As I sat in the audience of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee’s Policy Conference two weekends ago, I could have sworn I was at a Megillah service. People were making a lot of noise and railing against a Persian leader who wanted to annihilate the Jews.

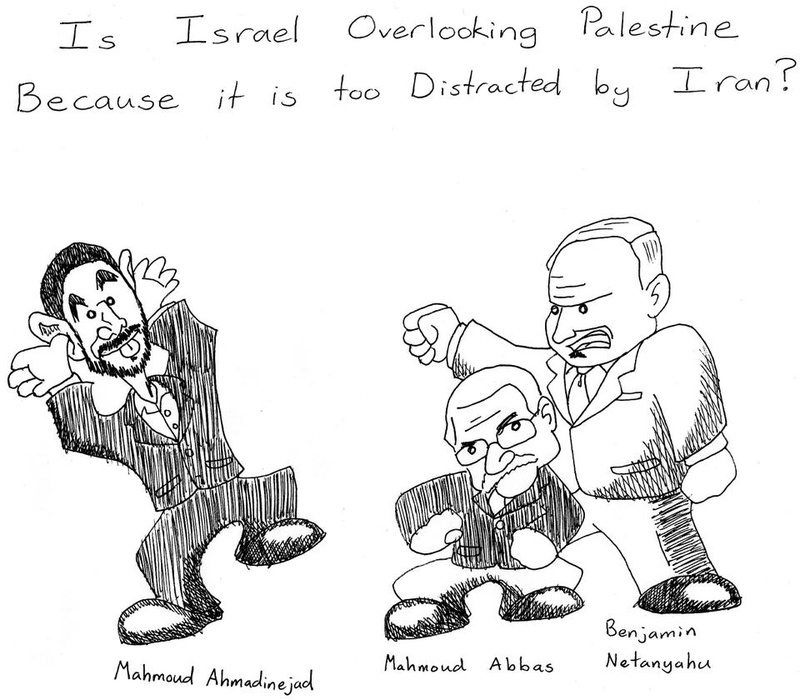

The Islamic Republic claims it wants nuclear capacity for peaceful purposes. That’s a highly dubious proposition. But so is the notion that Iran would drop an atomic bomb on Tel Aviv. Even if President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is a modern-day Haman, he lacks the power to realize his vision. Like all Iranian presidents, he is a glorified functionary, with real authority invested in Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Despite essentialist, facile chatter about the mullahs' “culture of death,” Khamenei is a realist. He knows Iran will be “obliterated” if it perpetrates a second Holocaust. Instead, the Islamic Republic seeks to challenge Israel’s military superiority and counterbalance the American-Saudi axis. Those aims menace the geopolitical interests of the U.S. and the Jewish state, and the two countries have responded with appropriate and devastatingly effective sabotage campaigns.

Israel has long pondered a strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, and tried to enlist American backing during the Bush years. There are good reasons to oppose such an action—many Israelis, including President Shimon Peres, are against it. If the program were not destroyed, it might resume further underground. Even worse, an attack could also be the reveille of regional war.

If I dispute AIPAC’s analysis of the Iran affair, I also take issue with the false narrative of Jewish powerlessness to which such a focus contributes. At the conference’s plenaries, almost every speaker invoked the Holocaust, as if to link the Shoah and the present moment. AIPAC President Michael Kassen spoke of “danger,” “threats,” and “turmoil” facing Israel, the word “extermination” hanging in the air. Even the aesthetics made one feel small and impotent, incongruous with an event widely seen as a showcase of the Jewish community’s "power."

What was conspicuously absent from Kassen’s address—he mentioned Syria, Egypt, Jordan, and yes, Iran—was any discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Indeed, throughout the confab, there was spare reference made to the occupation or the peace process. Most speeches evinced general support for Israel yet did not detail who that support was directed against. The emphasis on issues of victimhood rather than agency was deliberate, for agency implies responsibility, and responsibility points to Israel’s untenable occupation of the West Bank.[NM1]

AIPAC’s political theater contrasted starkly with what I saw in the movie theaters upon my return to Cambridge. The first film was “The Gatekeepers,” an examination of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank through the lens of six former heads of the Jewish state’s internal security service, the Shin Bet. In frank interviews, the ex-chiefs admit to ordering extralegal killings, overseeing torture of prisoners, and carrying out policies that made Palestinian life miserable

The second was “5 Broken Cameras,” screened by the Palestine Solidarity Committee as part of “Israeli Apartheid” Week. (I think the apartheid label is a canard, but Joshua B. Lipson and Ariel Rubin and Ariella Rotenberg have already done the yeoman’s work of explaining why that is.) Filmed by Palestinian farmer Emad Burnat, the documentary chronicles the construction of the West Bank separation barrier, which threatens to cut off the townspeople of Bil’in from their farmland. In response, the villagers stage non-violent protests against the wall, and through their campaign and Burnat’s camera we catch glimpses of Israel’s darker side—reckless, overly aggressive soldiers; violent, vandalizing settlers; occupation-traumatized children.

Coming from different sides of the fence, “The Gatekeepers” and “5 Broken Cameras” happen upon the same message. That guns and walls are no substitute for a comprehensive West Bank policy and peace process. And that the occupation hurts everyone it touches, denying Palestinians basic rights like freedom of movement and imperiling Israel’s status as a Jewish democracy.

AIPAC and the Israeli government have direct agency in this matter. Unfortunately, they have missed the most important part of the Purim story: Esther’s courage.

Daniel J. Solomon ’16 is a Crimson editorial writer in Matthews Hall. His column appears on alternate Tuesdays. Follow him on Twitter @danieljsolomon.

Read more in Opinion

Changing the Paradigm