spy printed a sensationalist chronicle of Toback’s attempted sexual exploits over a short time period. A four-page foldout chart in the magazine detailed whom he hit on and how he worked his magic. His compulsive girl-chasing behavior, his admitted gambling addiction and, above all, his blunt comments about people he dislikes in the industry have made many critics cast off his films on a personal level.

Driving Characters to the Brink

Campbell bares all in the film. We see her masturbating in the shower, cruising numerous men while on a walk with a sketchy Columbia professor (played by Toback himself), having sex with her boyfriend and videotaping a charged encounter with a female lover. To Toback, the sexual energy of the character is necessary to establish her as a woman at a stage in her life in which her sexual proclivities are pushed to the forefront of her developing emotional maturity. At times the film plays like a kind of realist La Dolce Vita, showing a woman so lax and free of worldly commitment that her desire for pleasure becomes the core of her identity.

Toback explained that he made the character extremely wealthy because he wanted to make it explicit for the audience as to how she is able to live so care-free in her personal life.

“If you’re going to get to the bottom of a character, letting the character get free of financial need is one of the ways of doing it,” he says. “I’m kind of fascinated by that one-tenth of one percent of humanity. I think the inability to use the absorption of time as an excuse for not delving into things emotionally and personally that you would otherwise be delving into often keeps people from levels of self-discovery that they might otherwise achieve.”

Toback frankly discussed these themes in his films with the kind of voracity that details his obsession with his characters and the troubling decisions he forces them to make. “I think it’s only interesting when you find people stressed out, pushed to their limits, exposed by adversity,” he says. “If you’re making a serious movie, deal with death, deal with madness, deal with the extremes of human possibility. That’s when people reveal themselves, that’s what’s fascinating to me.”

A prominent feature of his films is that he places his characters in situations that require almost otherworldly instincts. What perhaps gives his films their reputation as being “edgy” is his consistent penchant for placing his characters in a kind of hyper-real universe in which they face extreme hardship and sharp transition around every turn. He explains that this is the best way to uncover the strange behavioral truths that make such situations survivable.

“You don’t get to any truth by softening things, by trying to push it into the middle,” he says. “You get to the truths of people by pushing them out to the edges of human behavior and human emotion. I’m trying to create circumstances where they’re forced into radical action and self-revelation.”

Pushing the Envelope

Controversy, or at the very least disagreement, among the critical community, is a key element of Toback’s career. His directorial debut, 1978’s Fingers, was, as Toback describes it, “defiled, defamed and rejected except by a handful.” That “handful,” however, included famed critics David Thompson and Pauline Kael, and the film is now regarded as an American cinema classic.

But even though Toback’s films always have their loud supporters, the most likely reason for his remaining a proficient and functional artist amidst storms of critical attacks is the simple fact that he doesn’t let it get to him.

“I would certainly feel that if I made a movie that everybody liked there was some failure of ambition in the movie,” he says. “And I would probably feel if I made a movie that everybody disliked that I was in some weird place in relation to the current world.”

What is perhaps most striking about Toback’s cinematic repertoire is that he has always stayed on the fringes of commercial cinema. Though he describes his relationship with Hollywood as a “mutual resistance,” the closest he has come to personal involvement in a major Hollywood production in the last fifteen years was writing the screenplay for Barry Levinson’s Bugsy.

But Toback’s aversion to studio filmmaking could hardly be described as ideological. His films typically take on issues that are not commonly approached in contemporary mainstream filmmaking.

“Dealing with the dread, with the void, with madness. Those are reasons to make movies,” he says. “Without those reasons, making movies would be no more appealing to me than doing jingles for some ad agency. It isn’t that making movies is inherently an interesting occupation.”

Starting his cinematic work in the 1970s during a period of American cinema in which experimentation was highly valued (primarily due to the steady economic breakdown of Hollywood in the ’50s and ’60s), Toback sees the Hollywood of today as a kind of dead space in which filmmakers are always pushed to “shoot for the middle.” He sees dealing honestly with adverse topics a near impossibility in the mainstream cinematic landscape.

Says Toback, “The system right now as it exists is so filled with checks and balances, with restraints and cautions, with marketing strategies that involve shaving off the extremes so that you can hit some mythical common denominator in the middle of America, that it’s almost impossible for someone who has an agenda like my own to function fruitfully within it.”

Toback may seem overzealous in his denouncement of the tenets of Hollywood cinema, but, nonetheless, it’s difficult to deny that very few mainstream directors could pull off not only the sexual content, but also some of the visual and especially sonic experimentation of When Will I Be Loved in a studio setting. This is to say nothing of his earlier films, particularly considering that his latest is actually more digestible than more intense offerings like 1999’s racially charged drama Black and White.

Toback’s consistent fascination with the darkness inherent in human personality and the way that sex can be a tool for self-discovery at the same time that it can inspire madness keep Toback tucked safely away from the norm.

“I’m unseducable by that idea of film as a way of getting rich and famous,” he says. “What then is the point of making movies? To me it has always been to discover fascinating characters and how they behave under extreme circumstances. To get to the bottom of human personality, experiment musically, experiment with image, try things that are ambitious and new.”

Toback’s next project will likely be his “long overdue” semi-autobiography, a project he has been writing for years, even before 2002’s Harvard Man even shot. The coming months will also see the release of the Bobby Darin biopic Beyond the Sea, directed by Kevin Spacey and cowritten by Toback. Regardless of what he chooses to do next, his future projects will likely be as thematically ambitious and daring unless he makes a serious change in genre.

As he puts it, “You can’t do a serious movie in the corporate system now unless you have re-incarnation or some science fiction gimmick.” The message is clear: don’t look for James Toback to be selling out any time soon.

—Staff writer Clint J. Froehlich can be reached at froehlic@fas.harvard.edu.