I wonder if Dean of the College Rakesh Khurana likes “Dead Poets Society.”

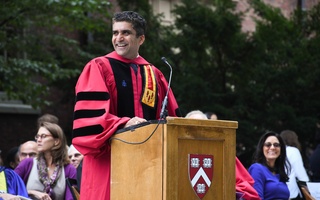

At my Convocation three long years ago, Dean Khurana presented a dichotomy that has overshadowed my college experience. Standing before us on that sweaty day, Khurana forecast that we could follow one of two paths to graduation: One would be “transactional,” in which we would chase material goals, taking easy classes and residing within a homogenous circle of friends, on our way to comfortably receiving our Harvard degree with minimal contemplation. The other was “transformational,” in which we would challenge ourselves in our coursework, in diverse extracurriculars, and in our intellectual discourse with our classmates, leading us to some sort of radically enlightened and non-materialistic perspective on life. For me, the speech evoked a group of inspired prep school boys standing on desks reciting Walt Whitman, the Dead Poets Society valiantly fighting back against the impending concrete reality of the real world. Could such an idealistic college experience really exist?

I have always thought of transformation as an admirable goal, but I have learned that, whether I like it or not, there are many transactional elements that are inseparable from a Harvard education. Matriculating Harvard students generally want to be successful in some way, which requires building up an impressive resume, making connections with recommenders, and seeking help from peers on that problem set you waited until 2 a.m. the night before the deadline to get started on. I have learned, in short, that a transformative, fulfilling college experience need not, and should not, come at the expense of giving up my worldly ambitions and thus my transactional actions.

That being said, Harvard undoubtedly has a problem with an overwhelmingly transactional culture. As each semester unfolds, grabbing meals with friends transitions to “grabbing meals with friends,” changing from a joyful reality to a meretricious promise uttered in passing on Mount Auburn St. Walks along the Charles or impromptu ultimate frisbee games are traded in for the daily grind of problem sets and job recruiting. Planning trips to Boston with the blocking group or watching basketball with the roommates proves increasingly impossible to schedule between club activities and midterm studying. The fast pace of life, driven even faster by our near-ubiquitous competitive natures, leaves many of us feeling lonely, depressed, and even suicidal at times, as we scurry from our 4 o’clocks to our 5 o’clocks to our 6 o’clocks, hemmed in by our regimented lives. This transactional culture is rarely desired, and most Harvard students actively fight back against it. Yet this culture has proved intractable, despite most of our best intentions.

Harvard has never been, and will never be, only about group readings of Chaucer or wildly different people sharing life stories into the wee hours of the night. As long as Harvard is one of the best schools in the world, the truth is that students will fill a good portion of their time with productive, even transactional, activities. But the transformational moments matter, too. They challenge our perspectives. They teach us how to connect with others and engage with the world. They help us become good people. They are the memories that will remain with us when we are old and shriveled. So how can we simultaneously pursue our legitimate material aspirations while also living fulfilled lives?

The first thing we can do is recognize that transactional and transformational experiences are not arch-nemeses, locked in some sort of Manichaean struggle between good and evil. Padding your resume or attending recruiting events (even for the oft-derided consulting jobs) does not make you a bad person, just as whimsically taking that Theater, Dance, and Media class as a STEM concentrator does not make you a good person. Pretending like we must choose between the noble life of transformation or the sullied path of transaction puts impossible expectations on us to shun our career aspirations all the while being inundated by a sea of opportunity. Instead, it is not as much about the fact that we are sometimes transactional, because we all are. Instead, it is about how and why we do those transactional things we choose.

When I took my first Computer Science 50 midterm my freshman fall, I was so nervous that I didn’t even put my name on the test. After leaving the lecture hall, I remember bawling before calling my mom to tell her that I was going to fail the class (I didn’t. P.S.A., freshmen: Curves exist.). In that moment, I did not have some sort of epiphany that “there is no such thing as failure.” In fact, I had failed myself, and that was precisely why it had hurt. But, in the aftermath of the course (which continued to be a bloodbath for me, mind you), I realized that that particular failure was not one that I really cared about. In fact, getting a good grade in CS50 was not a transactional experience that I really needed; no one for the rest of my life has asked me what my grade was in that class, and that midterm, which at the time felt like a Super Bowl loss, has faded into an obscure memory.

Before, I had thought that I needed to do transactional things for the sake of the transaction. But, with time, I have learned that transactions feel more fulfilling when they are the means to an end that actually makes me happy. With that mindset, applying to jobs and research grants still feels like a chore, but a trivial one, because the jobs and fellowships I have applied to are things that would truly give me satisfaction. And by being targeted in my transactional actions, I have been able to make more time for the transformational aspects of my life, from literally debating the meaning of life with my roommates until the weekday dawn to sneaking out with a friend to camp on the Harvard football field on an autumn night.

Harvard presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the world’s smartest people to pursue the world’s most ambitious aspirations, but with that status comes a deluge of stress. However, that stress doesn’t have to come with loneliness or ennui. By learning from the positive experiences of our peers, Harvard students can help transform the culture here to make it more amenable to self-pride and companionship, and we can learn to better balance our ambitions with our happiness.

Reed T. Shafer-Ray ’18 is a Social Studies concentrator in Quincy House. Their column appears on alternate Thursdays.

Read more in Opinion

We Are More Than “Narcos”Recommended Articles

-

Spring Break Postcard: Food in Ma BellyMy roommate decided to visit me at home in Philadelphia. It was frigid, and every day we ate sandwiches. My goal: that he would leave with a fuller stomach, significantly closer to heart disease, his face slick with oil.

-

Southern ComfortOf course, it’s not just the coastal elites that buy into the Manichaean narrative. To Mike Huckabee, this country is divided into Bubbaville and Bubbleville, with the homier residents of Bubbaville superior to their snobbish, coastal counterparts. Neither narrative is true. Behind these simplified labels and tropes are identical people, from which no group is better than any other.

-

Taking Time Off: In Search of a Messy PathThe Harvard bubble has obfuscating powers.

-

When Harvard Jumps the SharkIf we so focus on Harvard the home to the extent that we forget about Harvard the educational transaction, we risk not only inviting administrative intrusions into students’ social lives, but also, perhaps more sinisterly, adopting expectations that put emotional or social comfort before intellectual growth.

-

Transactions and Transformations

Transactions and Transformations